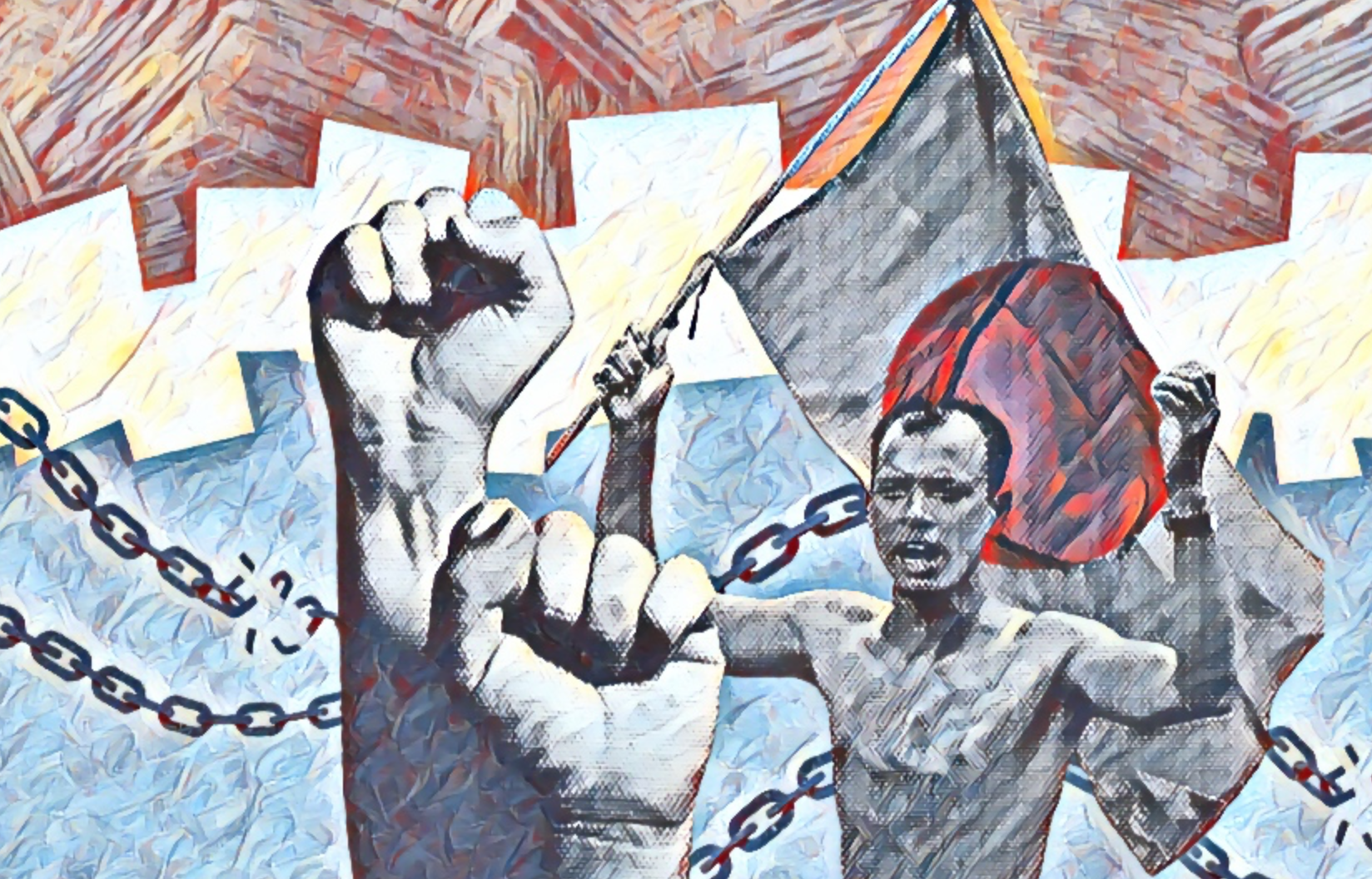

How July uprising proved that homogeneity was Bangladesh’s secret weapon against India’s neo-colonial overreach

For nearly twenty years, Indian intelligence officials believed they had perfected the art of quiet conquest. Bangladesh, they assumed, was under control–through intelligence infiltration.

With the Awami League as a pliant political proxy, New Delhi embedded itself in Dhaka’s judiciary, police, intelligence services, and, most critically, the upper ranks of the military.

It was a strategy straight out of the colonial playbook: subdue a neighbor by subterfuge. A Hindutva-driven vision of regional hegemony, dressed in the language of secular democracy. A slow-motion annexation, carried out with surgical stealth.

And for a time, it worked.

But on August 3, 2024, in the Darbar Hall of Dhaka Cantonment, that illusion collapsed.

In a packed military briefing attended by thousands of officers in person and online, Bangladesh’s Chief of Army Staff General Waker Uz Zaman–despite his own familial ties to former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina–delivered a line that cracked the regime’s spine:

“The Army will no longer open fire on the citizens.”

Seven words. That was all it took to unravel decades of strategic planning.

Within 48 hours, the Hasina regime was gone. Her final reported words before fleeing the country said it all:

“If the police could be brutal to the citizens, why couldn’t the Army?”

She never understood the answer. But it was existential.

India’s planners failed to grasp one thing they couldn’t engineer or override: the cultural homogeneity of Bangladesh. Unlike the subcontinental mosaic of India or Pakistan, Bangladesh is defined by a singular demographic identity. One religion. One ethnicity. One language.

Across villages and cities, an invisible lattice of kinship and communal memory ties its people together.

This unity, long ignored by Delhi’s tacticians, was their blind spot. They believed Bangladesh could be manipulated like a fractured colony–that power could be maintained by stoking internal divisions.

But there were none to weaponize.

And when the moment came, it wasn’t ideology or opposition politics that ended their grip. It was the refusal of a unified people–and a military with enough of a conscience–to pull the trigger.

-683ab8b665c66.png)

A empire built on sands and fog

The architects of Dhaka’s shadow occupation toasted their brilliance for two decades. They never saw the soul of the nation coming.

Empires survive as much with firepower as through division. The British Raj mastered this with chilling precision by fragmenting the subcontinent.

The architecture of their control relied on what they called “martial races” and regimental segregation: Jat soldiers deployed against Bengalis, Gurkhas marched into Punjab, Sikh battalions unleashed on Muslim rebellions in the United Provinces.

These deployments were logistical and psychological. A soldier who shared no language, no faith, no emotional tether to the people he was ordered to suppress would obey without pause. Empathy was a liability. Distance made violence easier.

Independent India and Pakistan inherited the blueprint and kept it running. In Kashmir, the Indian state responded to dissent with armed forces imported from the Hindi heartland– men who viewed the Valley through a lens of cultural alienation.

In Manipur, Assamese troops were sent in to manage Meitei tribal unrest, selected precisely because they wouldn’t flinch.

Pakistan adopted the doctrine just as ruthlessly. In 1971, when East Pakistan demanded dignity and autonomy, the generals in Rawalpindi responded with annihilation. Bengali officers were sidelined, and the task of crushing the rebellion was handed to Punjabi and Pathan regiments– troops who could not understand the language or culture of the people they were sent to dominate.

Their commanders referred to Bengalis as subhuman, and what followed– the massacres at Dhaka University, the rapes in the countryside, the scorched-earth campaigns– were the inevitable result of a system designed to erase identification, and with it, mercy.

That logic still thrives. In Karachi, the state relies on Pashtun Rangers to police a Muhajir-majority population. In Balochistan, Punjabi regiments enforce order over a region that wants nothing to do with Punjabi rule. Keep the enforcers detached, and you keep the guns pointed outward.

But this is exactly where Bangladesh breaks the script.

Here, the imperial algorithm falters. There are no convenient “others” to import. No linguistic gap to exploit. No religious chasm to widen. A Bangladeshi soldier confronting a protestor in Khulna sees not an abstraction, but a reflection– someone who prays in the same mosque, eats the same rice, speaks the same tongue. He doesn’t need a briefing to understand the grievance; he lives it.

There is no buffer of difference to anesthetize the conscience.

Misunderstanding the lack of ethnic divide

This is what Indian and Pakistani strategists–and their colonial predecessors–fundamentally misunderstood. The divide-and-rule model fails in a land not divided. Bangladesh’s strength isn’t performative nationalism or manufactured unity.

It’s something far more potent: a deep, lived homogeneity that makes state-sponsored violence against its own citizens not just morally fraught, but operationally unsustainable.

That is why, on August 3, when the Chief of Army Staff stood before the officer corps and refused to authorize gunfire on civilians, the decades-old machinery of coercive control collapsed in a single sentence.

Because in Bangladesh, the soldier knows the face in the crowd.

In July 2024, the Bangladesh Army was ordered to suppress an uprising. But what it encountered was not a mob. It was its own reflection.

The children flooding the streets were not just some faceless agitators–they were sons and daughters of soldiers. Classmates of junior officers. Neighbors. In some cases, family.

Martyr Mughdo, whose killing electrified the protests, was the neighbor of a female army officer–one who reportedly broke down in tears during the fateful Darbar Hall meeting. A police officer’s own son was riddled with bullets. Helicopter gunners fired on rooftops, not knowing–or perhaps knowing too well–that the children below could have easily been their own.

Deployment, in effect, became a suicide of the soul. Pointing a gun at protestors was like pointing it at a mirror. The man in the crosshairs was familiar–in face, in faith, in blood.

The Awami League's mistake was also civilizational. It failed to understand that in Bangladesh, the Army is not an occupying force drawn from afar. It is woven into the same social fabric as the people it was asked to brutalize.

Soldiers and civilians live in the same neighborhoods, attend the same weddings, pray in the same mosques. Even military families found themselves harassed under the government’s paranoia: surveilled, searched, intimidated by the very regime they were meant to protect.

By July, something irreversible had happened. The Army didn’t break its oath. It simply refused to betray its people.

Years of careful grooming by the Awami League–promotions, patronage, ideological filters–came undone in an instant. The guns didn’t jam. The fingers simply wouldn’t squeeze the trigger.

The architecture of control that had held for decades– built on division, foreign backing, and a mythology of permanent rule– collapsed like a paper wall soaked in truth.

The uprising was personal. Familial. Intimate. A revolutionary scale mass movement not just against power, but against the lie that power could ever outrun memory.

—

Arif Hafiz is a political analyst, cultural critic, and independent columnist.