True democracies don’t owe mass murderers a ballot line

In any functioning democracy, the political arena must draw a clear line: participation is a privilege, not an entitlement– especially for those with blood on their hands.

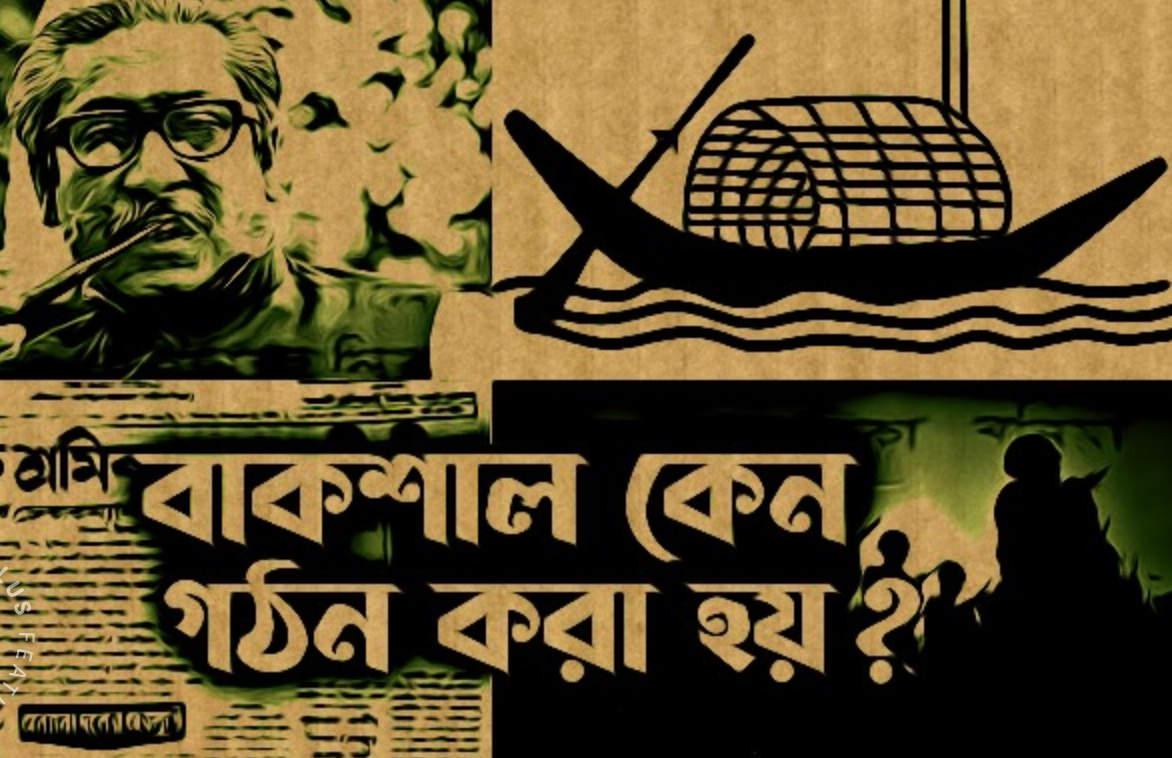

In Bangladesh, that line has been blurred to the point of invisibility. Two major parties–the Awami League and Jamaat-e-Islami–carry the weight of documented mass atrocities. And yet, both continue to operate freely under the protections of democratic legitimacy.

This must end.

Until transparent, independent investigations are conducted into each party’s role in past mass killings– including those committed during their respective times in power –their political registrations must be suspended.

Not disbanded outright, not exiled forever, but withheld pending the outcomes of legal scrutiny. If any party’s name, symbol, or ideological machinery is found to have been directly used in the machinery of mass violence, then those identifiers should be permanently banned from political use.

This isn’t censorship. It’s accountability.

Bangladesh’s political future must include progressive and Islamist voices– but not at the expense of memory or justice. Allowing the slogans, logos, and structures implicated in mass murder to return to mainstream politics is not democratic pluralism.

It is historical revisionism, whitewashing, and in the worst cases, a green light for repeat offenses.

Predictably, critics of this position retreat into the “practical”-- arguing that bans don’t work, that underground politics will flourish, or that it only fuels political martyrdom.

These are arguments of convenience, not principle. What matters isn't whether banning is always effective; it's whether it is necessary in cases where crimes are too large to ignore.

Practical concerns must be addressed–yes–but they do not negate moral imperatives. Democracy is not supposed to be so flexible that it wraps itself around fascism for the sake of procedural comfort.

Think of it like this: if seventy people fall violently ill and ten die after eating bread from a bakery, the first step isn’t to study the economics of bakery closures. You shut the place down, investigate, and take action.

You don’t let the ovens keep running while inspectors trip over flour bags.

The same goes for political entities under investigation for serious crimes–especially when those entities still control portions of the state apparatus.

Stop giving political entities a free pass

The same logic applies in government service: a civil servant facing credible allegations of misconduct is suspended while a case proceeds.

They may still exert informal influence, but it’s nothing compared to the control they wield while officially in office. It’s a basic safeguard for fair process. Why should political parties be exempt?

Bangladesh must move beyond the delusion that democracy can survive without accountability. It cannot. And any attempt to fold known perpetrators back into the system without trial– without even temporary suspension– is not an act of tolerance. It is cowardice.

Suspend them. Investigate them. Let justice speak first. Only then should politics resume.

This is where I find most public discourse faltering–particularly among those who have never dealt with the mechanics of justice or investigations. The concept of “temporary suspension” is grossly misunderstood.

Many assume that when a police officer is suspended for alleged wrongdoing, the matter is closed–that suspension is synonymous with acquittal. Others hear the word “temporary” and conclude that nothing meaningful is being done.

Both views betray a fundamental misreading of what a functioning judicial process looks like.

The scale of atrocities committed by the Awami League– especially during the July–August period and throughout its 16-year grip on power– cannot be investigated without first halting its ability to operate as a political entity.

And I say this not just as a citizen, but as someone who no longer considers the Awami League a political party in the classical sense. What we’re dealing with is not a party but the most optimized management system for Bangladesh’s postcolonial extraction economy.

It is not merely in the system– it is the system.

The deep-rooted Awami problem

To say that “Awami League people” occupy key posts in the army, police, and bureaucracy is a misdiagnosis. The institutions themselves have been retooled into Awami League machinery.

Insert anyone from the opposition–BNP, Jamaat, whoever–and they’d still need Awami League’s geopolitical leverage, particularly its alignment with Indian interests, to replicate even a fraction of its control.

And they wouldn’t succeed.

The deep state in Bangladesh doesn’t just shield the Awami League– it is hardwired to preserve the conditions that make the Awami League irreplaceable.

In such a situation, allowing the Awami League to contest elections under the pretense of liberal democratic continuity is more than naïve.

It’s dangerous. It sets the stage for further conflict, for riots dressed up as rivalries, and for instability that– ironically– will only make the League's authoritarian stability appear preferable in hindsight.

The regime knows this and plays the long game accordingly.

The first and most basic condition for truth-seeking, then, is this: keep them out of elections. Temporarily suspend their right to organize under a party banner. Investigate. Prosecute.

Only after that– and only if cleared–should participation be restored.

But here we collide with a national condition: a deep, generational mistrust of proceduralism. We’ve seen justice used as a tool of spectacle and repression so often that even the word “procedure” feels like a scam.

So when suspension is proposed as a neutral tool to enable investigation, it’s instinctively dismissed as a trick– a hollow performance masking deeper inaction.

And perhaps sometimes it is. But abandoning procedure because it’s been corrupted is no solution.

It’s like Rahim the beedi smoker quitting the newspaper because it ran an editorial urging him to quit smoking. The issue is not the existence of procedure–it’s whether that procedure still serves justice.

That’s what we must fight for: not an end to process, but a process worth trusting again.

And that begins with one clear act: suspend the Awami League. Stop the system. Then see what the truth reveals.

—-

Mikail Hossain is a researcher and analyst