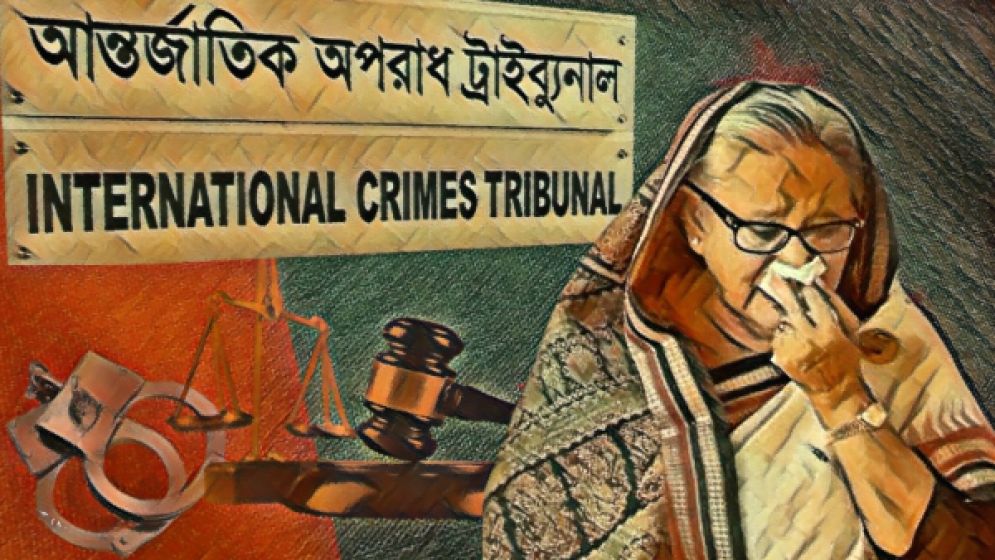

Legal labyrinth: The difficult road to extraditing Sheikh Hasina

Quazi Omar Foysal

Publish: 26 Oct 2024, 04:02 PM

With the International Crimes Tribunals-Bangladesh (ICT-BD) now in session and arrest warrants issued for around 50 individuals, including former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, Bangladesh may seek to extradite those residing abroad, particularly in India.

Reports indicate that several Awami League leaders and former officials are currently having safe refuge in the neighboring country.

Although the ICT-BD can conduct trials in absentia, having the accused present is preferable to maintain credibility.

Chief Prosecutor Tajul Islam has suggested that Bangladesh may request Interpol’s assistance in bringing them back for trial.

Consequently, Bangladesh should actively explore diplomatic and legal avenues for the return of those evading justice.

Extraditing ICT-BD suspects, including Hasina, from India is legally feasible under the 2013 Extradition Treaty, amended in 2016.

While preliminary assessments indicate that Bangladesh's extradition request could meet legal criteria, India may refuse based on specific provisions, including cases involving political offenses or a lack of good faith in the accusations.

It is widely believed that India could invoke the "lack of good faith" clause to deny extradition, potentially shielding individuals accused of war crimes from trial.

Many former Awami League leaders, including Hasina, face serious charges, with reports of harassment at court premises.

India may consider these factors and opt to block the extradition based on them. In this context, international law could provide valuable insights into addressing challenges from Indian authorities.

Complex legal tangles

Although neither India nor Bangladesh has formally ratified the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT), its principles are widely recognized as customary international law and could influence the extradition case for war crimes suspects.

The VCLT offers guidelines for treaty interpretation, which will be essential in evaluating India’s potential arguments for denying extradition under the India-Bangladesh Extradition Treaty.

Specifically, its rules could clarify the "unjust or oppressive" clause that India might invoke.

It is to be noted that the India-Bangladesh Extradition Treaty includes clauses that allow India to refuse extradition under certain conditions.

The principle of "either extradite or prosecute," which applies to serious crimes like torture and is recognized in international human rights conventions, could shape India’s interpretation of these clauses.

This principle may compel India to extradite suspects to Bangladesh or prosecute them under its own laws.

India could block the extradition request by invoking the principle of non-refoulement, which prevents sending individuals to a country where they may face persecution.

However, Bangladesh can counter this by providing "diplomatic assurances" that the suspect's human rights will be upheld during the trial.

For these assurances to be effective, they must be "reliable" and "effectively monitored," requiring Bangladesh to align its legal framework and the proceedings of the International Crimes Tribunal of Bangladesh (ICT-BD) with international human rights standards.

Given that the trial is already underway, Bangladesh must act swiftly to ensure compliance with these standards to facilitate extradition.

The checkered history of Bangladesh’s

ICT tribunal

Bangladesh is also under pressure to reform its International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) before India will consider extraditing a suspect wanted for war crimes.

The current ICT law has faced criticism from human rights organizations and the United Nations for not meeting international standards.

The government is reportedly working on amending the ICT Act to address these issues, but these reforms should be finalized before an extradition request is made.

However, with no formal dispute resolution mechanism in the India-Bangladesh Extradition Treaty, successful extradition will likely hinge on diplomatic negotiations and Bangladesh’s commitment to human rights.

India’s potential refusal to extradite a suspect wanted for war crimes meanwhile could violate victims’ rights to justice.

While no international court can compel action, India's obligations under international law, including the principle of "good faith" in treaty interpretation, may necessitate cooperation.

Reports from the UN human rights office highlight credible allegations of non-political crimes committed by the suspect.

Denying extradition could thus infringe upon victims' rights protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which both countries are parties.

This underscores the complex relationship between international law, human rights, and political factors in extradition cases.

So, if Bangladesh offers adequate guarantees for a fair trial, India's refusal to extradite a war crimes suspect could violate international law and invite repercussions.

By leaning on the "unjust or oppressive" clause in the treaty, India risks breaching its legal obligations, potentially harming its reputation and straining relations with Bangladesh.

Ultimately, India must balance its international legal responsibilities with its aim to maintain positive relations with Bangladesh, and it is anticipated that India will prioritize its relationship with the Bangladeshi people by allowing the suspect to face justice.

—

Quazi Omar Foysal is an international law expert, currently working at American International University-Bangladesh.