The undemocratic trend: Seven charts illustrating the fragile state of democracy in South Asia

This year marks a significant electoral period, with hundreds of millions of potential voters across the three largest South Asian nations, which could have been at the forefront of a historic democratic exercise.

In Bangladesh, the election unfolded as anticipated, with the Monsoon Revolution, rather than the disputed election of the previous winter, paving the way for a new democratic era.

While initial results in Pakistan were surprising, the outcomes that followed aligned with expectations.

India also saw an unexpected election result, though it may be too early to predict the implications there.

The elections reflect a continuing trend of convergence among these three countries.

For decades, Pakistan and Bangladesh struggled under democratic governance, while India consistently held free and fair elections, with its judiciary, media, and civil society serving as models for its neighbors.

Recently, however, all three countries have been moving away from democratic principles.

According to a widely recognized democracy metric, India's democratic strength has been declining over the past decade, now resembling the weaker democracy of Pakistan, while Bangladesh's democracy has been less robust than its neighbors since 2007.

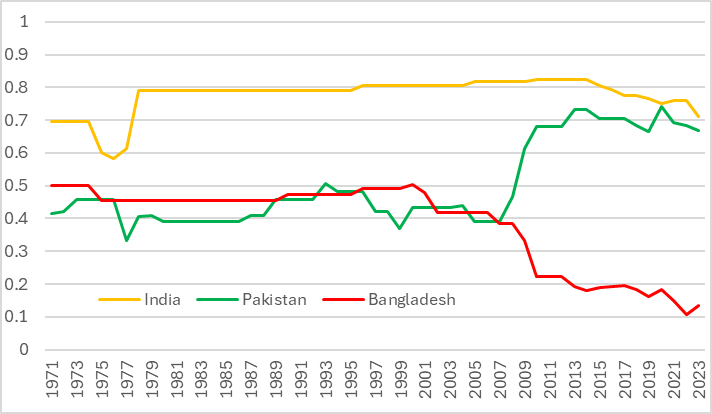

The V-Dem Institute at Sweden’s University of Gothenburg provides indices that assess the relative strength of democracy, scoring from 0 to 1, where scores nearing 1 indicate stronger democratic practices.

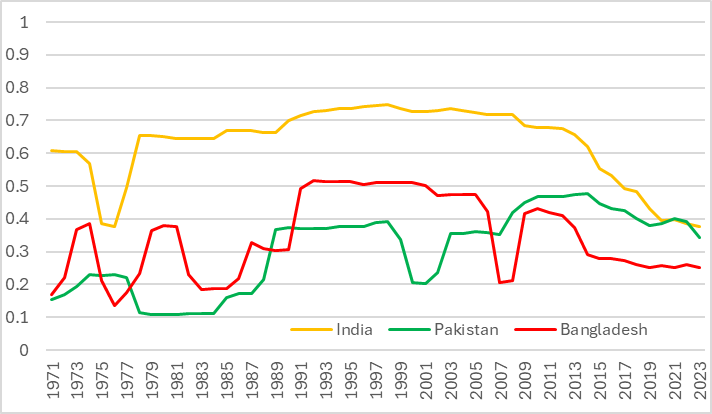

Their 'Electoral Democracy Index' captures the essence of democracy, emphasizing that rulers should be accountable to citizens through free and fair elections.

As shown in Chart 1, Bangladeshi democracy peaked between 1991 and 2006, while India's democratic decline began in 2014.

Their indices extend to 2023 and do not account for the 2024 elections or the Monsoon Revolution. However, the 2014 and 2018 elections are closely linked to the decline of democracy in Bangladesh.

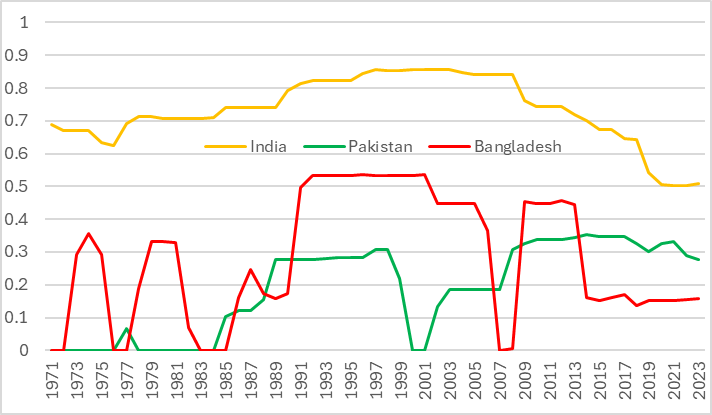

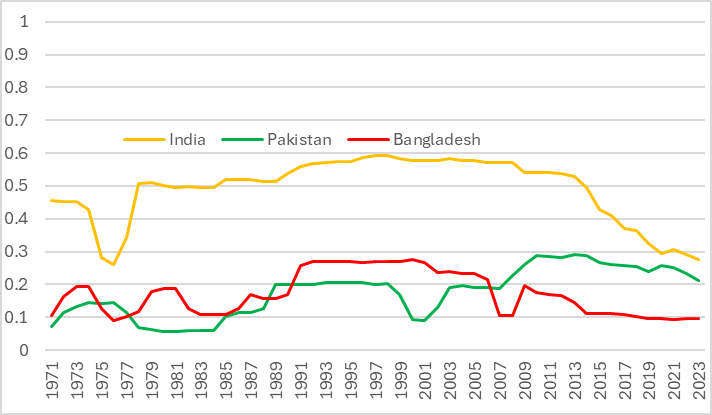

This is reflected in the ‘Clean Elections Index,’ which assesses whether the electoral process is tainted by issues such as registration fraud, systematic irregularities, government intimidation of the opposition, vote buying, and electoral violence.

As shown in Chart 2, aside from periods of military intervention, Bangladesh's election process has never been weaker than it has been since 2014.

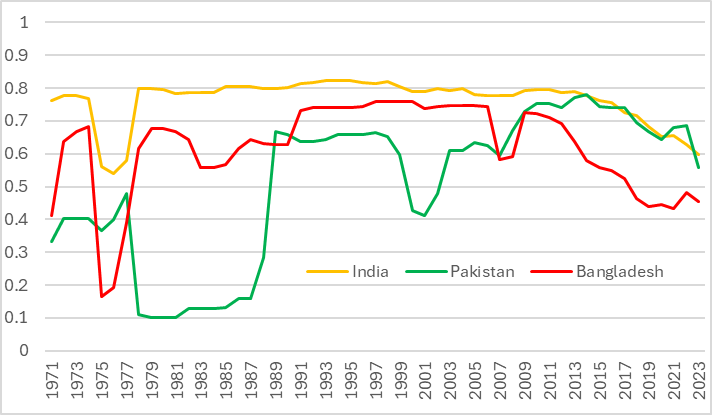

Competitive elections also require robust political parties and organizations, which is measured by the ‘Freedom of Association Index.’ Chart 3 indicates that freedom of association in Bangladesh has been declining since 2007.

Another crucial element for free and fair elections is a dynamic media landscape.

The Freedom of Association Index also evaluates the extent to which the government respects press freedom, the ability of citizens to discuss political issues publicly and privately, and the freedom of academic and cultural expression.

Unsurprisingly, freedom of speech in Bangladesh has sharply decreased since 2007. Notably, freedom of expression has also been waning in India and Pakistan, with Indian media freedom nearing the dismal state seen in Bangladesh prior to the Monsoon Revolution.

In other words, the decline of electoral democracy in Bangladesh is closely tied to the erosion of freedom of expression and association. It's important to note that democracy encompasses more than just elections.

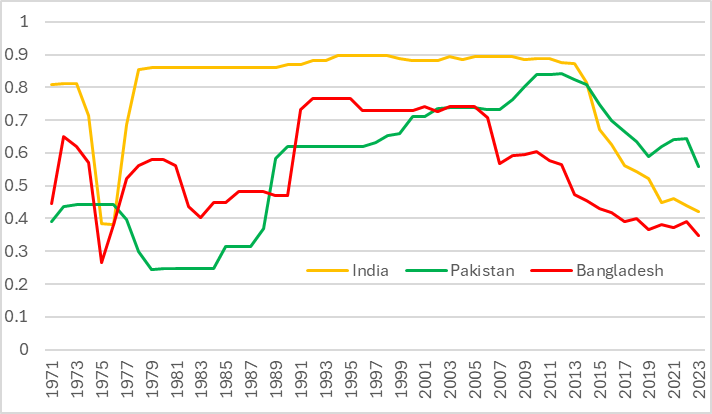

For instance, the ‘Judicial Constraint on the Executive Index’ assesses the transparency and enforcement of laws, the impartiality of public administration, and citizens' access to justice.

Chart 5 presents a troubling picture for Bangladesh until recently, showing a judiciary that has been more undermined than any in the region over the past fifty years.

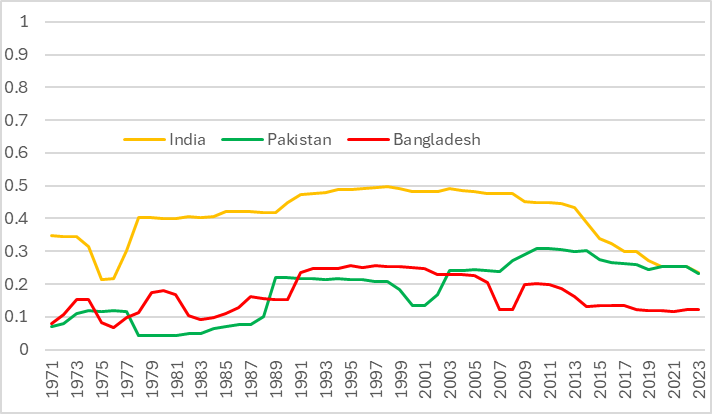

Taking a broader view beyond elections, the V-Dem Institute also publishes indices that examine other facets of democracy.

The ‘Liberal Democracy Index’ gauges the extent to which individual rights are upheld, while the ‘Participatory Democracy Index’ measures citizen involvement in governance through civil society organizations or local governments.

Charts 6 and 7 illustrate these two indices, revealing similar trends as those seen in electoral democracy: Bangladeshi democracy was strongest between 1991 and 2006; Pakistani democracy has been at its peak since 2008; and Indian democracy has been in decline since 2014.

Considering the evolution of democracy over the past six decades, what might the 2024 elections indicate about the future?

While events in Pakistan unfolded largely as anticipated, it may be too early to draw conclusions about India. One interpretation of the Indian election results suggests that voters rejected Prime Minister Modi's attempt to secure a decisive majority due to concerns about its implications for democracy. If this interpretation holds true, there may be a glimmer of hope for democracy in the region.

Bangladesh has, of course, distanced itself from its undemocratic past following the Monsoon Revolution.

The interim administration has proposed a roadmap for restoring democracy through free and fair elections, along with efforts to strengthen the Republic to prevent any future derailment of democratic processes.

Let’s hope that in a few years, these charts will be updated to reflect a strong upward trend, marked by red lines indicating progress.

—

J Rahman is an economist and a writer