After five decades and dozens of “questionable” verdicts, Jamaat’s apology is a political demand, not a moral one

In the long, jagged aftermath of Bangladesh’s Liberation War, there are wounds still unhealed–and others that have already been addressed through the rule of law.

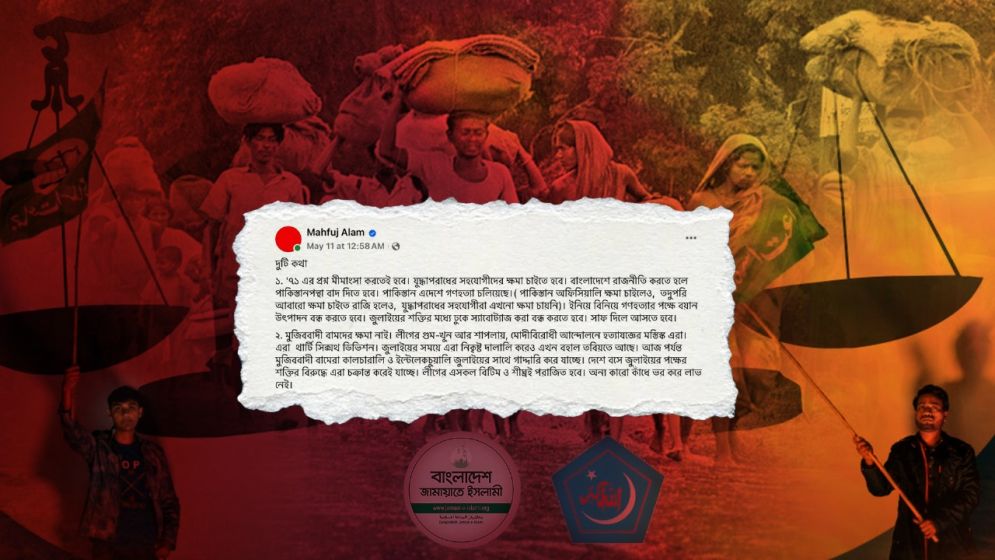

So when public figures like Mahfuj Alam demand fresh apologies from the deemed “collaborators”-- more than five decades after the blood-soaked birth of this nation– one has to ask: are we reopening old scars for justice, or for politics?

Let us recall the historical record, not as myth or memory, but as documented fact.

In 1972, the newly-formed Bangladesh government enacted the Collaborators Order, creating a legal path for holding accountable those who sided with the Pakistani military junta. Roughly 50,000 collaborators were arrested.

Over 37,000 cases were filed. Convictions? Just 752. The process was far from perfect, but it was real, it was judicial, and–crucially– it happened.

Then came the general amnesty of 1973, pardoning over 36,000 alleged collaborators–but sparing no one with blood on their hands. Murderers, rapists, arsonists: no forgiveness was offered.

That chapter, for better or worse, was closed.

What remained unresolved was the separate, far more chilling dossier: the prosecution of high-level war criminals– many of whom hid in plain sight for decades, often under the political canopy of Jamaat-e-Islami.

It wasn’t until the Awami League returned to power in 2009 that real momentum gathered around the long-awaited International Crimes Tribunal (ICT). Since then, 52 individuals have been sentenced to death for crimes against humanity.

Most were leaders of Jamaat. And most of those sentences– however controversial in international circles– have been carried out.

Justice, however delayed, was done.

But here’s the political crux: once these trials were complete, once the hangings were done, the tempo faded. Three tribunals became one. Media coverage dwindled.

The final years of the AL government treated the ICT like a side show– symbolic, but sidelined. It was, in every practical sense, mission accomplished.

So if Jamaat today argues that it has paid its dues– in blood, in legacy, in legal accountability– it is not entirely without basis.

What more is being demanded? An apology? For crimes its senior leaders were already tried and executed for? In political terms, is this about remorse– or retribution?

Calls for apology must be rooted in moral clarity, not political convenience. If the demand is for reconciliation, it must be mutual, not selective.

If it is for history, it must be consistent–not revived only when it suits a moment.

Is Jamaat’s argument or

stance flawed?

Bangladesh deserves to reckon with its past, but it must also be honest about what has already been reckoned with. Otherwise, we risk weaponizing memory in the service of partisanship– and confusing justice with vengeance.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth– one that many in the political mainstream whisper in private but rarely dare say aloud: the very process by which Jamaat leaders were prosecuted and executed may not stand up to the scrutiny of history. Or the law.

Serious concerns about fairness, transparency, and due process have long dogged the International Crimes Tribunal.

International observers, human rights watchdogs, and even voices within our own judiciary have raised red flags.

The Appellate Division of the Supreme Court has recently been confronted with some of these arguments. They’re not fringe complaints. They go to the heart of the legitimacy of these verdicts.

So Jamaat, if it wishes, has the political leverage to flip the script entirely. It can argue–with a straight face and some legal cover– that its senior leaders were not judged, but hunted.

That their executions were not the conclusion of due process, but the byproduct of political theater. And if that argument sticks, it’s no longer Jamaat that must apologize. It’s the state.

And then what? Do we apologize to the families of those hanged? Do we admit that, in our rush to settle historic scores, we cut corners on justice itself?

If that’s the rhetorical battlefield, then those now demanding an apology from Jamaat must be prepared for a sharp political counteroffensive.

Because if the trials were flawed, then the moral high ground gets muddy very quickly. "Tokhon toh apnarey backfoot e jaite hobe."

Moreover, Mahfuj Alam’s demand– abstract, sweeping, and aimed at an undefined group of “collaborators”-- risks precisely the kind of historical imprecision that fractures societies.

Without clear criteria or evidence, this kind of call doesn’t heal national trauma; it deepens it. It reduces the moral clarity of 1971 into a weapon of convenience, wielded at will against a shifting and faceless enemy.

The liberation war was a just war. Its memory must be protected– not politicized.

But if we insist on dragging the past into the present, let us at least do it with precision, legal integrity, and intellectual honesty. Anything less, and we don’t honor 1971. We distort it.

—-

Chowdhury Tanzim Karim is a Barrister and Advocate of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh