NYT article about the rise of Islamist hardliners is not wrong. It’s not right either

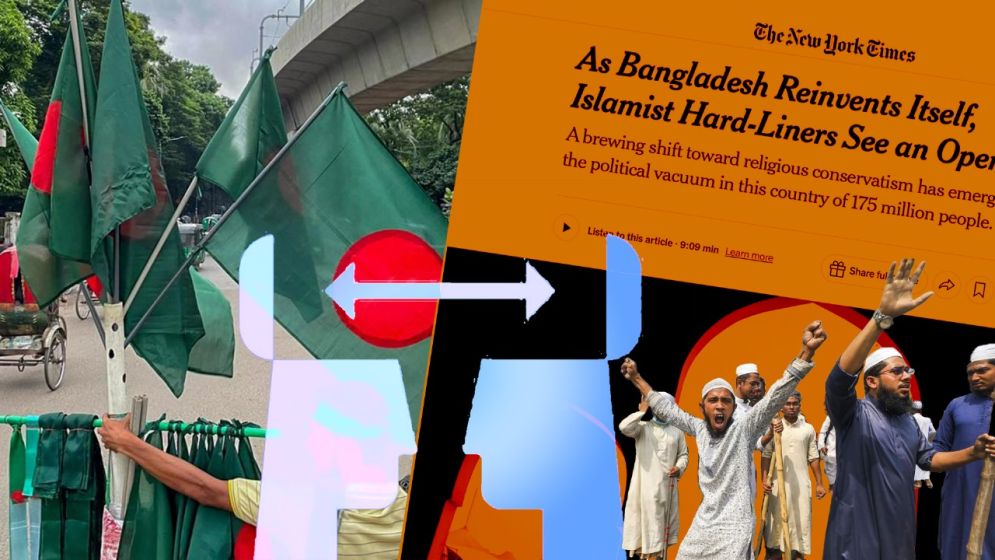

On April 1, the New York Times, widely regarded as the most influential newspapers in the world, published an article suggesting that Bangladesh, following the ousting of autocratic leader Sheikh Hasina, is inadvertently creating more space for Islamist hardliners.

While this one-line summary might seem accurate at first glance–especially in today’s era where we condense everything into bite-sized pieces–the nuance of the situation is much more complex.

Like the publication date–April 1st–such a simplistic view can easily mislead and oversimplify what’s actually unfolding in Bangladesh.

This was the sentiment expressed by the Chief Advisor's Press Wing, led by veteran journalist Shafiqul Alam. His response received praise from many, but also drew criticism.

This is because the Bangladeshi public has grown weary of the "smoke and mirrors" media tactics employed by the government-controlled press during Hasina's rule, which would often downplay international criticism by emphasizing the government's "great achievements."

Given this history, the backlash against the Chief Advisor’s Press Wing is understandable.

However, the reality is that the New York Times article, penned by Mujib Mashal and Saif Hasnath, is one of those pieces that can be both right and wrong at the same time. This is often the case with international outlets that, in their attempt to distill complex issues into concise narratives, end up trimming away key nuances.

When dealing with sensitive topics like religion–especially Islam, the most political of them all–those nuances become even more crucial. Missing them can lead to significant misinterpretation of the situation.

“Secular” government and “empowered”

Islamists

Currently, Bangladesh is led by Dr. Muhammad Yunus, arguably the most internationally renowned Bangladeshi figure of all time. He is a secular figure and a staunch advocate for women’s rights, with his microcredit initiative serving as one of the most empowering forces for women over the past four decades.

His cabinet, largely composed of technocrats, is possibly the most secular in the country’s history. One of the two student leaders now in the cabinet, Mahfuj Alam, who has long been wrongly accused of being linked to a banned Islamist group, has consistently made secular statements and posted on social media, earning backlash from far-right groups.

This "secular" government, despite facing significant opposition from a bureaucracy and police force that were compromised under Hasina's 15-year rule, is doing everything it can to redirect the country's economy and politics toward a more stable, sustainable future.

This is no small task, given the mess the interim government inherited.

While managing the economy might be somewhat more straightforward with figures like Salehuddin Ahmed, Ahsan Mansur, Ashik Chowdhury, and Sheikh Bashir Uddin at the helm, politics is far more complicated.

As the New York Times article pointed out, “Islamist hard-liners see an opening,” and indeed, the ultra-right-wing Islamists have identified a political opportunity to empower themselves to the point where they could potentially take power through a popular mandate.

This is no longer an entirely implausible scenario.

The largest Islamist party in Bangladesh, Jamaat-e-Islami, traditionally held a voter base of around 5%-8% before the July uprising. However, it is now estimated to be between 15%-20%. While there’s no comprehensive polling data to definitively confirm this, a survey conducted by the independent agency Innovision Consulting suggests this range.

If we consider online polls conducted by popular YouTubers with millions of followers—though these polls are almost certainly skewed due to the specific demographics of their audiences—this figure could even double.

Add in the online engagement from hardline Islamist activists, ordinary citizens, and bots, and it’s possible to imagine a scenario where Jamaat-e-Islami could find itself in power.

Jamaat-e-Islami is not alone; there are 13 other registered Islamist parties, and their popularity is on the rise, particularly in rural and fringe areas.

These parties not only have influence over the largest educational system in the country, the Kawmi Madrasah, but they also provide support to underprivileged communities. Their primary sources of entertainment and information come from YouTube videos of Islamist preachers.

Under Sheikh Hasina’s autocratic rule, these Islamist political parties were suppressed through a combination of force and strategic vilification.

In the case of Jamaat-e-Islami, Hasina used the judiciary to convict top leaders—often with questionable evidence—linking them to war crimes during the country’s liberation struggle.

Additionally, enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and lengthy prison sentences kept them weakened and subdued.

Against other prominent Islamist preachers and parties, Hasina relied on long prison sentences based on fabricated charges. Simultaneously, she employed a divide-and-rule strategy to win the favor of certain large Islamist groups, like Hefazat-e-Islam, pitting them against each other so they would be too distracted to focus on national politics.

This tactic benefited Hasina's government for over a decade, but it deeply damaged the fabric of the country.

Pent up anger and frustrations

Bangladesh cannot exist in isolation, and Islam—the country’s primary religion—is constantly evolving. When India, which surrounds Bangladesh on three sides, effectively turned into a Hindu-dominated nation, relegating 200 million Muslims to second-class citizens, it impacted the Muslim population in Bangladesh.

Similarly, when over a million Rohingyas were displaced from neighboring Myanmar and the global community largely ignored their plight as a stateless, oppressed Muslim group, it resonated with Bangladeshi Muslims. When a genocide continues in Gaza and the world remains silent, it also affects the Muslim population in Bangladesh.

In post-August 5 Bangladesh, where the largely Muslim population in rural areas has regained its political agency, the accumulated anger and frustration–towards India, and the world's indifference to the Gaza genocide–have erupted like a shaken soda can, spilling out into the public.

Yes, the incidents mentioned in the NYT article are factually accurate. Islamist hardliners did try to stop a women's football match, they did force the police to release a man who had harassed a woman for not covering her hair, and at a rally in Dhaka, they threatened to take matters into their own hands and execute anyone who disrespected Islam unless the government imposed the death penalty.

But what would this interim government do? Would it follow Hasina’s example and adopt a hardline stance against the Islamists, dehumanizing them, which has proven both unethical and ineffective since August 5? In the new Bangladesh 2.0, why should anyone be afraid to speak their mind?

The interim government has taken action though. It awarded the Ekushey Padak–the second-highest civilian honor–to the national women’s football team. It ensured the university where the harasser worked suspended him from his position.

It also made it clear it had no intention of passing laws imposing the death penalty for disrespecting Islam.

And while the interim government took these steps, the hardline Islamists did nothing significant. They shifted focus to other issues, but they did not pose any security threat.

Bangladesh is a largely homogeneous country, and there is little space for fostering extremism along communal lines. The level of tolerance and humanity among its people is evident. This was particularly clear after August 5, when many feared a violent uprising on a revolutionary scale. In reality, the death toll was under 2,000.

So, while the NYT article is right in saying that Islamist hardliners see an opportunity in post-Hasina Bangladesh, it is at the same time wrong in equating or at least alluding to equating Bangladesh to its extreme South Asian neighbors.

It also provides ammunition for India to continue vilifying Bangladesh’s interim government, which would only complicate matters further.

—-