No more drip diplomacy: Bangladesh must choose side in fighting against India’s silent water colonialism

While global attention remains riveted on battlefields and ballot boxes, South Asia is witnessing a quieter– but no less dangerous–war over a most fundamental resource: water. And no actor plays this game more ruthlessly than India.

When New Delhi openly threatens to exit the Indus Waters Treaty– a rare diplomatic success story in a volatile region– it doesn’t just rattle Pakistan. It signals a breakdown of the international norms that have, until now, governed transboundary rivers.

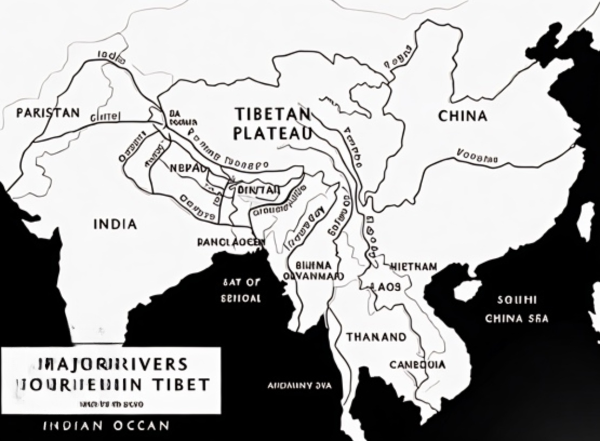

But Pakistan is only the tip of the iceberg. From Nepal to Bangladesh and even parts of China, nations across the region are grappling with what can only be described as Indian hydro-hegemony.

India's dam-building frenzy is essentially about control. From the Farakka Barrage that starves Bangladesh of dry-season flows, to the Tipaimukh and Teesta projects that remain mired in controversy, the pattern is clear: New Delhi treats every river that touches its territory– upstream or down– as its sovereign asset.

Agreements are signed under duress, cooperation is conditional, and transparency is absent.

Take Nepal, the source of vital rivers like the Koshi, Gandak, and Mahakali.

Decades-old treaties– the Koshi (1954), Gandak (1959), and Mahakali (1996)-- handed India overwhelming control. When disasters strike, like the catastrophic 2008 Koshi embankment breach that ravaged five Nepali districts, it's Nepal that pays the price.

Despite being upstream, Nepal has been politically and hydrologically subordinated– an inversion of geography by the sheer weight of Indian dominance.

In Bangladesh, the numbers speak volumes: out of 54 transboundary rivers, there is just one formal treaty– the 1996 Ganges Water Treaty– and India routinely violates even that.

Upstream diversions have reduced dry-season flows by up to 60 percent, crippling agriculture. Sudden floodwater releases have caused over $750 million in crop damage annually. Dhaka’s repeated pleas for equitable sharing fall on deaf ears.

In Pakistan, India’s dam construction on the western rivers– Kishanganga, Ratle, Baglihar– defies the spirit and letter of the Indus Waters Treaty, one of the world’s most robust water-sharing frameworks.

Now, with Delhi toying with the idea of withdrawal, it is venturing into dangerous legal territory, violating Article 60 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

Even China, often portrayed by India as the regional water villain, has never violated a formal water agreement. Yet India continues building controversial dams in Arunachal Pradesh, while opposing China's hydropower projects in Tibet.

This hypocrisy– combined with Delhi’s refusal to share crucial hydrological data with Bangladesh– underscores a larger strategy: assert control upstream, deny accountability downstream, and blame everyone else.

Legal frameworks India

ignores

New Delhi still refuses to ratify the 1997 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses– a treaty that enshrines three basic principles of cross-border water justice: equitable use, no significant harm, and prior consultation.

In its absence, India has given itself a free pass to engineer ecological collapse beyond its borders, with no legal accountability and no regard for the fallout.

The consequences are nowhere more visible than in Bangladesh. Under a succession of India-aligned governments– most notably the Awami League– Dhaka has been reduced to a client state in water negotiations.

The so-called “model friendship” has delivered anything but: the north suffers creeping desertification in Rajshahi and Naogaon, salinity encroaches deep into the Sundarbans, irrigation canals run dry across Rangpur, and the traditional fishing economy is collapsing.

The UNESCO-listed Sundarbans– the world’s largest mangrove forest– is now at risk of delisting due to upstream manipulation. Nearly 30 million Bangladeshis are now living with water insecurity engineered upstream in Delhi.

And yet, instead of demanding justice, Bangladesh’s leadership echoed Indian talking points. When questioned about India-triggered flooding, ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina went so far as to call the deluge “a blessing” for delivering fertile soil– a comment as revealing as it is absurd, and one that perfectly encapsulates the submissiveness of a government dependent on Indian patronage.

But the tide may be turning.

China, often demonized by Indian media as the great upstream threat, is now moving decisively to alter the balance. Under its 14th Five-Year Plan, Beijing is building the world’s largest dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo– the Brahmaputra in India and Bangladesh.

Once completed, it will give China unprecedented control over more than 60% of the river’s upper stream– directly shaping flows into Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, and the downstream plains of Bangladesh.

Pakistan, long caught in the crosshairs of India’s dam projects in Kashmir, is now working closely with Beijing on real-time hydrological surveillance and satellite monitoring.

This partnership strengthens Islamabad’s ability to track, document, and legally challenge Indian violations of the Indus Waters Treaty.

And then there is Nepal– historically treated by India not as a sovereign partner but as a geographic extension of its own water infrastructure. Yet Nepal sits atop the headwaters of the Koshi, Gandak, and Mahakali rivers, giving it latent leverage it has never been allowed to exercise.

Now, with anti-India sentiment on the rise and a staggering 83,000 MW of untapped hydropower potential, Kathmandu is beginning to reimagine its role–as a sovereign actor in a new, trans-Himalayan water coalition.

The working principle of an alliance

Bangladesh must stop playing junior partner and start acting like a sovereign nation as well.

That means aligning with others who share its struggle– China, Pakistan, and Nepal– to build a South Asian Water Alliance capable of confronting Delhi’s dominance with unity, technology, and strategy.

Such a coalition could transform the regional water landscape. Through joint satellite surveillance, these countries could track India’s upstream activities in real time–exposing unauthorized diversions, dam releases, and treaty breaches.

Together, they could pursue legal recourse at the International Court of Justice, UNEP, and UNFCCC, where ecological sabotage and unilateralism can no longer hide behind bilateral silence.

With China's financing power, the alliance could launch shared infrastructure and energy projects that bypass Indian influence entirely.

But beyond deterrence, this alliance would bring something Bangladesh has never truly had: independence in managing floods, droughts, and data.

Coordinated early warning systems, real-time hydrological sharing, and region-wide oversight under a potential UN-backed River Basin Authority could end the country’s reliance on Delhi’s selective, politicized water drip.

The first step is clear: Bangladesh must immediately approve China’s long-standing proposal to rehabilitate the Teesta River system. The plan includes reservoir construction, irrigation expansion, and restoring ecological flow– exactly what the Indian state of West Bengal has blocked for over a decade with bureaucratic deflection and political theater.

India has predictably objected, hiding behind the euphemism of waiting for a “fully elected government” in Dhaka. But this is not about elections– it’s about ensuring another pliant regime that bows to Delhi’s hydraulic whims.

Bangladesh must stop mistaking water strangulation for regional harmony. The Teesta debacle has lasted 13 years. In that time, India has diverted the river’s flow, paralyzed negotiation under the pretense of “state-level issues,” and left northern Bangladesh to wither.

The result? Dying cattle, failed crops, shrinking rivers– and a stream of condolences from the very hand that cut the flow.

Successive governments in Dhaka have clung to the hope that loyalty to Delhi would earn reciprocity. What did they get in return? A ballooning trade deficit. Transit routes for India, but no access in return.

Cultural dominance through media exports. And now, the final blow– a tightening noose on the country’s water lifelines.

It’s time to say enough. Water is not a gift to be granted– it is a right to be defended. And defending that right means making a choice: sovereignty or servitude.

—

Arif Hafiz is a political analyst, cultural critic, and independent columnist.