Panic vs. reality: Are food prices in Bangladesh truly skyrocketing?

While social and mainstream media portray Dhaka's essential food prices as skyrocketing, the reality is more nuanced.

It's understandable that recent political upheaval, disruptions in law and order, and devastating floods have fueled concerns about food security and price hikes.

Adding to this anxiety are widespread allegations of market manipulation by "syndicates."

However, data indicates that, with the exception of red lentils, current prices for most essential food items remain largely consistent with recent trends.

This isn't to dismiss the very real challenges in food production and distribution, but it suggests that the situation may not be as dire as some reports suggest.

These findings have important implications. Policymakers must avoid knee-jerk reactions driven by panic and focus on evidence-based solutions.

Simultaneously, pro-democracy advocates should actively combat misinformation that could unnecessarily exacerbate fears and instability.

A clear-eyed understanding of the situation is crucial for both effective governance and maintaining public trust.

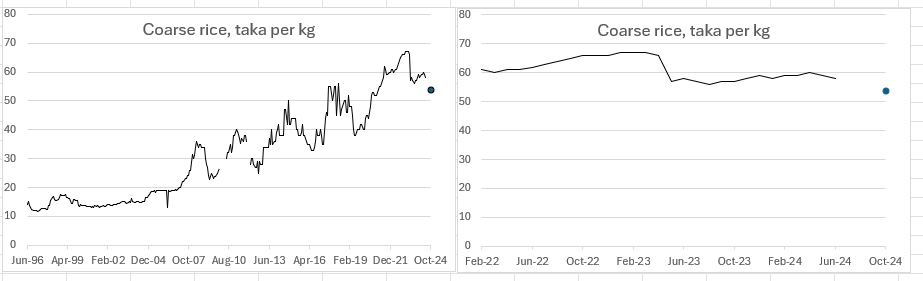

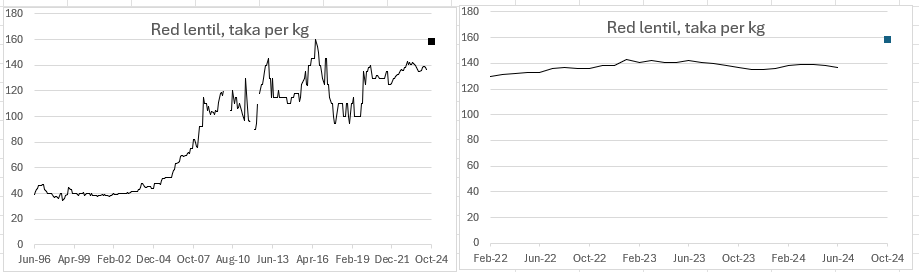

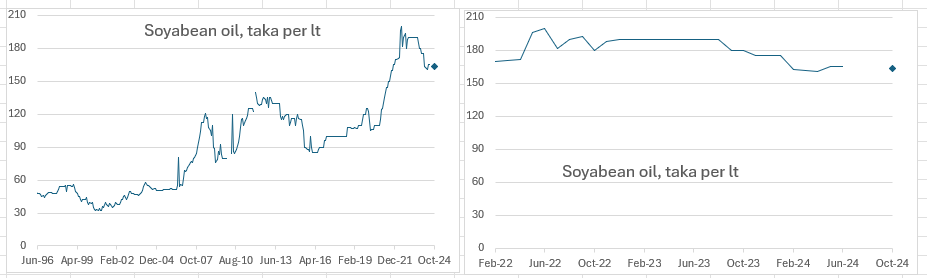

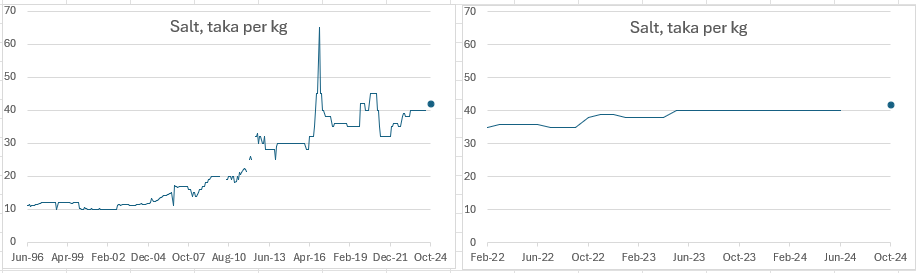

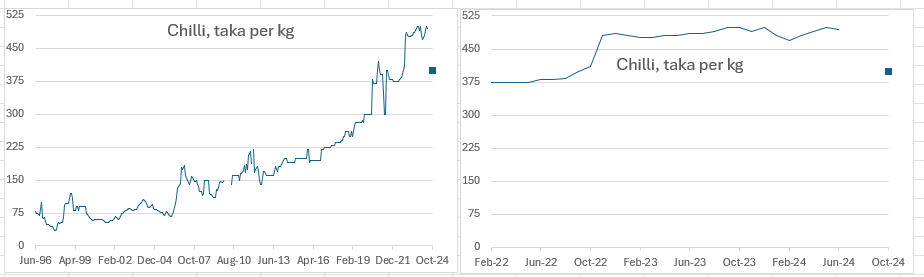

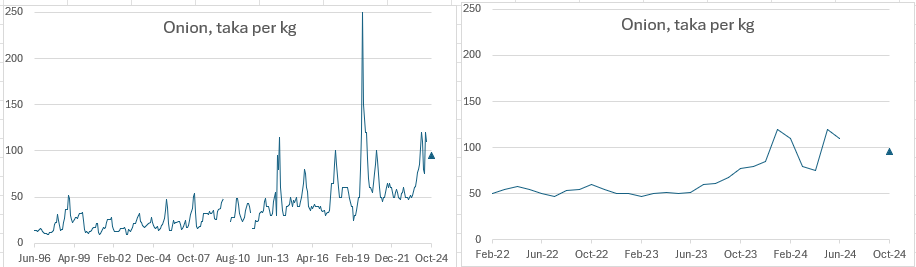

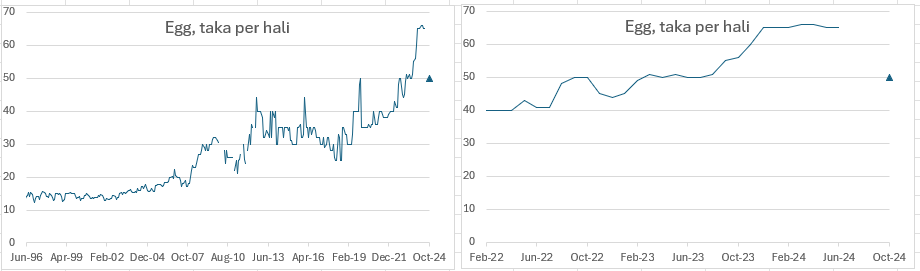

Let’s first examine the data and charts. I’ve plotted the monthly average prices since October 1996 (left panel) and February 2022 (right panel) for the following items: coarse rice, red lentils, soybean oil, salt, chilies, onions, and eggs.

All prices are from Dhaka, and the time series comes from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, ending in June 2024. It’s worth noting that if the BBS fabricated data during the previous regime, historic prices in recent years might be understated, meaning they could have been higher.

Since June, the BBS hasn’t released any new data, for obvious reasons! I’ve gathered the latest prices using Google and various online grocery stores.

Since online retailers often charge more than local markets, such as those in Nakhalpara, the October figures might be somewhat inflated, indicating that current prices could be lower.

To account for potential biases, I’ve represented the October data with a thick marker instead of a dot; this approach conveys a range rather than precise values.

These charts suggest that the current prices in Dhaka are not particularly out of line with recent history. In fact, for some items, prices are lower than they were during Hasina’s time in office!

Certainly, these charts indicate that the

prices of these items are significantly higher than they were a few years ago.

However, this trend reflects the macroeconomic mismanagement of the Hasina

regime, rather than recent events.

Additionally, prices may have risen in September before experiencing a recent decline—consider the impact of blockades and floods!

The drop in prices could be attributed to the government reducing import tariffs on certain items, or it might simply be due to increased production entering the market. Regardless of the cause, current prices are not out of line with what they were during Hasina’s tenure.

As for other items like potatoes, tomatoes, fish, and chicken—there are certainly many additional products we could analyze, but the ones mentioned are essential for a working poor individual in Dhaka.

In summary, there doesn’t appear to be a compelling reason for alarm regarding prices.

What do I mean by "panicking"?

History offers a cautionary tale about misguided attempts to control prices. In 2007, the 1/11 military regime, fueled by accusations against "syndicates" associated with the previous government, launched a crackdown that backfired spectacularly.

Their actions triggered a supply shock, driving prices even higher and ultimately undermining their own rule. Even a seasoned central banker couldn't dissuade them from this disastrous course.

This wasn't an isolated incident. As the late Akbar Ali Khan often observed, targeting supposed market manipulators is a recurring misstep by military rulers.

Today, with similar accusations swirling in the media and public anxiety high, there's a real danger of repeating this mistake.

The current government might feel pressured to intervene in ways that could further disrupt supply chains and exacerbate price increases.

It's crucial to remember that well-intentioned but ill-informed actions can have unintended consequences, potentially leading to greater economic instability.

This isn’t to imply that questionable practices didn’t exist under the previous regime—there may well have been.

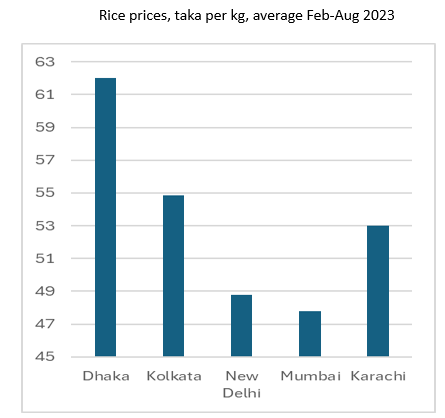

For example, as shown in the chart below (data source: CEIC Asia), a kilogram of rice in Dhaka was often more expensive than in other major subcontinental cities. This could stem from higher production costs, excessive markups by intermediaries, or even the existence of real syndicates. It’s crucial to explore these factors in more depth.

Additionally, it’s very likely that many urban

poor have faced income losses.

Additionally, it’s very likely that many urban

poor have faced income losses.

Nevertheless, these issues are separate from the concerns regarding high prices and syndicates.

—-

J Rahman is an economist and a writer