Rebuilding national unity in post-Awami-fascist Bangladesh is a massive uphill task

In an era marked by profound societal shifts, the battle against authoritarianism faces growing challenges, particularly when confronted with a range of sophisticated strategic assaults.

Eminent Indian thinker and writer Ashis Nandy highlights how such pressures risk eroding one's very sense of identity. The fight against fascism, he warns, loses its potency when the internal resolve of a society falters.

During the Awami League’s rule, this internal fortitude seemed to dissipate, allowing a form of fascism to permeate the nation. The socialization of fascism during this period didn’t merely come from above; it seeped into the very fabric of everyday life.

Analyzing why so many were drawn to accept such a regime reveals a complex web of motivations, but five key factors stand out.

First, there was widespread political ignorance, a lack of awareness about the true nature of the regime. Second, many turned a blind eye to the immorality and brute force that defined the Awami League's tactics.

Third, personal or familial greed played a significant role, as individuals sought financial gain under the regime’s patronage. Fourth, the party’s effective propaganda, steeped in false historical narratives and distortions, swayed the public’s perception.

Finally, many were not genuine supporters but rather opportunistic followers, feigning allegiance to avoid social or political repercussions.

The Awami League, as some argue, was never a political party in the traditional sense. It functioned more as a syndicate, one that perpetuated the exploitation of Bangladesh, using power to loot and control.

Fascism, in this light, isn't a legitimate ideology but the creation of a vast, oppressive apparatus built on criminality. If we are to view the Awami League as fascist, then the idea of it being a legitimate political entity vanishes.

There’s a fundamental contradiction in claiming to oppose fascism while simultaneously supporting the right of a fascist party to engage in politics. To build a society truly free from authoritarian rule, one must, at the very least, consider a future without the Awami League's presence in political life.

Without this shift, any meaningful political discourse remains impossible. This doesn’t imply that banning a political party is the ultimate solution—though such a move might bring momentary relief—but it does underscore a larger problem: our collective failure to recognize and confront fascism effectively.

How fascism resurges under the guise

of equality

As we look to the future, the question of how to address the Awami League will shape the trajectory of Bangladeshi politics. The struggle against authoritarianism must be defined not by fleeting actions or symbolic gestures but by a strategic, long-term commitment to safeguarding true democratic values.

It is essential to recognize that all fascist regimes, regardless of the particular context, present themselves as champions of democracy, promising to protect people's rights and securing power through popular support.

The grave danger lies in permitting such ideologies to persist under the guise of democratic legitimacy. As philosopher Carl Schmitt argued, defending democracy doesn’t require an endless policy of tolerance—it demands clarity and resolve in the face of threats to its very existence.

The future of Bangladesh’s political landscape will depend on how resolutely it confronts this uncomfortable reality.

Schmitt’s exploration of parliamentary democracy in Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy presents a stark warning: “Every actual democracy rests on the principle that not only are equals equal but unequals will not be treated equally.”

In other words, democracy doesn’t promise equality for all, but instead demands a form of homogeneity. This means that, when necessary, heterogeneity—the existence of differences—must be eradicated.

In Schmitt's view, treating everyone equally is a misinterpretation of democracy's true function. It’s not about leveling the playing field for all, but about ensuring that rights are respected, while differences remain acknowledged and addressed. This tension lies at the heart of the struggle to build a genuine democratic society.

The promise of universal equality, especially as espoused by movements calling for "equality for all," is not only unrealistic but also dangerous. Rather than aiming for equality in a superficial sense, democracy thrives on the establishment of rights—real, enforceable rights that ensure every citizen's dignity is protected.

What is more dangerous, however, is when this promise of equality begins to mirror fascist rhetoric. Political movements that claim to deliver equality often hide authoritarian undercurrents beneath their appeals, undermining democracy in the process.

A more honest approach would advocate for the establishment of rights—not equality, but rights—guaranteeing individuals the space to progress on their own terms. If rights are preserved, the nation will move forward collectively.

The rule of law must be applied impartially, and the values of democracy should be embedded in both individuals and institutions.

Deeply entrenched problems

In Bangladesh, the persistence of the Awami League’s influence reveals how deeply fascist ideologies can entrench themselves within political and societal systems. Far from being a traditional political party, the Awami League has operated like a syndicate, one that uses political power for looting and control.

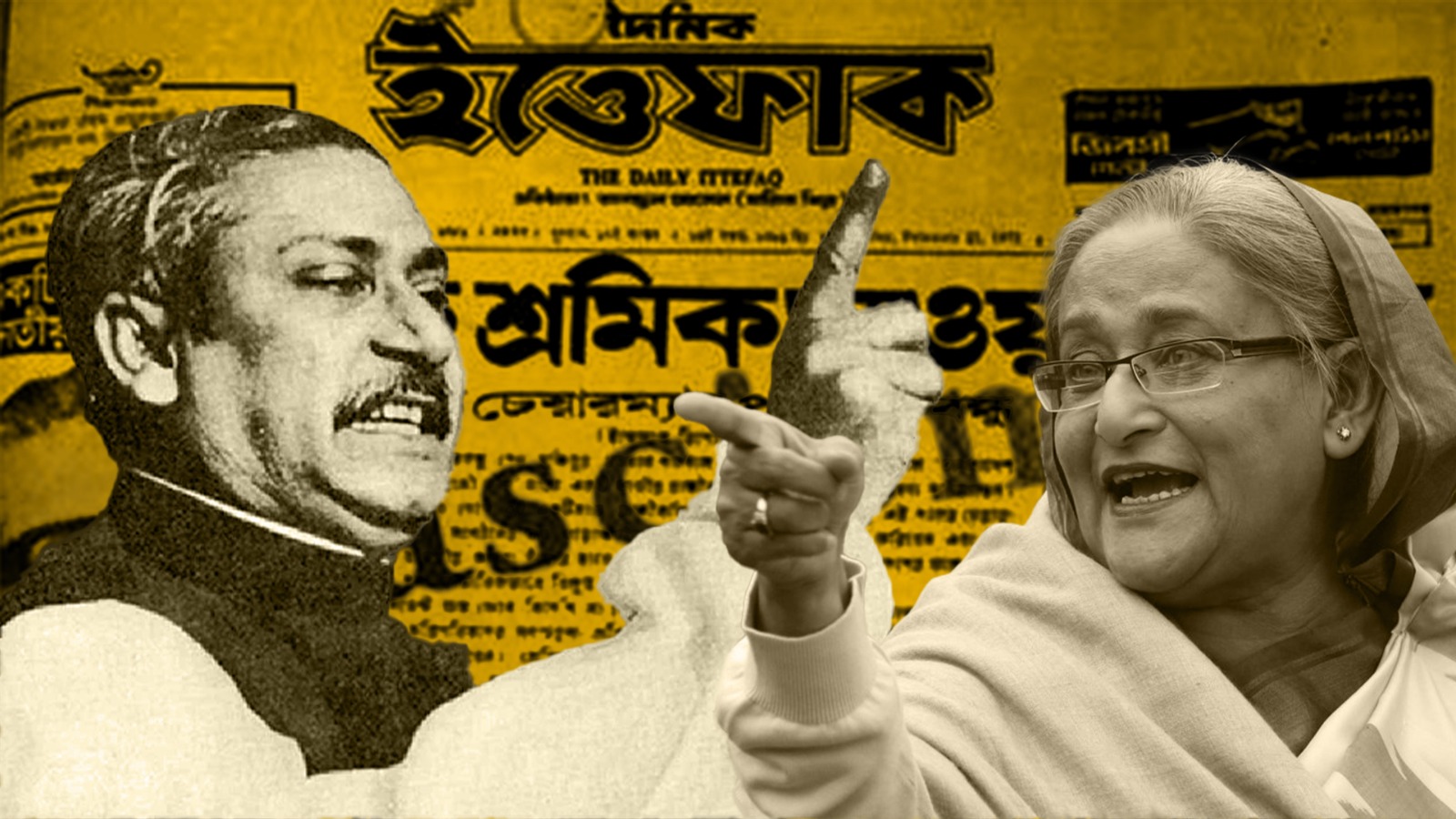

Its fascist tendencies were apparent from the earliest days of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s rule, but it is under the current regime that these tendencies have reached their most extreme.

Over the past 15 years, the party has engaged in brutal acts of repression, silencing opposition through violence, intimidation, and mass atrocities. The July uprising, where civilians—including children and students—were massacred, shocked the world and briefly brought down the regime.

However, despite their expulsion, the fascist structures underpinning the Awami League remain intact. These structures continue to haunt the nation, preventing real political change.

As the party’s core remains strong, the question of legitimacy looms over Bangladesh’s political future. With elections approaching, many are asking whether a vote without the Awami League would be valid.

Those who believe a democratic process must include the Awami League fail to grasp the full consequences of such an allowance. Enabling fascist forces to participate in the democratic process is tantamount to inviting their return—more brutal and powerful than before.

No political party can, with good conscience, accept the Awami League’s return to politics until those responsible for the bloodshed face justice.

Yet, doubts abound about whether this justice will ever materialize, as the pace of legal proceedings and accountability appears slow and uneven.

The deeper challenge, however, is societal healing. The trauma inflicted by years of fascist rule has left scars, making it difficult for citizens to voice their opinions freely. Many fear the resurgence of the very forces that suppressed them for so long.

Restoring the collective strength of the people will be the ultimate test for Bangladesh’s future. Without a reckoning with the Awami League’s legacy, national unity will remain out of reach.

True democracy, after all, cannot exist where fascism lingers in the shadows, ready to strike again. The task, then, is not just to defeat fascism in theory, but to exorcise its presence from the nation’s very fabric.

Umberto Eco once said, "Believing in something false is more dangerous than believing in nothing at all."

This insight resonates deeply when considering the Awami League, a political entity that, far from being a conventional party, represents an ideological force with a singular mission: to entrench fascism whenever it gains power.

This was evident during both Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s and Sheikh Hasina’s regimes. The crimes committed under their leadership, especially mass killings, must not be overlooked.

Failing to hold the perpetrators accountable would not only be an injustice to the victims but also complicit in the suffering of countless martyrs and the thousands who were left physically and emotionally scarred.

Yet the question remains: what about those who continue to champion this fascist ideology?

The danger of

false ideologies

Despite a mass uprising that temporarily stripped the Awami League of its power, many who once stood firmly behind the party's oppressive politics are still active in society, whether in politics, business, or the media.

Some leaders have fled, others are in hiding or facing prosecution, but the larger question revolves around the supporters of the regime—the people who quietly sustained its power, whether by donating funds, propagating its beliefs, or even just turning a blind eye to its brutal actions.

While not all of them directly participated in violence, they lent the ideological and financial support that enabled it. How should they be treated?

Their crimes, though less visible, are not without consequence. Will these individuals, many of whom remain loyal to the Awami League’s principles, continue to thrive in society?

Will they simply shift their allegiances to other parties, subtly reinforcing the same fascist values? For the families of martyrs and the injured, seeing these individuals remain influential will be a painful reminder that the uprising’s spirit of justice has yet to be fully realized.

Can we truly claim to have emerged from this dark chapter if those who perpetuated the ideology of the Awami League can blend back into society without consequence?

There is a difference between the active perpetrators—the ones who took to the streets and carried out violence on behalf of the Awami League—and those who merely subscribed to its ideology.

Over the years, the BNP and Jamaat were demonized, with people arrested and harassed under false pretenses. But should the same tactic now be used against Awami League supporters?

If the answer is yes, then it raises serious questions about what we mean by justice and change. Are we simply swapping one set of false narratives for another, or are we truly building a new, inclusive political landscape?

While believing in a fraudulent ideology may not be a direct crime, it is still a grave wrong. People must be allowed the opportunity to recognize their mistakes and correct them, but if they continue to live in denial—clinging to lies—national unity will remain an impossible dream.

History teaches us that victims of oppression can become the perpetrators of violence. The cycle of creating victims must end, and for this, tangible, effective actions are necessary.

The path forward lies in not just holding the guilty accountable, but in ensuring that the ideological forces that enabled such tyranny are thoroughly discredited and dismantled. Only then can true reconciliation begin.

The path to healing and national

reconciliation

Addressing the deep-rooted fascism in Bangladesh requires more than just criminal justice—it demands a cultural and ideological shift. When Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was assassinated in 1975, few could predict that, 25 years later, his daughter Sheikh Hasina would return to power, reflecting how firmly Awami fascism had taken hold of the country's political landscape.

This ideology has ingrained itself not just in the state apparatus but in the very character and behavior of many people. The Awami League, once hailed as the mainstream political force, has become almost synonymous with the nation’s political identity.

As a result, the Awami League’s influence permeates every level of society. Despite efforts by other political parties to oppose it, none have effectively countered the deep moral decay that the Awami League’s dominance has fostered.

This political party is no longer just a political entity—it has evolved into a near-inevitable presence in Bangladesh. Without a concerted effort to ideologically and culturally challenge the Awami League and render it powerless, no political opposition can truly break free from its shadow.

Its deep entanglement in society and its corrupting influence on individual character mean its relevance will persist until actively confronted.

The Awami League has reshaped politics as a business for the morally compromised, rendering decent individuals powerless against its hold. As long as this pervasive influence goes unchallenged, Bangladesh will struggle to form a morally strong political community.

Societies built on self-deception, like Bangladesh today, never establish themselves as truly honorable in the eyes of the world. The core issue at the heart of Bangladesh's current disorder is the collapse of its collective moral compass, a collapse that was accelerated by the fascist practices of the Awami League.

In this climate, wrongdoing is no longer seen as a betrayal but as a right. People not only lie to gain small advantages, but they also believe their own lies, killing their inner integrity. Living in such a state, they become like the walking dead—devoid of historical or existential potential.

If this moral degradation is not addressed and eradicated from the Bangladeshi populace, the future of the country as a collective society remains bleak.

This is why we must look beyond punishment alone and consider the example of South Africa, where the "Truth and Reconciliation Commission" was established in 1996 to address the atrocities committed during apartheid.

What can a Truth and Reconciliation

Commission do?

Inspired by the Nuremberg Trials, the South African commission focused not only on prosecution but on a broader process of forgiveness and societal healing. Its goal was not merely to punish but to restore humanity and unity within a fractured society.

Though each country’s circumstances differ, Bangladesh must adopt a similar process of healing.

Just as the Allies undertook a five-year denazification process in Germany after World War II, Bangladesh must prioritize the long-term effort of de-Awami or de-Awamification—a term that encompasses both the removal of Awami League’s ideological influence and the cultural transformation needed to build a new, morally upright society.

This task is vast and complex, but it is essential for the nation’s progress. Even if this process spans decades, it must be pursued relentlessly.

In 2023, the BNP and allied parties presented a 31-point reform agenda aimed at restructuring the state. Point 13 called for the establishment of rule of law at every level and the restoration of human values and dignity. It emphasized ending the culture of abductions, extrajudicial killings, torture, and other inhumane practices.

The agenda also proposed that all those directly or indirectly responsible for crimes over the past 15 years be brought to justice. A commission has already been suggested to handle these matters, and it includes accountability for indirect perpetrators.

After significant bloodshed and the mass uprising, this need for justice has only become more urgent.

If the current government, alongside all political parties and civil society, can initiate this effort, it would lay the foundation for a long-term process of truth, confession, and reconciliation.

While such an endeavor cannot be completed immediately, the momentum it creates can be carried forward by those who come to power in the future. This commission, inspired by the models of South Africa and post-Nazi Germany, will be essential in ensuring justice and promoting national healing.

Only by confronting the past and dismantling the fascist forces that have shaped Bangladesh’s political and social fabric can the nation hope to rebuild and move forward with integrity.

The need for a national de-Awami

effort

In Bangladesh's journey toward nation-building, one of the most harmful lessons we’ve learned from the Awami League is their misguided approach to “friendship.”

For decades, they have emphasized the notion of "friendly states," yet a state’s foundation is not built on unconditional friendships but on a clear-eyed understanding of potential threats.

This doesn’t imply fostering enmity, but rather recognizing dangers to sovereignty and national interests. Relations between countries should be based on mutual respect and cooperation, not on presumptions of friendship that risk undermining a nation's true needs and goals.

The same principle applies within the country’s borders. A unified political front is necessary to defend Bangladesh’s sovereignty against any internal threats. The Awami League, however, has consistently acted as an anti-Bangladesh force, undermining the nation's democratic ideals.

The bloody uprising that arose in response to their actions revealed the Awami League as a common enemy, a realization that should guide our approach moving forward.

Without uprooting the ideology and culture the Awami League has propagated, authoritarianism will continue to thrive. As the saying goes, you cannot cleanse dirt with more dirt.

To truly establish a collective moral spirit in Bangladesh, we must confront this shared enemy in all political, social, and cultural spheres. This effort will solidify the spirit of the uprising and ensure its long-term impact.

Allowing the Awami League to remain politically active would keep the nation trapped in a tribal-level political struggle. Only by clearing the political space of the Awami League can we engage in meaningful discussions about the relationship between the state and its citizens.

This process requires a comprehensive national project aimed at de-Awami—a concerted effort to dismantle the ideological and cultural grip the Awami League has over society.

Many individuals who once aligned with the Awami League for strategic reasons have since compromised their moral integrity. Even those who played pivotal roles in the uprising must now reflect on whether their actions, aimed at strategy rather than principle, have enabled the persistence of fascism.

In essence, any relationship with the Awami League requires both confession and accountability. We must ensure that those who once supported the League face the consequences of their involvement in this dark chapter of history.

The need for a Justice Commission

A key component of this national effort must be the creation of a Justice Commission, supported by civil society. This commission should involve the families of those who were killed, disappeared, or injured under the Awami League regime.

Its scope will extend beyond the July uprising to address all forms of injustice committed during their time in power.

The commission will work to identify actual criminals, document crimes, and encourage confessions from those who, knowingly or unknowingly, supported the regime’s fascist ideology. This initiative must be rolled out across the nation, engaging all sectors of society and government to ensure transparency and accountability.

While South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission faced its own set of challenges, we must be careful not to place the burden of forgiveness on the victims. We do not intend to grant any one person the authority to forgive the perpetrators of these crimes.

Instead, the aim is to ensure the protection of the accused's rights while providing an opportunity for those who supported the regime to expose the real criminals and confess their role.

This process can strengthen social unity, heal national wounds, and restore a sense of shared moral integrity within the population.

For this effort to succeed, the government must provide unwavering support. All political parties, civil society organizations, and experts—both national and international—must come together.

We could seek assistance from global bodies such as the United Nations and countries like Canada, which have experience in handling similar processes. Additionally, existing commissions could be integrated into this initiative to amplify its reach and effectiveness.

This process must engage every level of society—from government institutions to neighborhoods and individual households.

The task ahead will take time—likely three to four years—but it is a vital and necessary one. Soft Awami League supporters, opposition parties nurtured by fascism like the National Party, and any individuals or organizations that have allied with the League must all be held accountable.

This effort to restore justice and integrity to Bangladesh is a long-term commitment, but it is a commitment that we must make for the future of our nation.

Only through this comprehensive de-Awami project can we hope to rebuild Bangladesh as a country rooted in democratic rights, moral strength, and national unity.

The path of truth, justice, and

national renewal

The journey toward truth, justice, and societal reconstruction in Bangladesh is not just an effort to address past wrongs, but a transformative process with the potential to reshape the nation’s future.

The primary aim is clear: we must deliver justice to the deceased and injured, ensuring that criminals are documented and held accountable.

As this process unfolds, the trauma inflicted on society will gradually fade, and the moral rot fostered by fascism will be rooted out from the collective psyche. The victories of the uprising will be preserved, and the fear of a return of authoritarianism—disguised or otherwise—will finally be extinguished.

But perhaps the most significant achievement will be the cultivation of public awareness. A nation’s political future depends on the consciousness of its people, and this process will lay the groundwork for a more politically astute society.

When individuals see the consequences of aligning with a fascist ideology—whether through criminal conviction or realization of their past mistakes—it will foster a culture of critical thought.

This newly awakened political consciousness will make it far less likely for dangerous ideologies to take root in the future. Democracy can only thrive when the people are empowered to think critically, assess ideologies, and reject those that undermine freedom and justice.

In addition to this cultural shift, the process will eradicate the dormant seeds of Awami League fascism from society. People will come to understand the true nature of political movements, avoiding the traps of false promises and deceptive ideologies.

The days of idolizing figures for political gain or betraying one’s conscience in exchange for personal benefit will end. Compromise with lies will no longer be tolerated, and Bangladesh will regain its inner strength.

However, this journey of societal purification will not be easy, especially for those who once supported the Awami League. Many of its followers are beginning to realize that their leader, who fled at the height of the crisis, deceived them.

The recognition of this betrayal will challenge their long-held beliefs and emotional attachments to the party, which may have once seemed a symbol of liberation, but now stands as a monument to violence and oppression.

Confronting brutal truth

As Ashis Nandy insightfully observed, “The ideas that once symbolized liberation later open the path to violence and exploitation.” Awami League supporters must come to terms with this reality.

They must confront the brutal truth that their allegiance to the party, especially in the wake of its actions during the recent massacres, was misplaced.

To move forward, those who once supported the Awami League must break free from the shackles of this delusion and actively participate in the process of rebuilding Bangladesh.

This process can be transformative for them as well—perhaps even symbolic. Let it be a celebratory moment, a moment where individuals publicly renounce their past allegiances, perhaps even symbolically washing away their connection to a party that has led the nation astray.

They should assist in bringing perpetrators to justice and, in doing so, help heal a fractured society.

The goal here is not to target any individual or political party but to prioritize the nation’s collective well-being. This is an opportunity for all to engage in the healing process, to cast aside falsehoods, and to join together in the common cause of national renewal.

Those who actively participate in this effort will be rewarded with a certificate from the commission, symbolizing their renewed commitment to the people and the nation.

For those who refuse to embrace the truth, however, the consequences may be severe. If the pursuit of truth leads to danger for those who cling to lies, then there will be little left to do but mourn the lost opportunities for reconciliation and growth.

But as long as we remain committed to the values of justice and truth, Bangladesh can emerge from its troubled past with a renewed sense of unity and purpose.

The task before us is clear: to expel fascist ideologies from the fabric of society and restore a moral, democratic, and unified nation. This is not just an urgent need, but an opportunity to forge a better future for all.

—-

Rezaul Karim Rony is a writer and thinker. He is the editor of Joban magazine