Remembering Asad: The student leader whose death triggered the 69’ mass uprising

January 20th comes and goes, marked only by the turn of a calendar page—just another ordinary day for most Bangladeshis. Ask the average person about its significance, and you’ll likely be met with a blank stare. “Is it a special day?” they might ask, genuinely unaware.

This indifference is hardly surprising. In a country where memory is often distorted or forgotten under the weight of time and turmoil, the quiet passage of January 20th feels no different from any other day. But rewind exactly fifty-six years, and you would have gotten a very different answer.

On this day in 1969, a single act of state violence—seemingly isolated at the time—shattered the political status quo and reshaped the future of Bangladesh.

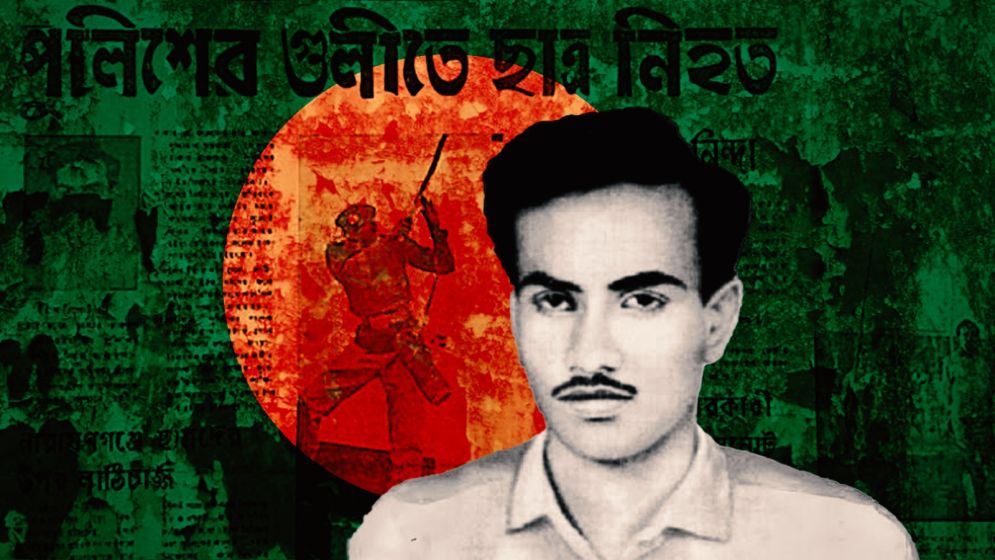

A police bullet took the life of Amanullah Mohammad Asaduzzaman, a student leader whose martyrdom set off a tidal wave of protests. His death didn’t just spark a movement—it ignited a nationwide uprising, one that dismantled Ayub Khan’s decade-long regime and laid the groundwork for Bangladesh’s eventual independence two years later.

In much the same way that the 2024 anti-discrimination movement evolved into a broader rebellion against Hasina’s authoritarian rule, what began in 1969 as a student protest against oppression quickly escalated into a full-scale revolt.

The student leaders' demand for a more just and equitable state became the rallying cry for the entire nation, fueling the struggle for independence that would culminate in the birth of Bangladesh in 1971.

January 20th, once Shaheed Asad Dibosh (Martyr Asad Day), held a deep, collective national significance—a day to honor the sacrifice that changed the course of history.

Yet today, it is all but forgotten.

The significance of that day has faded into the background of a nation preoccupied with more immediate concerns. The name Asaduzzaman is now little more than a distant echo, a mere footnote in the history of a country that has seen its political and social landscape dramatically evolve.

Ingrained political consciousness

Born in the small village of Shibpur, Narsingdi, Asaduzzaman’s life was shaped by a relentless pursuit of principle. A student driven by ideals, Asad’s journey began in 1960 at Shibpur High School, and led him through Jagannath University, Murari Chand College, and eventually the University of Dhaka.

But it was in the trenches of political activism, particularly in his work with the Krishak Samity—a peasant movement in the Narsingdi region aligned with Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani’s National Awami Party—that Asad’s legacy began to take form.

By the time he was shot dead by police in 1969, Asad was in the final stretch of his M.A. in History at Dhaka University. He was not just another student; he was a force within the East Pakistan Students Union (EPSU), where he served as president of the Dhaka Hall unit and general secretary of the Dhaka branch (Menon group).

His involvement in student politics was marked by a singular dedication to the oppressed, a commitment that would ultimately define his martyrdom. “If it weren’t for Asad’s sacrifice, our country’s independence might have been delayed,” says Professor Munir-uz-Zaman, Asad’s immediate younger brother and former principal of Anondomohon College of Mymensingh.

The 1969 uprising, which Asad’s death triggered, is a chapter of history now largely ignored, Zaman pointed out. “The mass upsurge of 1969 has become a neglected footnote,” Zaman remarked. “But without it, the liberation war of 1971 might never have happened.”

By the late 1960s, Ayub Khan’s iron grip on power seemed unshakable. But in the student leaders of East Pakistan, there was a quiet rebellion brewing. As Zaman put it, “Nobody could have imagined that Ayub Khan’s regime, which seemed so unassailable, could be threatened. But it was student leaders like Asad who dared to believe otherwise.”

What began as a student protest in opposition to a repressive military regime soon morphed into a seismic shift in the country’s political landscape. As Zaman notes, the upsurge of 1969 wasn’t merely a spontaneous outburst. It was rooted in deep, systemic injustice, and was a defining moment in Pakistan’s political history.

“You have to understand the context in which the upsurge finally erupted,” he explained, acknowledging the contradictions that fueled the discontent.

Brewing political tensions

Ayub Khan’s economic policies, though they spurred industrial growth in East Pakistan, did little to alleviate the daily suffering of the common people. Poverty, ignorance, and underdevelopment persisted, and the resulting alienation among the Bengalis was undeniable.

The growing economic and political disparity between East and West Pakistan was glaring. As East Pakistani intellectuals began to recognize the stark imbalance in power, they started to rethink the very idea of Pakistan. A new, increasingly vocal narrative began to take hold—one that acknowledged the distinct political and economic realities of the two regions, and demanded change.

The fallout from the 1965 India-Pakistan war only exacerbated the divide. The war had exposed East Pakistan’s military vulnerabilities, and many Bengalis began to question why they should remain under a government that not only underrepresented them but actively sidelined their interests. The central government in West Pakistan, to many, felt more like an oppressor than a partner.

“In this tense and combustible atmosphere, Asaduzzaman’s death would be the spark that ignited the flame of revolution,” Dr Mahbub Ullah, President of Shaheed Asad Parishad, said. It was against this backdrop of disillusionment and unrest that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, president of the Awami League, laid out his now-famous Six-Point Movement in 1966, he pointed out.

The document was a stark demand for greater autonomy, with the ultimate goal of creating a federated state in which East and West Pakistan would coexist on more equal terms. It became, in essence, the blueprint for the constitutional rights of the Bengali people—a vision that would eventually spark the flames of the independence struggle in 1971.

In the winter of 1968 and into early 1969, East Pakistan was awash in strikes and a rising wave of political unrest, much of it sparked by student organizations that fused a call for federalism with fervent assertions of Bengali nationalism.

On January 4, 1969, the Sarbadaliya Chhatra Sangram Parishad (All Parties Student Resistance Council, or SCSP) was officially formed. This broad coalition of student leaders coalesced around a shared set of demands and a unified leadership, a rare moment of convergence in a fractured political environment.

“Their rallying cry was an 11-point charter calling for self-governance in East Pakistan, a demand that would resonate deeply with the nation’s growing sense of disenfranchisement,” said Dr Mahbub Ullah.

Just days after the launch of the SCSP’s bold manifesto on January 8, eight political parties—including the Awami League and the National Awami Party (Muzaffar group)—joined forces, forming the Democratic Action Committee (DAC).

This alliance pushed for a sweeping agenda that included the establishment of a federal government, universal adult suffrage, the immediate withdrawal of the state of emergency, and the release of all political prisoners, most notably Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the imprisoned leader of the Awami League.

“The students, under the umbrella of the DAC, were taking a direct stand against the oppressive regime of Ayub Khan,” Zaman recounted. “Their courageous resistance gave the public the spark they needed to stand up against the injustice they had endured for so long.”

It was a brave and defiant push, not just for political reform, but for a fundamental rethinking of the nation’s structure—one that, as Zaman recalled, carried with it the hopes and frustrations of an entire populace that had long been simmering beneath the surface.

The students’ movement became a formidable force, one that transcended the university campuses and touched the broader discontent of East Pakistan. “This was not just a political struggle; it was a collective outcry from a people who had felt marginalized for years, a cry that Ayub Khan’s iron rule could no longer ignore,” said Dr Mahbub.

“The momentum built rapidly, fueling a movement that was as much about national identity as it was about governance. For the first time, the idea of a unified Bengali political voice seemed not only possible but inevitable,” he added.

On January 20, 1969, a momentous day in East Pakistan's history began under the shade of a banyan tree, at a gathering of student leaders at Dhaka University Batala. Just days earlier, on January 17, the Central Student Action Committee had called for a full shutdown of all educational institutions in the region.

In response, the government invoked Section 144, banning any assembly of more than four people. It was a desperate attempt to quell the growing unrest—but by that point, the political temperature had risen too high to be stifled by legal decrees.

An unsung hero

Asad was not only politically engaged, he was politically aware. He often spoke of martyrdom as a necessary cost of independence, Zaman recalled,“Death wasn’t something he feared.”

“He was, from head to toe, a politically conscious person. He believed true independence wouldn’t come without bloodshed, and he was ready to spill his own blood for the cause.”

Asad understood that his activism made him a target. On the morning of January 20, he told his family goodbye, knowing full well that the day could be his last.

By noon, a sea of nearly ten thousand students, from various colleges across the city, gathered at the University of Dhaka and defied the restrictions of Section 144. The protest quickly escalated into a procession that snaked through the streets, led by Asad.

The students marched toward the PostGraduate Medical College near Chand Khan’s Bridge, where they were met with a violent police response. For nearly an hour, the clash between the protesters and law enforcement raged on. Asad, determined to keep the momentum going, tried to steer the procession toward the city center, near Dhaka Hall. But then, tragedy struck.

In the midst of the chaos, a police officer named Bahauddin fired a shot that struck Asad, killing him instantly. His death would mark a turning point in the history of the student movement and in the wider struggle for independence.

In an effort to downplay the killing, the provincial government, led by Governor Monem Khan, attempted to cover up the truth. A press release circulated, labelling Asad as a "terrorist" in an attempt to justify his death. But the government’s narrative quickly unraveled in the face of mass outrage.

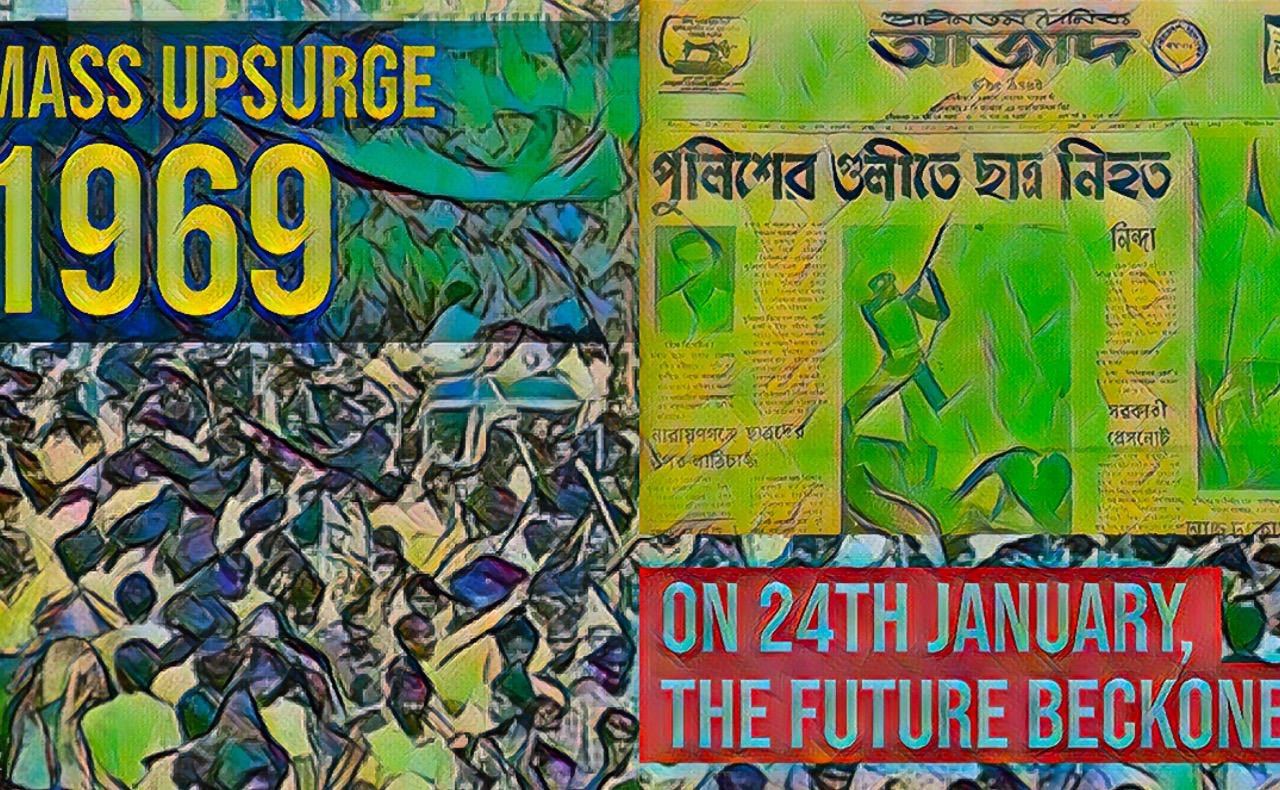

What followed was an unprecedented outpouring of grief and anger. Students, galvanized by Asad's martyrdom, flooded Dhaka Medical College, where his body was taken. A mourning procession, swelling by the minute, stretched two miles long, with women at the forefront.

As the procession wound through the city, ordinary citizens—workers, vendors, and the general public—joined in. It was no longer just a student movement; it had become a mass uprising. The procession ultimately ended at the Shaheed Minar, a national symbol of resistance, where the mourners gathered to honor Asad.

In the wake of his death, the Central Student Action Committee declared three days of mourning across East Pakistan. The following days saw more hartals (strikes) and protests, culminating on January 24, when students once again clashed with police.

By then, the situation had spiraled beyond the control of the government. Monem Khan's repressive measures failed to suppress the public outcry, and, as Zaman observed, "The regime of Ayub Khan was crumbling."

Asad’s death transformed the 1969 movement into a full-blown uprising. In the days that followed, people, by their own volition, began to erase symbols of the oppressive regime. In many places, the nameplates bearing Ayub Khan’s name were replaced with Asad’s.

The iconic Ayub Gate was renamed Asad Gate, and Ayub Avenue became Asad Avenue. “Since then, the name of Asad has become synonymous with the struggle against repression,” Zaman reflected.

A relentless rebel

Dr. NM Nuruzzaman, a former director at the Directorate General of Health Services and another one of Asad’s brothers, paints a portrait of Asad that transcends his role as a student leader.

For him, Asad was not just a political organizer but a deeply committed social worker, one whose life was shaped by a profound sense of empathy and responsibility for the marginalized.

“Whenever Asad came back to the village,” Nuruzzaman recalled, “he never stayed at home. Instead, he would go directly to the homes of poor farmers, sit with them, eat with them, and, most importantly, talk to them about their rights.”

In the rural heartlands of Shibpur and its neighboring regions, Asad played a pivotal role in building a powerful peasant movement that became central to his political vision. "The strength of the peasant movement he led was so formidable that even government officials under Monem Khan's administration were afraid to venture near the main roads around Shibpur and Monohardi," recalled Nuruzzaman.

“Asad believed that democracy was the only true path to the liberation of our people,” said Nuruzzaman. “But he also understood that without educating the masses, real change would never come.”

His vision was one of empowerment—of giving voice to those long silenced by systemic poverty and oppression. And in his view, the first step toward this transformation was education.

"He insisted that primary education should be free and compulsory," Nuruzzaman explained, reflecting on his brother's forward-thinking approach.

In pursuit of this, Asad helped establish a night school in Shibpur, one that was open to the laborers and impoverished farmers in the area. Asad also had an acute awareness of the need for a political movement that was ideologically mature and revolutionary in its vision.

In 1968, Asad had written in his diary about the necessity of creating a study circle focused on the politics of the “Sarbahara”—the oppressed, landless class.

He understood that a movement for true liberation would need both intellectual rigor and revolutionary action. To that end, Asad was one of the key figures in the Coordination Committee of the Communist Revolutionaries of East Bengal, a group dedicated to the creation of a sovereign, exploitation-free state.

“In many ways, Asad’s contributions during 1969 and his broader political vision cannot be fully captured by the pages of history,” Nuruzzaman mused. “He envisioned a nation free from oppression and exploitation, a cause for which he gave his life. And the truth is, he deserves so much more than the hollow homage we pay him today.”

There was a deep sadness in his voice, an acknowledgment of the gap between the recognition Asad had earned and the one he ultimately received. “The respect he deserves is still due,” he added quietly.

---

Faisal Mahmud is a nephew of Shaheed Asad