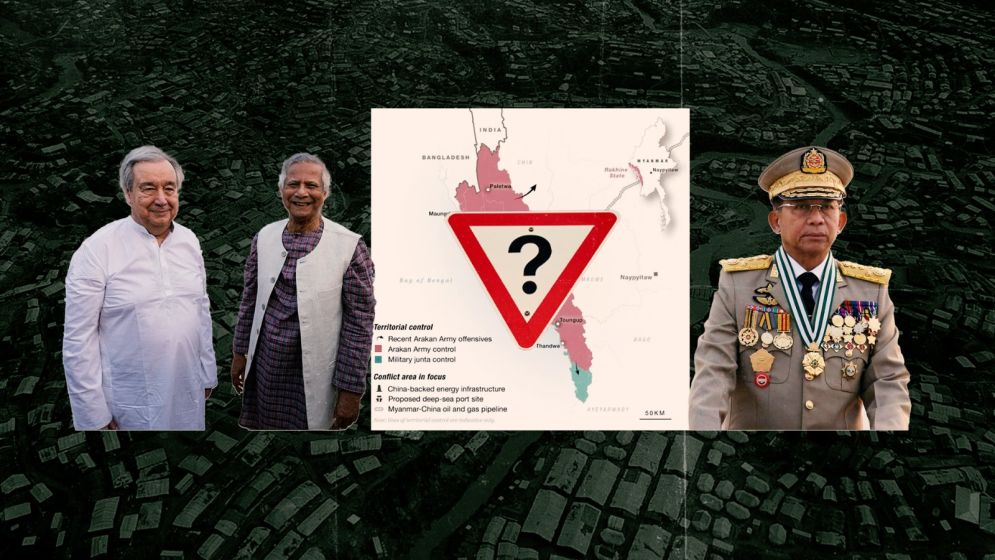

Why the proposed ‘Humanitarian Corridor’ demands transparency, not secrecy

In a move hailed as a humanitarian gesture but mired in ambiguity, the Bangladeshi government has announced that it will “conditionally” agree, in principle, to the establishment of a humanitarian corridor through its territory into Myanmar’s Rakhine state.

The announcement, made by the Foreign Affairs Advisor to the interim government, Md Touhid Hossain, came in response to mounting calls from the United Nations and other human rights organizations.

But beneath the veneer of international cooperation lies a troubling lack of clarity, coordination, and coherence. The decision, instead of offering hope, has sparked confusion– and for good reason.

The government has offered no concrete plan, no operational blueprint, and no clarity on what conditions they have attached to this agreement. In a region already steeped in geopolitical tension and mistrust, vagueness seems not just mere carelessness–it’s dangerous.

At the heart of the issue lies the very concept of a “humanitarian corridor,” a term used liberally but explained sparingly. Typically, such corridors are demilitarized pathways established to deliver aid or provide safe passage for civilians trapped in conflict zones.

They are complex logistical and diplomatic undertakings, often overseen by neutral entities like the UN or the Red Cross. So far, there is no indication of who, if anyone, would be in charge of the proposed corridor through Bangladesh.

Even more troubling are the geographical and procedural black holes in the plan. Will the corridor cut across Bangladeshi soil only, or will it extend into Arakan (Rakhine)? Is it intended purely for aid transport, or will it function as an escape route for civilians?

How much sovereignty will Bangladesh relinquish over this territory, and to whom? These are the very foundations upon which such a corridor must stand.

Security analysts are understandably baffled. If the primary aim is simply to move relief into Rakhine, then why not use the Sittwe Port– a strategically located and logistically capable hub within Myanmar?

Sittwe, notably, is the site of major Chinese and Indian infrastructure investments. Then the question naturally arises whether Dhaka’s maneuver is a humanitarian effort or a geopolitical gambit?

Adding to the opacity is a discordant narrative coming from inside the government. While the Foreign Affairs Advisor claims a conditional agreement has been reached, the Chief Advisor’s press secretary, Shafiqul Alam, insists there have been no formal discussions with the UN.

That assertion strains credulity. Just two

months ago, Khalilur Rahman–Chief Advisor’s High Representative for Rohingya

affairs–held talks with the UN Secretary-General on this very subject. António

Guterres visited Bangladesh in March. If these were not discussions, then what

were they? Diplomatic small talk?

The region and the geopolitical context

The Arakan region–historically neglected and perpetually volatile–has now become the latest arena for great power contestation. China, Russia, India, and the United States all have strategic stakes in the area, turning it into a geopolitical flashpoint.

In such a combustible environment, any initiative–humanitarian or otherwise–demands robust multilateral diplomacy. Yet, the Bangladeshi government's approach to the proposed humanitarian corridor has been disturbingly unilateral and shrouded in strategic vagueness.

According to Khalilur Rahman, Dhaka has coordinated with Naypyidaw before agreeing to the corridor plan. But this raises more questions than it answers: Have the necessary consultations with China and India–both deeply embedded in Myanmar’s infrastructure and energy sectors–taken place? Has Washington also been formally briefed?

There are indications, however, that the Americans are watching closely–and perhaps even positioning themselves for a more active role. In March, shortly after the UN Secretary-General’s visit, two high-level U.S. military delegations arrived in Dhaka.

The first, led by Lt. Col. Mikhail E. D. Michii, the U.S. Embassy’s Military Attaché, met with Brigadier General Md. Alimul Amin, Director General of Military Operations. The second, more high-profile visit came from Lieutenant General Joel B. Vowell, Deputy Commanding General of the U.S. Army Pacific and a seasoned Iraq and Afghanistan war strategist.

Officially, these meetings were about “border security,” a phrase often used as diplomatic camouflage. But behind the scenes, analysts in Dhaka suspect a more complex calculus.

With the Arakan Army reportedly gearing up for full territorial control of Rakhine, the need to keep its supply routes open has become a tactical priority– one that may require, or at least benefit from, quiet cooperation with regional military forces, including Bangladesh’s.

Some sources suggest that the American delegations were not merely visiting–they were assessing.

April brought further movement. Two top officials from the U.S. State Department and the U.S. Ambassador to Myanmar traveled to Bangladesh, where the agenda included not just the Rohingya crisis but broader strategic concerns.

One Foreign Ministry official described the shifting Myanmar landscape as a direct challenge to America’s Indo-Pacific Strategy–a telling admission that Washington sees this corridor not just through a humanitarian lens, but as a node in a much larger strategic network.

The stakes of this shadow diplomacy only deepened with reports that the Director General of Bangladesh’s military intelligence agency, DGFI, recently met with the CIA chief to discuss developments in Myanmar and the evolving regional posture.

All of this makes one thing clear: The

proposed humanitarian corridor is definitely not just a logistics route for

aid– it is now a fault line in a militarized, multi-actor regional struggle.

And yet, the Bangladeshi government persists in treating it as a mere

administrative matter, devoid of strategy or transparency.

What’s the real motive of Dhaka?

If Dhaka has indeed entered into quiet coordination with Washington–or any other actor– it owes the public a full accounting. If it hasn’t, then the question becomes more urgent: why is it agreeing to host a humanitarian corridor that may serve as a staging ground for other people's wars?

What began as a response to a humanitarian crisis now risks morphing into something else entirely. It seems like Bangladesh is not just building a corridor, it is walking a tightrope.

According to a recent United Nations report, Arakan stands at the brink of famine. The warning is dire: not only Rohingyas but ethnic Rakhines themselves may soon seek refuge across the border into Bangladesh.

It is on the basis of this prediction that the UN has urged Dhaka to open a humanitarian corridor. And, astonishingly, the Bangladeshi government appears to be entertaining the proposal– again– with little public scrutiny or strategic clarity.

But famine alone does not explain what’s unfolding. In the past six months, even after the Arakan Army's de facto control over most of Rakhine, nearly 200,000 Rohingya have entered Bangladesh. That’s a direct consequence of targeted hostility on the other side of the border.

Reports point to the Arakan Army not merely ignoring but actively persecuting Rohingya communities. There are even allegations of Arakan Army fighters crossing into Bangladeshi territory–some caught on video "celebrating" inside the border, in plain defiance of Dhaka’s sovereignty.

Meanwhile, the UN continues to press Bangladesh– including sending letters about building shelters for displaced Rohingya– as if the country had the resources, infrastructure, or internal political consensus to absorb another mass influx.

But where is the international accountability for the violence driving this displacement in the first place?

The central question, then, is this: does Bangladesh have any concrete plan for managing this unfolding crisis? Or is the government merely reacting to UN communiqués, improvising national security policy on the basis of letters and famine forecasts?

The ground realities do not inspire confidence as well. Rohingya infiltration continues. Arakan Army activity on or near Bangladeshi soil remains a real threat.

And the “so-called” humanitarian corridor may serve less as a channel for aid than a geopolitical loophole–one that solidifies the Arakan Army’s holdover Rakhine and turns Bangladesh’s southeastern border into a strategic pawn in a broader regional game.

Even the intended beneficiaries of the corridor–the civilians–may not see much relief. There is no guarantee that aid funneled through this corridor will actually reach the Rohingya or vulnerable Rakhine populations.

Without neutral oversight and security guarantees, the corridor risks becoming an empty gesture–or worse, a legitimization of the very actors displacing civilians.

This is obviously not just a simple humanitarian issue; it is a national security concern. The government appears to have acknowledged this–at least symbolically– by appointing Khalilur Rahman, its envoy for Rohingya affairs, as a "Security Advisor" last April.

Yet even this appointment stirred controversy. Rahman’s U.S. citizenship has drawn criticism and raised questions about his strategic alignment at a time when Bangladesh’s sovereignty is seemingly under stress.

More troubling still is the lack of political consensus on this issue. According to multiple media reports, including Samakal, the corridor decision has not been subjected to broad parliamentary debate or cross-party consultation.

Even within the administration, disagreements

reportedly persist. Yet, on April 28, the government officially committed to

the corridor at the UN’s request.

Ambiguity led to public confusion

The perception, now widespread, is that Dr Yunus’s interim government is rushing into this deal –quietly, unilaterally, and dangerously.

But it needs to be understood that a humanitarian corridor without a security plan is not a policy– it’s a liability. And in this case, it’s one that Bangladesh may come to regret.

Recent history offers a sobering lesson: so-called humanitarian corridors rarely remain purely humanitarian for long. From Syria to Sudan, such pathways have often mutated into militarized zones, manipulated by armed actors and foreign powers alike.

The result? Destabilization, protracted conflict, and internal law-and-order breakdowns. Bangladesh would be naïve to assume that its case will be any different.

Security analysts are already sounding the alarm. The trajectory of this proposed corridor–vague in concept and opaque in implementation– raises serious concerns. The architecture of its management remains entirely undefined.

Which agencies within the United Nations will coordinate aid? More crucially, who will control security on the ground? If neutral oversight is not guaranteed, the corridor risks becoming a conduit not for relief, but for chaos.

Equally unsettling is the potential domestic fallout. At a moment when Bangladesh is attempting to navigate a delicate democratic transition, the specter of a foreign-controlled corridor–possibly accompanied by foreign troops or intelligence assets–casts a long shadow over internal politics.

Political actors across the spectrum are uneasy, and rightly so. Any initiative of this scale, undertaken without broad consensus, threatens to further fracture an already polarized political landscape.

The fundamental question still looms: will this corridor actually help resolve the Rohingya crisis? Or will it simply cement a new status quo–one in which Bangladesh is permanently burdened with a displaced population, while the world applauds its "humanitarian cooperation" from afar?

There is little evidence that the corridor will lead to any meaningful reduction in the number of Rohingyas currently sheltering in Bangladesh. On the contrary, if the Arakan Army continues its campaign of displacement and persecution, and if the corridor fails to ensure genuine safety and resettlement within Myanmar, the influx may only intensify.

Bangladesh cannot afford another miscalculation. This corridor may be built in the name of humanitarianism, but unless its objectives, oversight, and outcomes are clearly defined, it risks becoming a Trojan Horse — one that threatens the country’s security, sovereignty, and political stability.

—

Tuhin Khan is a writer, and thinker