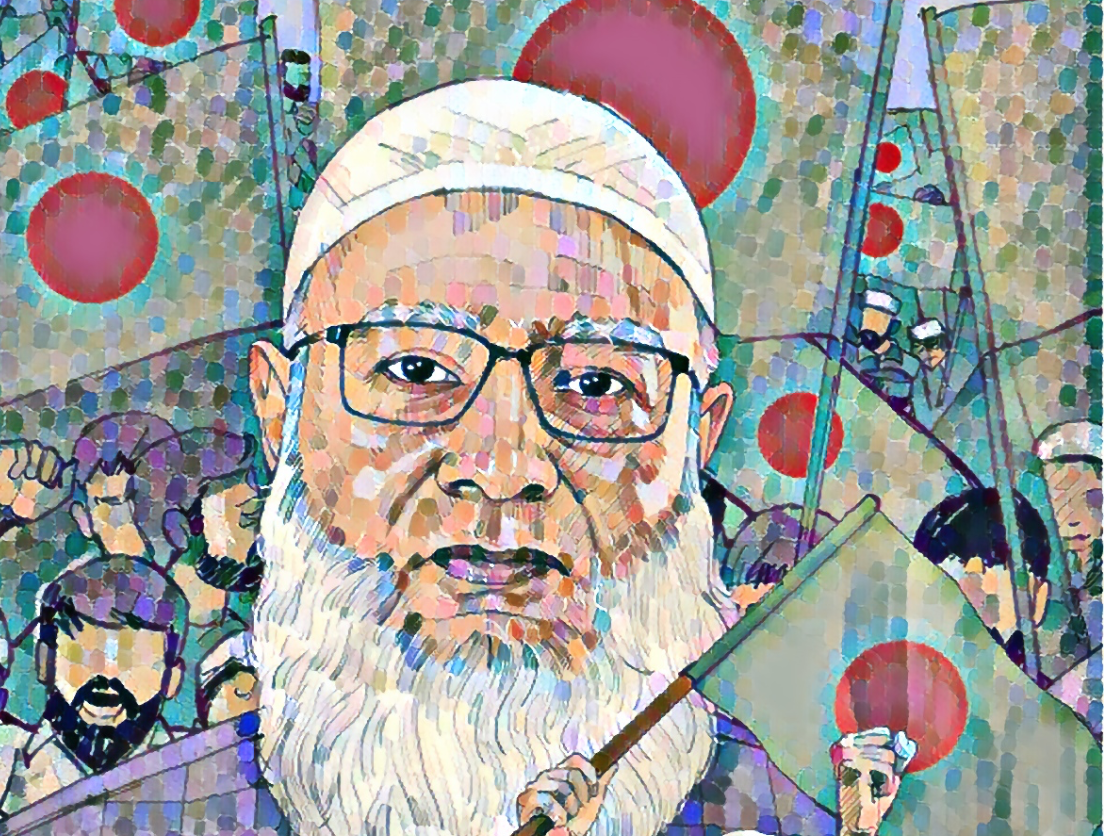

From apolitical to aligned: Why Jamaat-e-Islami will get my vote in the next election…

As the political landscape grows increasingly turbulent—torn between calls for electoral reform and the urgency of a long-overdue national vote—the prospect of a genuinely free and fair election remains elusive.

For the past 15 years, Bangladesh has been denied that fundamental democratic exercise. The rhetoric of democracy persists, but the reality on the ground tells a different story.

And yet, as an ordinary citizen with no political affiliation but committed to the democratic process, I am prepared to wait—for the ballot, for the moment, for the chance to cast a vote that truly counts.

When that moment comes, my vote will go to Jamaat-e-Islami. You may ask why.

The answer is not impulsive; it is the result of long observation, critical reflection, and a list of reasons I’ve weighed carefully.

Jamaat’s early history is, undeniably, a burden it continues to bear. Its opposition to the creation of Bangladesh during the 1971 Liberation War remains the original sin in the eyes of many—a stain that time has not washed away, even after 57 years.

The party’s failure to support the movement for independence, coupled with the atrocities committed by the Pakistani military, left it politically isolated in a new nation built upon the ideals of liberation and justice.

This historic stance has since shaped Jamaat’s political fortunes, or misfortunes. Essentially never able to contest elections alone, sans the ‘91 election, the party has been relegated to the role of junior partner, a tool for larger parties in pursuit of electoral gains.

When aligned with the BNP, Jamaat was vilified by the Awami League; when it tilted toward the League, the BNP repaid the gesture in kind. In every coalition, Jamaat became both asset and scapegoat—praised in whispers, denounced in public.

Yet amid this stigmatization, Jamaat has not vanished. In fact, it has quietly endured. Its grassroots networks remain robust, its ideological clarity—however controversial—unshaken.

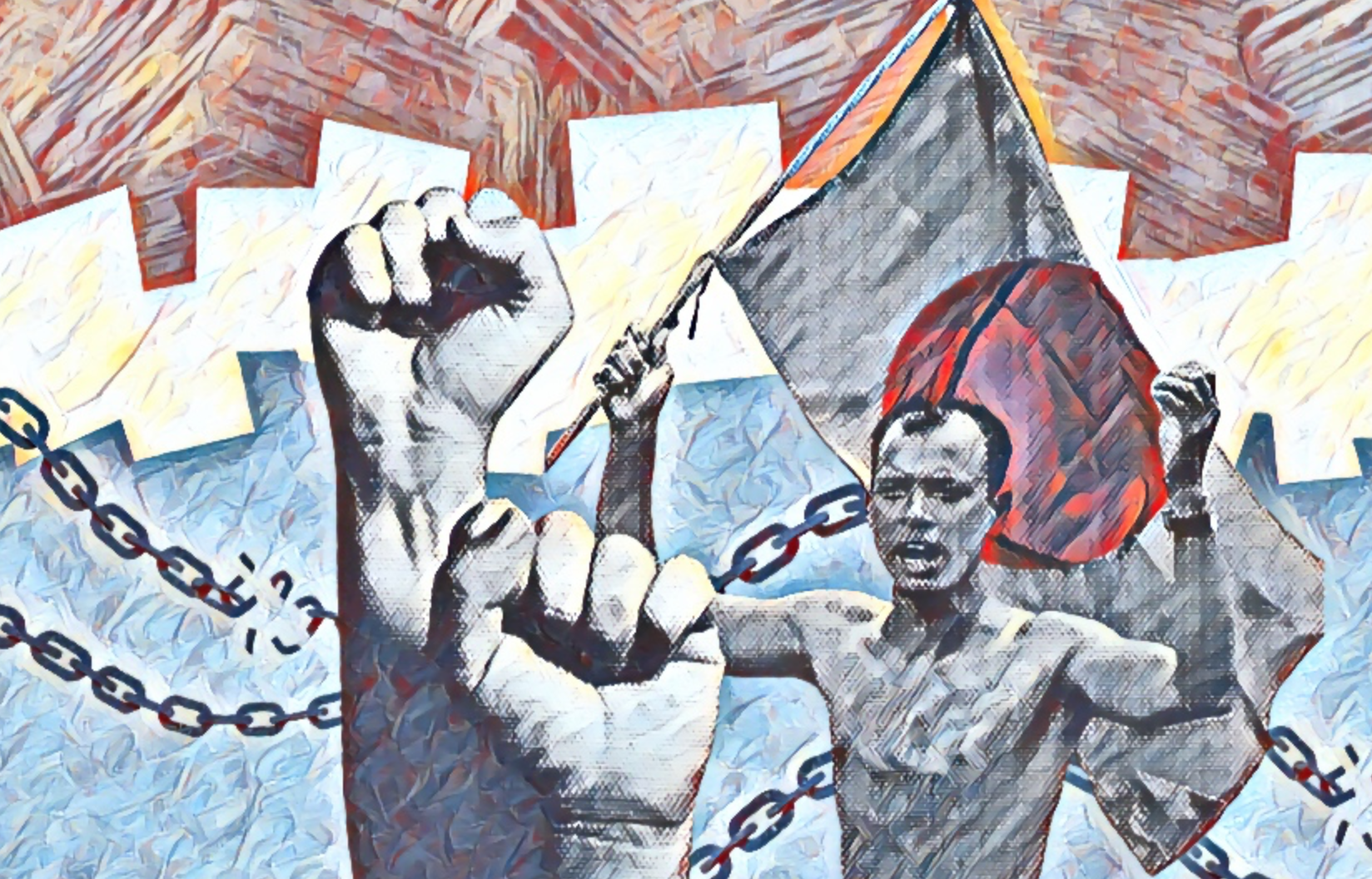

Its student wing, Islami Chhatra Shibir, has consistently shown a capacity for mobilization that rivals larger, more mainstream student organizations. During the mass movement of 2024, their role was anything but marginal.

They were present in the streets, on campuses, and behind strategies that accelerated the July uprising. Some paid with their lives. Many others became symbols of a new kind of resistance.

To its followers, Jamaat is a disciplined, resilient force that has survived decades of marginalization, military crackdowns, and what they view as politically motivated war crimes trials.

The party argues that its leaders were not given justice, but vengeance, through what they term "kangaroo courts" under prolonged Awami League rule.

Of course, none of this erases history. Nor does it absolve the party of its role—or absence of one—during the country's defining moment.

But in a political arena where democratic values are too often compromised by expediency, and where opposition parties have been systematically weakened, Jamaat’s survival and re-emergence present an uncomfortable question: Can a party, once shunned for its past, re-legitimize itself through persistent civic action and organizational integrity?

Jamaat’s case in point

This is not to endorse Jamaat, nor to dismiss the pain of history. But in 2024, for some citizens disillusioned with both major parties and yearning for an alternative, Jamaat’s consistency—even in adversity—is its own form of appeal.

Whether this translates into sustainable political legitimacy remains to be seen. But dismissing that appeal outright may be yet another miscalculation in a country long accustomed to them.

At the heart of Jamaat’s endurance lies a trait often overlooked in Bangladesh’s turbulent political arena: organizational discipline.

Among the cacophony of splintered leadership, factional infighting, and shifting allegiances that plague the country’s mainstream political parties, Jamaat—and its student wing, Islami Chhatra Shibir—stands apart.

Internal strife, which has become almost a defining feature of larger parties, is virtually nonexistent within Jamaat-Shibir. Its leadership structure is both hierarchical and remarkably stable.

Orders flow from the top down, not as authoritarian diktats but as part of a deeply embedded culture of obedience and shared ideology. Dissent, when it occurs, is resolved internally without public spectacle.

In a country where party meetings often devolve into shouting matches—or worse—this discipline is, in the eyes of its supporters or neutral onlookers, not rigidity but strength.

Even more defining than its structure, however, is the moral foundation upon which Jamaat rests. Its members are steeped in religious education not only as a matter of personal belief, but as a formal part of political life.

Daily prayers, study of Islamic texts, and routine moral training are expected, not optional. For Jamaat members, integrity is not merely a campaign slogan—it is a spiritual obligation. Theft, extortion, or corruption are considered violations not only of the law, but of divine accountability.

This has had a tangible impact. Despite holding parliamentary seats and participating in successive governments, Jamaat has remained relatively untainted by corruption scandals.

Even their harshest political adversaries have struggled to accuse them of financial impropriety—a rare feat in a political culture often defined by patronage, backdoor deals, and abuse of office.

Where lies Jamaat’s strength

This contrast has become increasingly apparent in the wake of the 2024 mass uprising. For many, the events of that year were a turning point—a rare convergence of youth-led activism, political courage, and grassroots mobilization.

Jamaat-Shibir played a decisive role. And perhaps more significantly, they did so with a level of strategic sophistication that surprised even long-time observers.

Following the July movement, Shibir quickly pivoted from protest to program. They organized seminars, public forums, academic festivals, and even inter-party dialogues—offering rare platforms for ideological exchange in a country where debate is too often replaced by dogma.

In an unprecedented move, they invited student groups from opposing ideologies to participate in public criticism of their own policies and positions.

In a political culture where engagement with "the enemy" is often seen as betrayal, this openness was a radical gesture.

These actions did not go unnoticed. For many students, educators, and even apolitical observers, the post-July months showed a version of Jamaat-Shibir that the nation had rarely seen—a political organization willing to listen, to host, to reform.

The optics were different. The messaging was different. And most importantly, the methods were different.

Of course, skeptics remain. The legacy of 1971 still looms large. But for a growing number of young people disillusioned by corruption, authoritarianism, and the erosion of democratic norms, Jamaat’s disciplined, values-based approach is beginning to resonate.

They see not the party of the past, but a political force recalibrated for the future.

The question now is not whether Jamaat can shed its past—that may never fully be possible—but whether the country is willing to engage with the version of Jamaat that exists today.

In a country where over 90 percent of the population identifies as Muslim, it is unsurprising that political aspirations often reflect the values and cultural expectations of that majority.

Jamaat-e-Islami has long positioned itself within this reality, advocating for a political system informed by Islamic ethics while also emphasizing its commitment to pluralism and coexistence.

Contrary to the portrayal often pushed by rival parties, Jamaat’s stance toward religious minorities is not one of exclusion but of inclusion—grounded, they argue, in Islamic principles of tolerance and mutual respect.

Still, persistent fears linger. One of the more enduring taboos surrounding Jamaat—frequently weaponized by political opponents—is the idea that a Jamaat-led government would impose religious mandates: compulsory prayer, mandatory veiling for women, or the enforcement of rigid religious codes.

Yet, the party’s leadership, including its Ameer Dr Shafiqur Rahman, has publicly rejected these notions. They have stated unequivocally that personal religious practices will not be coerced and that faith, in their view, cannot be sustained through force.

These declarations have yet to fully counter the deep-rooted skepticism, but they signal an effort to dispel the myths that have long haunted the party’s public image.

Forward looking views

This effort to reposition itself comes at a moment of deep frustration with Bangladesh’s political status quo. Since independence in 1971, successive governments—military and civilian—have presided over waves of corruption, dysfunction, and declining public trust.

The state’s institutions, from the judiciary to the bureaucracy, have become increasingly politicized. The rule of law has eroded.

And the country’s international reputation, once buoyed by its resilience and economic potential, has suffered under the weight of graft, cronyism, and institutional decay.

It is in this context that Jamaat’s emphasis on honesty, discipline, and ideological consistency resonates with a growing segment of the population.

While mainstream parties have been marred by scandal after scandal, Jamaat’s track record of relative financial transparency and lack of corruption charges stands in stark contrast.

Their organizational coherence, moral positioning, and grassroots connections are increasingly seen not as relics of the past, but as rare political assets in a climate defined by chaos and mistrust.

Yet even as Jamaat’s strengths become more visible, the path forward remains fraught. To truly establish itself as a viable alternative, the party must shed its historical overreliance on alliances with larger political players and foreign patrons.

It must walk alone—on principle and with people’s trust—if it wishes to reintroduce itself not as a proxy, but as a genuine force for reform.

And to do that, it must also confront the taboos that still cling to its name, not with defensiveness, but with dialogue, transparency, and action.

The months following the 2024 uprising have provided Jamaat with an opportunity—a rare window to reimagine its place in national politics.

Whether it can seize that moment will depend not on its history, but on its ability to forge a future grounded in self-reliance, ethical governance, and a willingness to engage openly with those who remain skeptical.

The party’s core question is no longer whether it can survive, but whether it can lead. That answer will not be found in slogans or sermons—but in the choices Jamaat makes in the months and years ahead.

—-

Hasan Habib is an engineer turned entrepreneur of safe, organic foods. He is the owner of Sunnah Delight food brand