ATM Azhar’s release was ‘justified’ but it exposes the cracks in Bangladesh’s War Crimes Tribunal

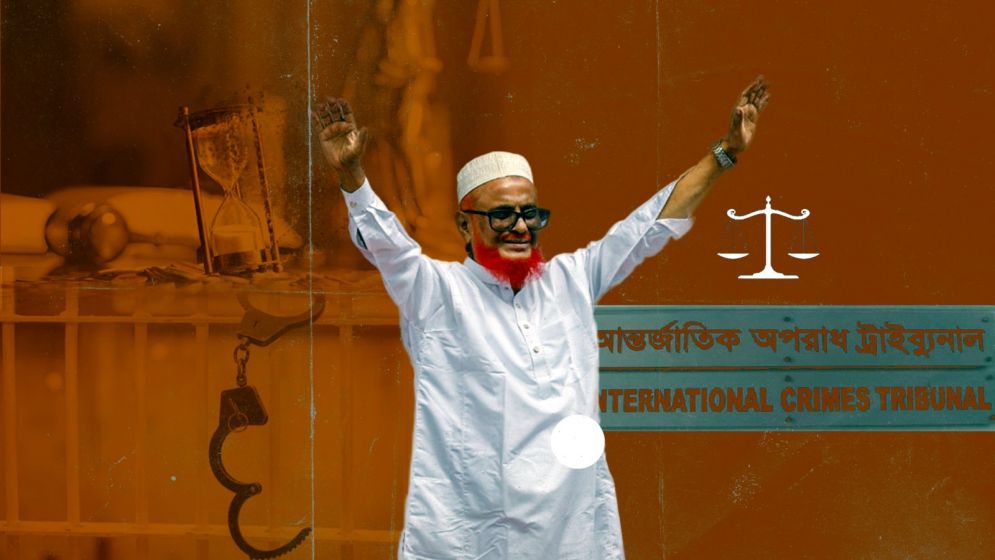

The recent decision to release ATM Azharul Islam–a man convicted of crimes against humanity–deserves far more scrutiny than it has received.

A closer examination of the court’s reasoning reveals a troubling truth: this release wasn’t granted on questions of guilt or innocence, but on flawed procedural grounds. The judiciary, at least in this ruling, appears to have sidestepped the moral weight of justice in favor of legal technicalities.

We may learn more once the full verdict is published. But the signal is clear: something is seriously amiss.

The blame lies not just with the judiciary but with the Awami League government, which long ago allowed political expediency to poison the war crimes trials. By turning these proceedings into a partisan battlefield, they undermined both the credibility of the trials and the larger pursuit of justice.

When I wrote about this issue a year or two ago–about the verdict in the Delwar Hossain Sayeedi case–the cracks in the system were already visible.

There was, however, a window for course correction after July. A genuine opportunity emerged to rescue the tribunal process from its political entanglements. For a brief moment, the hope of a more impartial, legally sound mechanism for addressing wartime atrocities seemed within reach.

Then came the restructuring of the prosecution team–and with it, the return of controversy.

As Prothom Alo reported on April 8, at least four members of the newly appointed prosecution, including the current Chief Prosecutor, had previously represented the accused in war crimes cases. That’s not just a bad look–it’s a legal and ethical quagmire.

The government’s response? Evasive at best. Chief Prosecutor Tajul Islam insists there is no direct conflict of interest in the ATM Azhar case. But that argument deliberately misses the point.

What we are seeing is not direct but indirect conflict–deeply embedded in the institutional structure of the tribunal itself.

Consider this: the same tribunal, the same historical context, and often the same cases are now being prosecuted by individuals who once defended the very people they’re tasked with convicting.

When the chief architect of a prosecution once built defenses for the accused, impartiality becomes not just suspect–it becomes implausible.

And it doesn’t stop with one case. Tajul Islam isn’t just a participant; he is the lead prosecutor, the voice of the state in all war crimes-related cases. His dual roles–past and present–cast a long shadow over every judgment the tribunal delivers.

The dilemma of a restructured ICT

The net result is threefold: First, it erodes public trust. Second, it empowers revisionist narratives that deny or downplay the brutality of 1971. And third, it risks turning what should be an unimpeachable moral reckoning into just another political farce.

This is no longer just a question of whether ATM Azhar deserves release. The deeper, more alarming question is: Can the war crimes tribunal still be trusted to deliver justice–or has it become just another casualty of political manipulation?

Azhar’s lawyer, Shishir Monir, proposed forming a “review committee” to re-examine past verdicts. On the surface, this sounds procedural, even responsible. But if such a committee is convened while Tajul Islam remains Chief Prosecutor, the conflict of interest becomes not just theoretical, but direct–and legally untenable.

Tajul Islam served as the defense lawyer in at least two of the tribunal’s most consequential cases: those of Abdul Quader Mollah and Ali Ahsan Mohammad Mojaheed, both executed for their roles in the genocide.

To now play the role of prosecutor, while also potentially overseeing a review of the very verdicts he once fought against, is an ethical and legal absurdity. It shatters the wall meant to separate advocacy from adjudication.

The state prosecutor who represented the government in ATM Azhar’s hearing, HM Tamim, once served as legal counsel for another war crimes accused in the same tribunal.

This is not merely about “conflict of interest” in the abstract. The situation violates core principles of professional ethics, enshrined in both the Bangladesh Bar Council Canons and United Nations legal guidelines.

These rules are clear: lawyers must recuse themselves from cases where prior involvement could compromise their impartiality. Yet here, such conflicts are not just present–they are defining the structure of the tribunal.

Then there’s the appearance of impropriety–the legal concept that justice must not only be done, but must be seen to be done. In law, perception matters. A judge or prosecutor may be technically neutral, but if the public perceives them as compromised, the legitimacy of the process erodes.

The tribunal’s current structure fails this test repeatedly.

Why has it come to this?

There are several reasons, but the most important lies in the entanglement of political interests.

The war crimes of 1971–and increasingly, the violent suppression and killings of 2024–are at the heart of Bangladesh’s partisan divide. The Awami League has used the tribunal as a vehicle for political validation, while its rivals have distanced themselves entirely.

That abdication has allowed procedural flaws and structural weaknesses to fester unchecked.

This political vacuum has created a dangerous paradox. While the trials promised moral closure for a nation traumatized by genocide, they have instead become a source of national division–and now, legal dysfunction.

The failure to maintain prosecutorial independence, to guard against conflicts of interest, and to preserve the integrity of judicial proceedings has undermined the very principle the tribunal was meant to uphold: that there can be no reconciliation without justice.

Bangladesh once stood at the cusp of setting a rare example in post-conflict accountability. Instead, we are watching the machinery of justice fall prey to the same political gamesmanship it was meant to rise above.

If this trajectory continues–if the tribunal becomes the subject of review under the supervision of its former defense attorneys—then the review will not be of the verdicts. It will be of the tribunal itself.

And history will not be kind.

The precedent set by ATM Azharul Islam’s verdict casts a long, dark shadow. By releasing him on the grounds of procedural flaws–rather than reconsidering the substantive crimes–the court has sent a dangerous message: that accountability can be unraveled not through evidence, but through technicality.

And the implications go far beyond one case.

This very same tribunal is currently handling the trial related to the July 2024 killings, an event still raw in the nation's political psyche. Can we trust the tribunal–mired in conflict of interest, prosecutorial contradiction, and legal controversy–to carry out this process in a way that is impartial, apolitical, and internationally credible?

If the answer is no–and that answer is becoming harder to avoid–then what lies ahead? Will Bangladesh descend into yet another generational standoff over the meaning of justice, just as it has with 1971?

Right now, there’s no definitive answer–only an urgent need to confront the question head-on.

What should be done

Here’s what must be done.

First, the International Crimes Tribunal in its current form must be dismantled or radically restructured.

That means removing or amending its most controversial clauses, eliminating all traces of prosecutorial conflict, and rebuilding the institution from the ground up with full transparency and oversight. Anything less will leave the process permanently tainted.

Second, legal justice alone is not enough. Bangladesh needs a truth and reconciliation process–a national mechanism to document, discuss, and confront the traumas of 1971 and 2024. Not to erase guilt, but to elevate truth above political expediency.

Without this, the judicial process will remain a battlefield, not a forum for justice.

Right now, political actors may attempt to distance themselves from the tribunal’s legacy, placing the burden on the transitional Yunus government. But none of them–neither Awami League nor Jamaat, nor the coalition parties in between–can afford to wash their hands of this.

They will all return to power, eventually. And when they do, they will inherit the institutional and moral fallout of these unresolved trials.

If future governments fail to translate the aspirations for accountability–whether for 1971 or 2024–into a truly impartial and lawful framework, they too will join the long list of actors who failed the nation in its pursuit of justice.

Justice that serves only the victors is not justice. Justice that collapses under the weight of political convenience becomes farce. And without a real resolution to these legacy crimes, any hope for a new political culture in Bangladesh–a culture built on consensus rather than vendetta–remains a distant dream.

This is no longer just about correcting the course of one tribunal. It's about whether Bangladesh can find a political and legal language that transcends the wounds of the past.

Or whether it will remain trapped by them.

—-

Tuhin Khan is a writer, and thinker