Mujib’s legacy has lost its social capital for now…but many like Mahfuz Anam has failed to grasp it

In the 90s, during the BTV era, a show called Dark Justice gained immense popularity in Bangladesh. It aired during prime time on Sundays, and I still remember its opening credits, featuring Judge Nicholas Marshal (played by Rami Zada) reflecting on his experiences:

"As a cop, I lost my cases to legal loopholes, but I believed in the system. As a district attorney, I lost to corrupt lawyers, but I believed in the system. As a judge, I was constrained by the law, but I believed in the system. Until they took my wife and kids away. Then I stopped believing in the system."

Like Judge Marshal, we all have our limits of tolerance—whether it's dealing with nonsense from superiors or government officials.

The past decade has seen a wave of unrestrained praise for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman during Sheikh Hasina’s 15-year tenure, which has likely tested the patience of many citizens, except for those who are ardent Awami League supporters or beneficiaries of that fascist regime.

As a reporter, I couldn't escape the constant stream of praise that often felt like worship, especially since I had to cover events like press briefings and seminars attended by Awami League ministers.

Then came the Mujib Barsha initiative, and the frenzy we witnessed was overwhelming. Mujib corners appeared in every corner of even private offices.

The historic 7th March speech—acknowledged by many, even staunch opponents of Awami League, for its power and impact—was played so frequently and for so long that it became a source of mockery, a nuisance, and an annoyance.

I endured all of this until I reached my breaking point. It happened during a Biman Bangladesh flight from Bangkok to Dhaka.

About half an hour from Dhaka, the entertainment system was abruptly taken over (as it usually is for pilot announcements) to play the 7th March speech for what felt like five long minutes.

I could see the deep irritation on the faces of fellow passengers—both locals and foreigners. One passenger even exclaimed loudly, “Even North Korea probably doesn’t do this.”

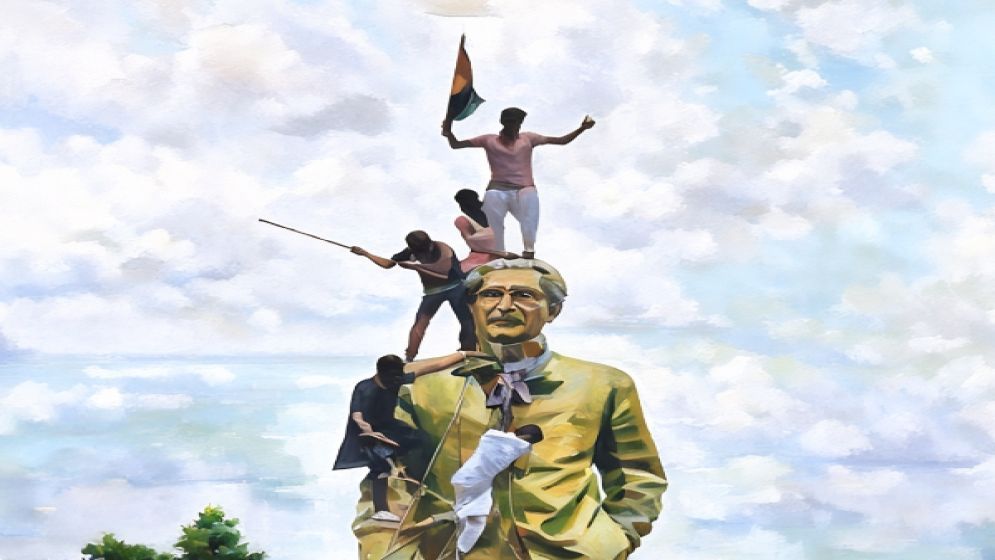

Attacks on

symbolism

Within hours of Sheikh Hasina’s disgraceful fleeing from Bangladesh in face of a massive student-led uprising, almost all symbols of Sheikh Mujib were brutally destroyed.

The large bronze statue at Bijoy Sarani, the mural works in front of Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport, even the statue and mural works inside the cantonment areas were destroyed.

The House no-32 in Dhanmondi which was turned into a museum and was visited by almost every major state guest and dignitaries in the past one decade was burnt down and destroyed.

When a regime collapses, the first casualties are often the statues of figures who represented it.

After the Soviet Union fell in 1991, many statues of Soviet icons like Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin were toppled. Similarly, on April 9, 2003, Iraqi civilians destroyed a large statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad's Firdos Square, marking the end of his oppressive rule in Iraq.

So, those attacks on Mujib's statues, murals, and even his house obviously reflected a deep-seated public frustration with the Hasina regime.

This frustration stems not only from a perceived oppressive atmosphere but also from the regime's persistent attempts to rewrite history and establish a dynasty centered around Mujib and his descendants.

Moreover, the anger directed at certain structures is understandable given the events of the long July revolution.

Hasina’s choice to prioritize visits to the "damaged metro rail stations and BTV buildings" instead of first reaching out to the families of those who lost their lives in the July protests has understandably sparked significant public resentment and outrage.

The destruction

of a convoluted legacy

Mujib’s legacy—or at least the “distasteful and falsified” version that the Hasina regime has imposed on us over the past decade and a half through a vulgar display of partisanship—has been completely eradicated in the new post-revolutionary Bangladesh.

This shift didn’t occur because the massive revolution toppled Hasina’s regime; it began long ago when she started force-feeding us a distorted narrative of history regarding her father’s legacy.

Hasina's regime initiated a form of cultural fascism, capturing the public imagination by initially promoting the narrative of the liberation war's glory.

However, this narrative was cleverly packaged to present her party, the Awami League, as the sole bearers of its legacy.

This effectively erased the contributions of other parties, groups, and even ordinary individuals who played a crucial role in Bangladesh's independence struggle.

People didn’t openly express their anger towards the blatant and distorted narrative surrounding Mujib and the worship of him, as Hasina was very sensitive to any criticism of her family.

Laws like the Digital Security Act were enacted to target those who dared to voice such criticism online.

However, the reality is that Hasina’s version of Mujib's legacy lost its social capital long before her disgraceful ousting. It was her government’s unlawful and undemocratic use of power that silenced dissent.

The situation has now changed, which explains the backlash against the recent column by The Daily Star editor Mahfuz Anam.

Titled “Hasina’s Misrule Should Not Affect Our Judgment of Bangabandhu,” this column by the veteran editor is, in truth, quite balanced and nuanced—contrary to what the headline might suggest, which could lead some to think Anam was overtly supporting Mujib.

In this column, editor Anam wrote that Bangabandhu (the honorific title given to Mujib throughout the article) must be judged in two distinct phases: his leadership leading up to independence, and his actions after returning to Bangladesh on January 10, 1972.

Anam argues that we must not judge Mujib in light of the authoritarian and corrupt rule of his daughter and we cannot allow Sheikh Hasina's actions during her 15-plus years in power to overshadow Mujib’s historic and indisputable role in achieving Bangladesh's independence.

For a neutral reader, these lines might have made sense before the long July revolution, as they contain elements of truth. However, the scars of that revolution remain fresh in our minds and hearts.

Most of the general populace now find it hard to tolerate a troubled legacy—one that a fascist ruler has exploited to maintain power while seeking to extend her rule over the deaths of more than 1,500 people in just three weeks.

Like Judge Marshal, they have collectively reached their limit of tolerance regarding Mujib, Hasina, and the complicated legacy of a prominent political family in Bangladesh.

The lemon has been squeezed so thoroughly that it has turned bitter, and editor Anam has failed to grasp the sentiment of the people.

—-