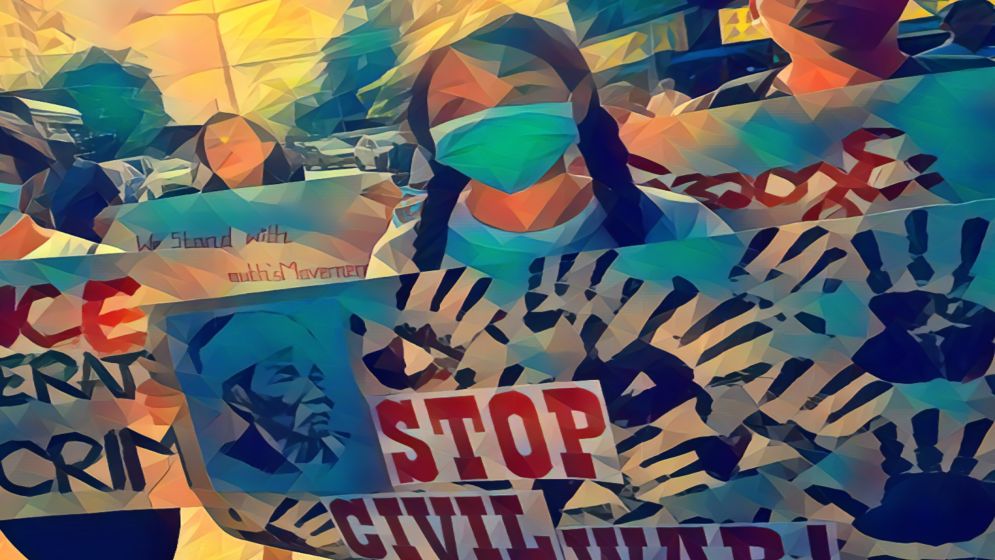

Myanmar’s unresolved crisis: Civil war, political dynamics, and the Rohingya repatriation dilemma

In October 2023, the coordinated offensive operations by the "Three Brotherhood Alliance" (3BA)—comprising the Arakan Army (AA), the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA)—appeared to proceed with tacit approval from China.

This escalation galvanized various Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs), including the People's Defense Force (PDF), the armed wing of the National Unity Government (NUG) led by Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy.

The simultaneous nationwide attacks stretched the Myanmar military, or Tatmadaw, beyond its capacity, particularly in ground engagements.

The Tatmadaw faced a sharp decline in morale, with numerous defections and surrenders to EAOs. Its ability to reinforce critical areas was significantly hampered, while recruitment efforts yielded limited success.

As a result, the military increasingly relied on airstrikes and intermittent artillery bombardments to counter EAOs and their supporters.

Currently, approximately 60% of Myanmar's territory is under EAO control. On October 9, the Kachin Independence Army captured Pinlebu, a major city in the Sagaing Region.

Earlier, in August, Lashio, the capital of Shan State and the seat of the Northeast Command, fell to the MNDAA. The TNLA continues its northern Shan State offensive, recently seizing the strategic township of Hsipaw.

These advances suggest that EAOs are gradually converging on the Central Command in Mandalay, posing a direct threat to the Tatmadaw's authority and legitimacy.

In Rakhine State, the Arakan Army has made significant progress against the junta's forces to capture the Western Command.

However, the Tatmadaw, reportedly aided by a newly formed Rohingya militia, has managed to halt AA advances around Maungdaw, a key Rohingya stronghold and strategic township.

This collaboration has exacerbated tensions between the AA and the Rohingyas in the region.

Despite challenges to its morale, the Tatmadaw retains control over key strategic and economic centers, including administrative hubs, the military-industrial complex, seaports, and airports.

Its physical and organizational capacity remains intact, preventing a complete collapse for the time being.

The economic dynamics

In the three years since Myanmar's 2021 coup, the country's foreign trade, though reduced, has remained significant, amounting to approximately $105 billion, with $27 billion generated from border trade.

Myanmar operates 17 border trade stations across five neighboring countries: China (5 stations), Thailand (7), India (2), Bangladesh (2), and Laos (1).

Daily trade volumes are substantial with China ($10 million) and Thailand ($14 million), but minimal with Bangladesh, at just $35,000.

Of these border trade stations, six are controlled by Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs), which have collectively earned $10 billion from trade over the last three years.

This reflects the emergence of a "war economy," where all parties—EAOs, the junta, and other stakeholders—derive political and economic benefits from sustained conflict rather than seeking decisive victories.

Revenue streams include external financial support, looting, drug trafficking, arms smuggling, and human trafficking, all of which thrive on ongoing violence.

These illicit activities have significantly impacted China's Yunnan Province, prompting China to advocate for regulated trade in the border regions.

As a result, the junta and EAOs have established profit-sharing arrangements in border trade to maintain a fragile status quo.

However, this arrangement is precarious and could collapse, potentially fueling a resurgence of the illicit economy.

Among the EAOs, the MNDAA, TNLA, and KIA collectively earn $10 million daily from border trade, while the Karen National Army benefits from $14 million.

In contrast, the Arakan Army (AA), operating along the Bangladesh border, earns only $35,000 per day.

This limited financial incentive from border trade discourages stronger ties with Bangladesh, pushing the AA toward more profitable illicit activities such as human trafficking and arms smuggling.

The China factor

China seeks stability in Myanmar or a balanced power dynamic between the junta and Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) to ensure the progress of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects and the protection of its strategic interests.

Another priority for Beijing is increasing regulated border trade through a profit-sharing mechanism between the junta and resistance forces, which could help curb illicit activities along the China-Myanmar border.

Such activities have negatively impacted Yunnan Province and its residents, a concern that had previously gone unaddressed by the junta in Myanmar’s China-bordering regions.

In response, the "Three Brotherhood Alliance" (3BA) was reportedly encouraged to launch Operation 1027.

Following the operation, China brokered a peace initiative between the junta and 3BA, resulting in a ceasefire at the start of 2024.

Although there were subsequent discussions, no concrete agreement on border trade was reached, and the region remains unstable.

Since the 2021 coup, China had maintained a certain distance from the junta, as evidenced by its tacit approval of 3BA operations in Northern Shan and Kachin States, bordering China.

However, a recent shift in Beijing’s approach is apparent. During Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi's visit to Naypyidaw on August 11, 2024, China extended a gesture of legitimacy to the junta by inviting its leader, Min Aung Hlaing, to Beijing.

Reports suggest that Chinese Premier Li Qiang may meet Min Aung Hlaing to discuss Myanmar’s upcoming 2025 elections, signaling a recalibration of China’s policy toward Myanmar.

During Wang Yi’s visit, the junta requested that China withdraw its support for EAOs, pledging in return to safeguard China’s interests in Myanmar.

Meanwhile, Deng Xijun, China’s special envoy for Myanmar, expressed concerns about the EAOs’ growing ties with the West, particularly with the National Unity Government (NUG) and its armed wing.

In discussions with leaders of the powerful Wa State Army, Deng emphasized that the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) remains the foundational and most critical political force in the country, stating that neither the NUG nor the National League for Democracy (NLD) could replace it.

He further noted that the MNDAA’s capture of Lashio had destabilized northern Myanmar, potentially creating an opening for the U.S.-led Western interference.

In response, China has imposed punitive measures on the MNDAA and TNLA, cutting off supplies and essential logistics.

Additionally, Beijing has warned the Wa State against supporting these EAOs. This shift in stance has emboldened the junta, which has intensified bombing operations in Lashio to reassert control over the area.

The West, India and ASEAN factors

The Indo-Pacific strategy, along with initiatives like the Quad and AUKUS, reflects the West’s broader approach to containing China’s influence.

However, these efforts have been significantly counterbalanced by China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Pakistan-China Economic Corridor (CPEC), and the Myanmar-China Economic Corridor (MCEC).

The Rohingya crisis and Myanmar’s 2021 coup have provided the U.S. with an opportunity to deepen its involvement in the region through measures like the Burma Act.

This legislation aims to isolate the junta, impose sanctions, support pro-democracy forces, and offer technical and non-lethal assistance to Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs), thereby undermining the junta and curbing China’s sway in Myanmar.

Additionally, a forthcoming Rohingya Act from the U.S. could further challenge China's influence in addressing the Rohingya issue, particularly in the strategic Bay of Bengal region.

Recently, remarks by Mizoram’s Chief Minister about the potential for a Christian country in the tri-border region of India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar suggest a broader, West-backed missionary initiative.

This vision hints at a long-term plan to establish a buffer state, potentially disrupting China-Myanmar connectivity and influence in the region.

Meanwhile, India, despite being a democracy, has historically supported Myanmar’s junta for three key reasons:

Strategic Connectivity: Myanmar plays a crucial role in India’s "Look East" and "Act East" policies, with projects like the Kaladan Multimodal Project and the India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway being vital for regional connectivity.

Counter-Insurgency Efforts: India relied on the junta’s cooperation to combat insurgency by targeting militant sanctuaries within Myanmar.

Regional Power Dynamics: From a strategic perspective, India sought to prevent Myanmar from falling entirely under China’s influence.

These considerations led India to back Myanmar’s junta, even amidst the Rohingya genocide and humanitarian crisis.

However, with the junta now facing mounting challenges and the prospect of a military defeat becoming more plausible, India appears to be adjusting its stance.

Recognizing the growing influence of resistance groups, India, for the first time, invited representatives from the National Unity Government (NUG), the Arakan Army (AA), the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), and the Chin National Front to a seminar titled “Constitutionalism and Federation” in New Delhi on September 24, 2024.

This marks a significant shift in India’s approach to the evolving situation in Myanmar.

Now, ASEAN’s efforts to address the Rohingya crisis have been relatively modest. While individual member states, such as Malaysia, demonstrated proactiveness, significant progress was hindered, largely due to ASEAN’s principle of non-interference in member states' internal affairs.

Following Myanmar's 2021 coup, however, ASEAN took a more vocal stance, aiming to address the broader humanitarian crisis in Myanmar, including the Rohingya issue.

Two years ago, ASEAN proposed a Five-Point Consensus for Peace, but its implementation has stalled due to the junta’s lack of cooperation.

At the ASEAN Summit in Laos on October 9, 2024, Thai Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra suggested holding an informal consultation in December to explore potential solutions for Myanmar.

For the first time in three years, Myanmar participated by sending a senior foreign ministry official to the discussions. ASEAN views this as a positive development and a potential step toward resolving the crisis.

Bangladesh factor and my take

Bangladesh’s foreign policy has often been cautious and restrained, avoiding confrontation even in cases where its interests have been undermined.

For instance, it was Gambia—not Bangladesh—that filed the case against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) regarding the Rohingya genocide.

The ICJ hearings took place from December 10–12, 2019, in The Hague, while, during nearly the same period (December 11–14, 2019), Bangladesh’s Army Chief was on a visit to Myanmar.

This visit seemingly signaled that Bangladesh viewed the Rohingya issue as Myanmar’s internal affair. Furthermore, Bangladesh refrains from officially recognizing the displaced population as "Rohingya," instead labeling them as Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMN), aligning with Myanmar's objection to the term "Rohingya."

It remains unclear whether Bangladesh has an independent and coherent policy or strategy for Rohingya repatriation, as no such framework has been made public.

Dhaka has historically relied on the goodwill of regional powers like India and China and the broader international community, both of which prioritize their own strategic interests.

While these actors may provide humanitarian assistance, they are unlikely to risk their geopolitical agendas for Rohingya repatriation. If Bangladesh itself lacks a clear strategy, it cannot reasonably expect others to champion the cause.

Rohingya repatriation has not been a central priority for Bangladesh. For the ruling Hasina government, especially post-2014, the focus has largely been on securing its political legitimacy through the diplomatic efforts of its missions abroad and domestic institutions.

In this context, the regime's interests have often overshadowed national interests. The Rohingya crisis, while significant, has not posed an existential threat to the government’s stability.

Notably, after Myanmar’s 2021 coup, Bangladesh did not engage with the Arakan Army (AA), despite its rising influence in Rakhine State.

In 2022, AA Chief Major General Twan Mrat Naing expressed sympathy for the Rohingya and voiced a willingness to reintegrate them into Rakhine as part of Myanmar. In return, he sought Bangladesh's humanitarian support and solidarity with the Rakhine people.

However, Dhaka did not respond to these overtures. Over time, the AA’s stance shifted, and the group began referring to Rohingyas as "Bengali Muslims," with repatriation no longer on their agenda. Some Rakhine journalists now even call Rohingyas "Chittagonians," further complicating their identity and prospects for repatriation.

A significant faction within Rakhine's political landscape is open to discussing various development initiatives with Bangladesh, but they remain unwilling to address the Rohingya repatriation issue.

It appears that key opportunities to engage on this matter have slipped away. The junta no longer holds legitimate authority over Myanmar and has lost control of much of its administration.

If repatriation occurs, the Rohingyas would return to Rakhine, which is now largely under the control of the Arakan Army (AA). The AA has established its own judiciary, police, and civil administration across most of Rakhine, except for the military-occupied state capital and a few towns.

However, Dhaka continues to engage exclusively with the junta, while neighboring countries pragmatically interact with both the junta and Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) along with their political entities.

Recently, the UN warned of an impending famine in Rakhine. Agricultural production has plummeted, and trade has nearly ceased, leaving two million out of Rakhine's three million people at risk of starvation.

Sixty percent of the population has been displaced, and over half a million are now entirely dependent on aid. The junta's "Four Cuts Strategy," which restricts access to food, medicine, and intra- and inter-state movement, has exacerbated the humanitarian crisis.

The situation in Rakhine has taken a new and troubling turn. While the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military) has long been accused of persecuting the Rohingyas, recent reports suggest that the AA is now targeting them as well.

This has triggered a fresh wave of refugees fleeing into Bangladesh. Unlike the Tatmadaw, whose persecution led to large-scale Rohingya exodus and who did not deny allegations of expulsion, the AA's actions have caused smaller, ongoing displacements.

However, the AA denies involvement in these incidents, further complicating the crisis.

The National Unity Government (NUG) has stated its commitment to repatriating Rohingyas with equality and dignity once stability is restored and democratic forces return to power in Myanmar.

The NUG has also pledged to hold accountable those responsible for human rights violations and genocide against the Rohingya. Despite this, Dhaka has not meaningfully engaged with the NUG.

At a seminar in Dhaka last year, the NUG's Foreign Minister, speaking online, expressed frustration over the lack of engagement from Bangladesh.

It appears that the interim government, preoccupied with other pressing issues, is likely to overlook engagement with the NUG, missing yet another opportunity.

At present, Rohingya repatriation does not seem to be a priority for either Dhaka or the NUG, nor is it in the interest of Rakhine or the Arakan Army (AA). This underscores the grim reality of the repatriation process.

It is vital to remember that if we remain indifferent to the pain and suffering of our neighbors, they are unlikely to consider our concerns during their moments of prosperity and success.

—--

Lieutenant General (Retd.) Muhammad Mahfuzur Rahman is the Former Principal Staff Officer, Armed Forces Division, Bangladesh.