Myth of Mujib: Isn’t this the high time to get a reality check?

Myth of Mujib

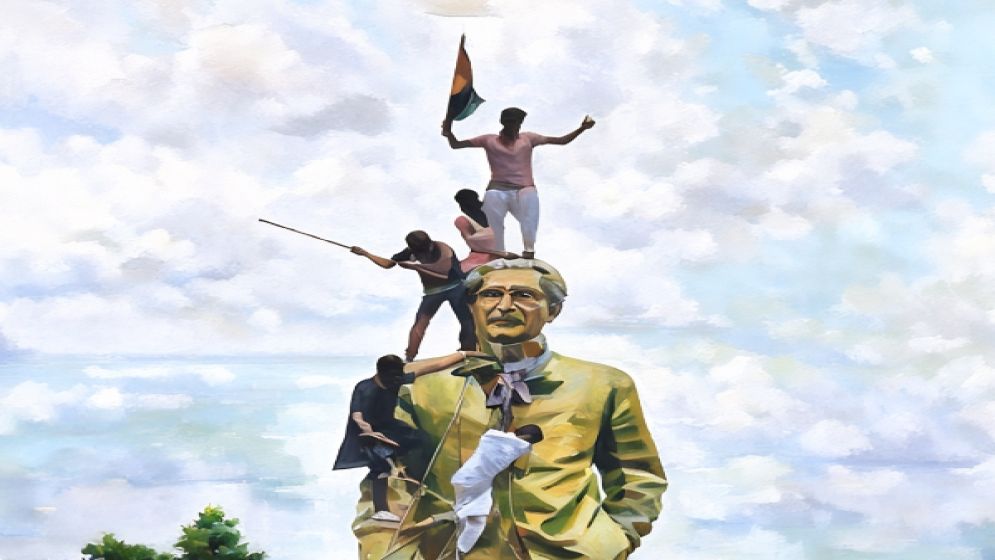

In the wake of Sheikh Hasina's downfall during a student-led uprising, enraged crowds targeted buildings they perceived as emblematic of her 15-year authoritarian regime.

Among these was the historic home of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman– Hasina’s father–in Dhanmondi-32, now a museum.

Actor Rokeya Prachi's much publicized visit to the burned museum to express her grief raises concerns about the enduring reverence for Sheikh Mujib in Bangladesh.

Her public mourning for a damaged building seemed to disregard the profound suffering of families who lost loved ones to the Hasina regime's violence - a regime that had ironically spent years glorifying Mujib's legacy with public funds.

That evening, Prachi was photographed by

a small square unit near Dhanmondi 32, her professional instincts on full

display, while thousands of victims of the Hasina regime suffered in nearby

hospitals.

Her apparent sorrow for Mujib seemed alarmingly disconnected from the widespread anguish caused by Sheikh Hasina, who appears to believe her family has a divine claim to the nation.

The deposed Hasina regime's veneration of Sheikh Mujib mirrored the way Kim Jong Un is exalted in North Korea or how Middle Eastern royals are celebrated on their grand birthdays.

For Mujib’s birth anniversary, billboards adorned the country, students in schools saluted his portrait, government documents featured his watermark, and mobile phones eerily played ringtones of his familiar voice in tribute.

It would be misleading to view Hasina's

actions as merely a misuse of power aimed at establishing Sheikh Mujib as the

father of the "race," rather than just the father of the

"nation."

This was, after all, Mujib’s own aspiration, as highlighted by Gavin Young–a writer, traveler, and esteemed foreign correspondent for The Guardian– in his August 17, 1975, piece "Mujib's Muddled Dream" in The Observer.

Lack of objective and unbiased accounts

A significant portion of Bangladeshis genuinely believe in Sheikh Mujib’s infallibility, treating any critique of his politics as heretical.

Young’s depiction of Mujib’s governance

from January 1972 to August 1975 as “egoistic, complacent, and lazy” is largely

disregarded, as if a sense of redemption enveloped him when the Sten gun was

fired in the early hours of August 15, 1975.

It's reasonable to argue that a heroic image of Mujib has persisted due to the lack of an objective and unbiased account of his rule from 1972 to 1975. Examining this period through credible international sources could provide a more accurate and balanced understanding of Mujib's leadership.

On August 16, 1975, The Guardian labeled Mujib's death as "a toppled symbol of corruption and dictatorship." Gavin Young, the writer of the article noted that "Mujib proved a hopeless administrator, what is more, his enormous popularity went to his head; he became egoistic, complacent, and lazy".

Major analysts of Bangladesh at the time

agreed that under Mujib’s leadership, nepotism and corruption became rampant.

Awami League leaders scrambled to exploit the substantial aid that flooded in after independence and because of that many Bangladeshis were left struggling to survive on little more than a handful of leaves.

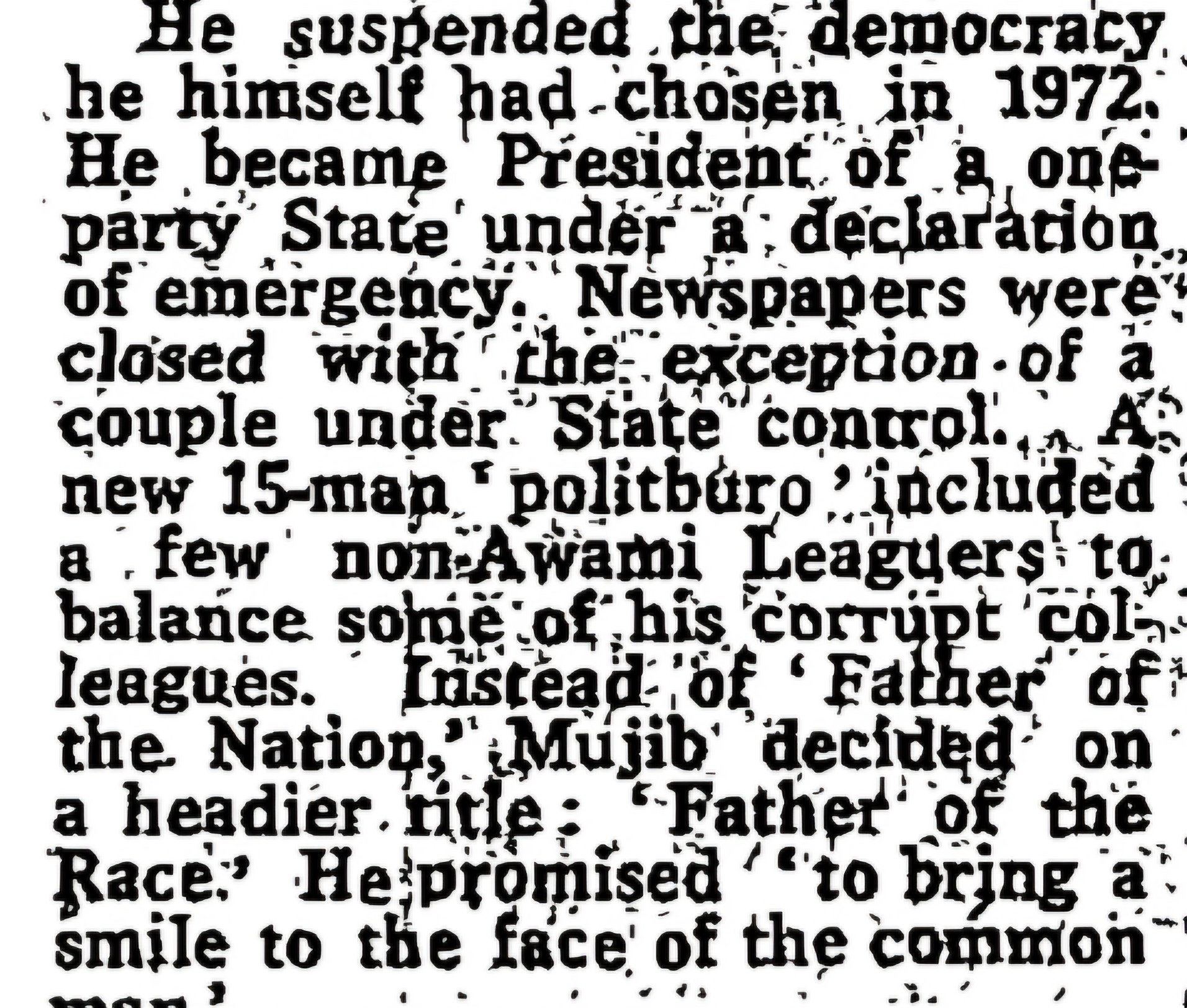

Young described the last days of Mujib as follows: "He (Mujib) suspended the democracy he had chosen in 1972. He became president of a one-party state under a declaration of emergency. Newspapers were closed except for a couple under state control. A new politburo included a few non-Awami Leaguers to balance some of his corrupt colleagues."

Another significant perspective on Sheikh Mujib's rule comes from Timothy Damien Allman, an American author, historian, and journalist.

Allman worked as a freelance foreign

correspondent in Southeast Asia from 1968 to 1971, focusing on investigative

and analytical reporting on the Vietnam War.

On August 18, 1975, he reported from Delhi for The Guardian that "Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's personal history of power in Bangladesh was that of a supreme national hero whose prestige was steadily eroded by corruption, nepotism, incompetence, and coercion."

Following Mujib’s tragic death on August 15, 1975, Martin Woollacott, the foreign correspondent and foreign editor for The Guardian defined Mujib’s ruling style as ‘relaxed to the point of sloth’.

He wrote, "It was typical of Sheikh Mujib's relaxed approach to politics that after suspending democracy, nothing much happened for several months."

Woollacott continued- "Mujib sat in his office like the medieval ruler he psychologically was, laughing and joking with friends and colleagues, telling anecdotes, giving lectures, and dealing with the daily queue of supplicants."

Time for busting the myth

These descriptions will resonate with those of us who, in disbelief, watched how Mujib’s daughter managed her leadership.

She arranged frequent press conferences, which resembled a modern take on a medieval royal court. During these events, uncritical and sycophantic journalists queued to extol her virtues and dared not question the corruption and abuse of power that plagued Bangladesh during her 16-year rule.

The road ahead for Bangladesh is not going to be smooth. Expert NGO administrators with outstanding credentials alone will not suffice unless they confront the myth surrounding Mujib that has affected a segment of the nation unwilling to see him for who he truly was.

Mujib was a national leader who failed to live up to the trust placed in him by the country. He left the nation in a worse state than he inherited it after the bloody war, while ordinary Bangladeshis endured hardship as he spent his time in a West Pakistan cell, puffing on his Erinmore pipe.

—-

Ehtasham Haque is the founder of Bangladesh Solidarity Campaign UK. He was a former Labour councilor