Bangladesh's dark chapter: Enforced disappearances and a cry for justice

Tanjimul Haque and Nusrat Jahan

Publish: 09 Dec 2024, 11:46 AM

Imagine being swallowed by the earth, your existence erased, leaving your loved ones to mourn a loss they cannot even confirm.

This was the chilling reality of enforced disappearances, a dark stain on Bangladesh's human rights record during the deposed Sheikh Hasina regime.

Take, for example, Michael Chakma, a leader of the United People's Democratic Front. After five years in a secret detention center, he reemerged—like a ghost returning to a world that had moved on. His case, though harrowing, is not an isolated one.

Others, like former Brigadier General Abdullahil Aman Azmi, Mir Ahmad Bin Quasem, and M Maroof Zaman, have similarly disappeared into the shadows, only to return bearing the haunting marks of isolation and trauma.

These stories point to a grim pattern: the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), an agency enshrouded in secrecy, was widely believed to be behind many of these disappearances in the last one decade or so.

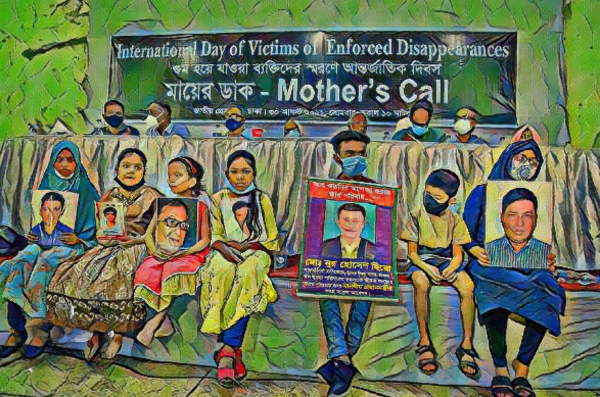

The families left behind are still left to endure the painful uncertainty, while society as a whole is gripped by fear. But accountabilities of the perpetrators still remain elusive.

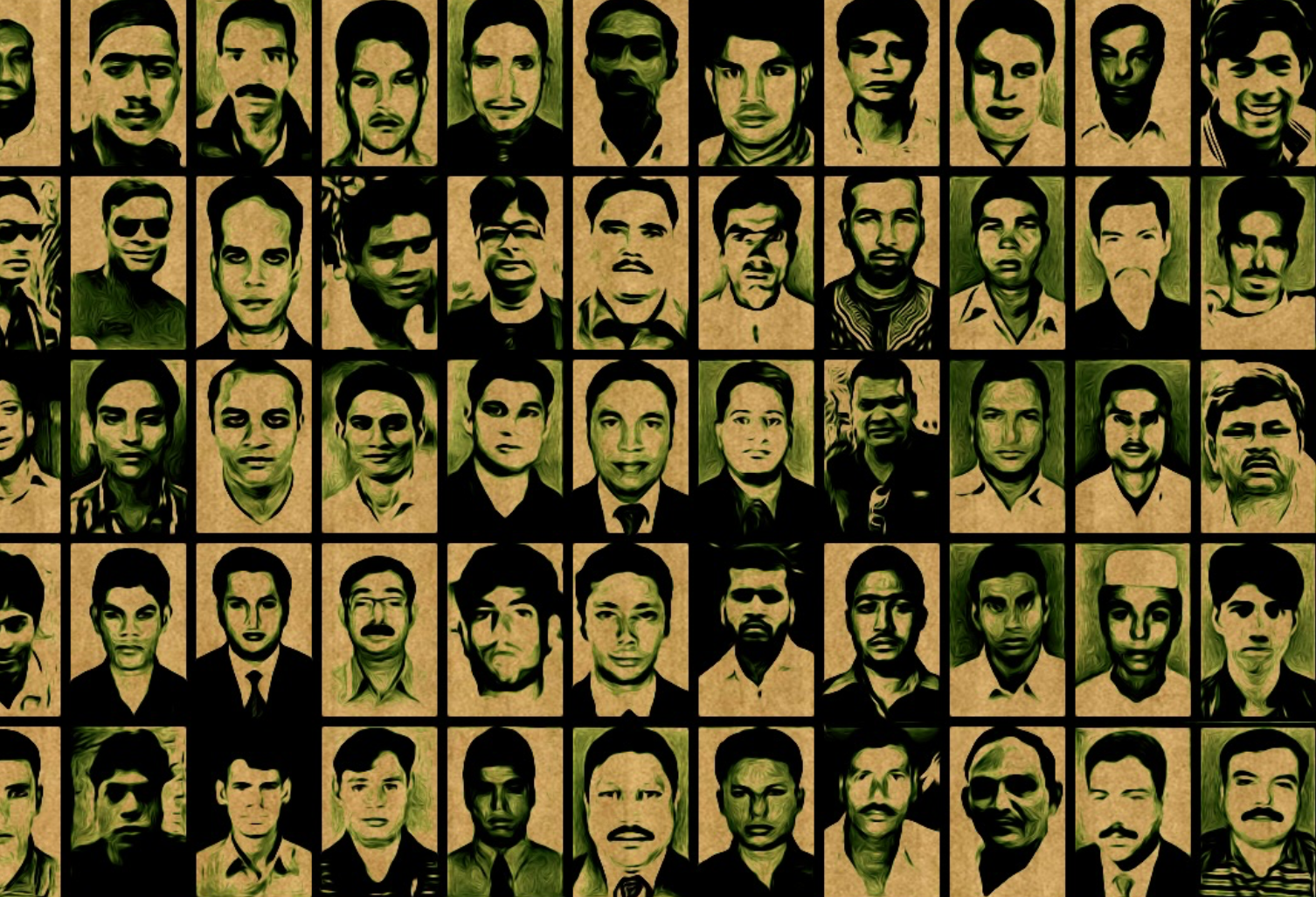

Since 2009, Odhikar, a Bangladeshi human rights organization, has documented a staggering 708 cases, revealing the deep-rooted impunity that perpetuates this crime.

While Bangladesh's recent ratification of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances represents a positive shift, it is just the first step in a long, difficult process.

Amnesty International's Smriti Singh rightly calls it "a crucial first step" toward achieving truth, justice, and reparations.

The Convention clearly defines enforced disappearance as a crime against humanity, affirming the right to be free from such acts under all circumstances.

It obligates states to criminalize and punish these violations. However, Bangladesh has yet to pass specific legislation to fully address this grave issue.

The chain of command leads to

the top

The disappearances that have plagued Bangladesh for years are not simply the acts of rogue agents. They are systemic, pointing to a chain of command that reaches the highest levels of power.

The doctrine of superior responsibility, a cornerstone of international criminal law, makes this abundantly clear. Those in positions of authority cannot shield themselves from culpability when their subordinates commit heinous crimes.

From 2009 to 2024, during the Awami League's rule, enforced disappearances became a chillingly familiar occurrence.

The evidence suggests a pattern of state-sanctioned abductions and secret detentions. This raises serious questions about why Bangladesh delayed for so long in acceding to the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances.

Could it be that the very institutions implicated in these crimes sought to avoid scrutiny?

The principle of command responsibility leaves no room for doubt: superiors, including those at the apex of power, bear responsibility for the actions of their subordinates.

This implicates then-Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and other ministers who exerted control over law enforcement agencies.

Even without direct evidence linking them to specific cases, their failure to prevent, investigate, or punish these crimes renders them accountable. Their inaction, their silence, speaks volumes.

The convention against

enforced disappearance

On September 28, 2024, Bangladesh took a crucial step forward in its human rights journey with the ratification of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances.

This marks a pivotal moment in the nation’s effort to address the pervasive issue of enforced disappearances, signaling a renewed commitment to accountability and justice.

The Convention categorizes enforced disappearance as a crime against humanity, placing it on the same level as the atrocities committed during World War II.

The Nuremberg and Tokyo trials, which held Nazi and Japanese war criminals accountable, set a global precedent for prosecuting those responsible for such heinous acts—regardless of their position or status.

The case of Chile’s Augusto Pinochet further reinforced this principle, proving that even the most powerful figures are not immune to prosecution.

Pinochet, who was responsible for widespread killings, torture, and enforced disappearances, was arrested in London and faced extradition on charges of crimes against humanity.

His arrest shattered the myth of impunity for dictators and provided hope for victims seeking justice.

In recent years, the prosecution of former heads of state for war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity has become a cornerstone of international justice.

Leaders such as Jean Kambanda of Rwanda, Slobodan Milošević of Serbia, and Charles Taylor of Liberia have been convicted in international courts, highlighting the growing global consensus on individual accountability for heinous acts.

Now, Bangladesh has the opportunity to demonstrate its dedication to upholding human rights and ending the devastating practice of enforced disappearances.

The Convention offers a solid framework for investigating these crimes, prosecuting the perpetrators, and providing justice to victims and their families.

The interim government must act decisively. It must establish an independent and specialized authority tasked with investigating past disappearances, ensuring that no case goes unexamined.

Those responsible for these crimes—no matter their rank or political affiliation—must be pursued and held accountable under the full force of the law.

By fully embracing the Convention, Bangladesh has the chance to send a powerful message to the international community: enforced disappearances will no longer be tolerated, and justice will prevail.

Holding perpetrators of

enforced disappearance accountable

However, Bangladesh's commitment to ending enforced disappearances will be judged not by words, but by deeds. The International Convention demands action, and that action must include pursuing perpetrators wherever they may flee.

The Convention mandates that states investigate cases of enforced disappearance, detain suspects, and initiate prosecutions. Crucially, it also establishes enforced disappearance as an extraditable offense, closing off avenues of escape for those who seek to evade justice.

Bangladesh must now establish a dedicated authority empowered to investigate these crimes, protect victims and witnesses, and pursue legal action. This authority must have the teeth to access all detention facilities, ensuring that no potential victim remains hidden in the shadows.

The case of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who reportedly fled to India following a change in government, highlights the importance of extradition.

Bangladesh has an extradition treaty with India, and the interim government must utilize this legal framework to seek her return if credible evidence links her to enforced disappearances.

The Convention makes it clear that enforced disappearance is not a political offense. This prevents states from denying extradition requests on political grounds, a crucial provision in ensuring accountability.

Even in cases where no extradition treaty exists, Bangladesh can leverage international conventions to pursue justice.

Bangladesh must also embrace the oversight mechanism of the Committee on Enforced Disappearances. Accepting the Committee's authority will allow victims to file complaints and seek redress, further strengthening the framework for accountability.

The message is clear: there can be no safe haven for those who orchestrate or condone enforced disappearances.

Confronting the scourge of

enforced disappearances

Allegations against former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and her administration have sparked renewed concerns about accountability under international law, particularly regarding the state’s failure to accede to the Convention on Enforced Disappearances until recently.

This hesitation raises broader questions about the Bangladeshi authorities' commitment to justice and human rights.

Under the Convention, enforced disappearance is defined as a crime against humanity, which is uniquely focused on individual criminal responsibility, not state responsibility. As such, it is individuals—rather than the state itself—who are held accountable for these violations.

From 2009 to 2024, the period under Sheikh Hasina’s rule, reports of enforced disappearances have been widespread, with law enforcement agencies implicated in these crimes.

This raises the question of individual criminal responsibility for those in power during this time, including Hasina herself.

The principle that heads of state are not above the law was firmly established by the Pinochet case, which showed that a leader’s official position does not grant immunity from prosecution for crimes such as torture or crimes against humanity.

As the enforced disappearances in Bangladesh are not part of the legitimate duties of a head of state, it is clear that those responsible, including Hasina, must face accountability for their actions.

The challenge of accountability is further complicated by the passage of the Father of the Nation Family Members' Security Act in 2009, a law introduced by the Awami League government that granted special protection and immunity to the family members of Bangladesh's founding leader.

However, this law was repealed in September 2024 through an ordinance, rendering the immunity it conferred null and void.

In the absence of legal protection, it is clear that neither the former Prime Minister nor any law enforcement official involved in enforced disappearances can be shielded from prosecution.

The issue also extends beyond Bangladesh’s borders. Many individuals implicated in these crimes have reportedly sought asylum in other countries, with India allegedly offering refuge to Sheikh Hasina and other political figures accused of involvement in enforced disappearances.

By granting asylum to individuals implicated in serious human rights violations, India and other nations may be violating their international obligations to ensure that perpetrators of such crimes are brought to justice.

International law obligates states to cooperate in the prosecution of individuals accused of crimes against humanity, and offering refuge to those implicated in such crimes undermines these global commitments.

The challenge of enforcing accountability for enforced disappearances in Bangladesh, as well as the international complicity in offering refuge to alleged perpetrators, raises uncomfortable but necessary questions about global standards of justice.

As the world has increasingly recognized, leaders who commit or enable crimes against humanity must be held responsible—no matter their rank, power, or political connections.

Only through unwavering commitment to the principle of individual responsibility can the international community hope to achieve true justice for the victims of these horrific acts.

—-

Tanjimul Haque and Nusrat Jahan, both graduates of the Law Department at Dhaka University, have recently joined Sadat Sarwat and Associates as Advocates.