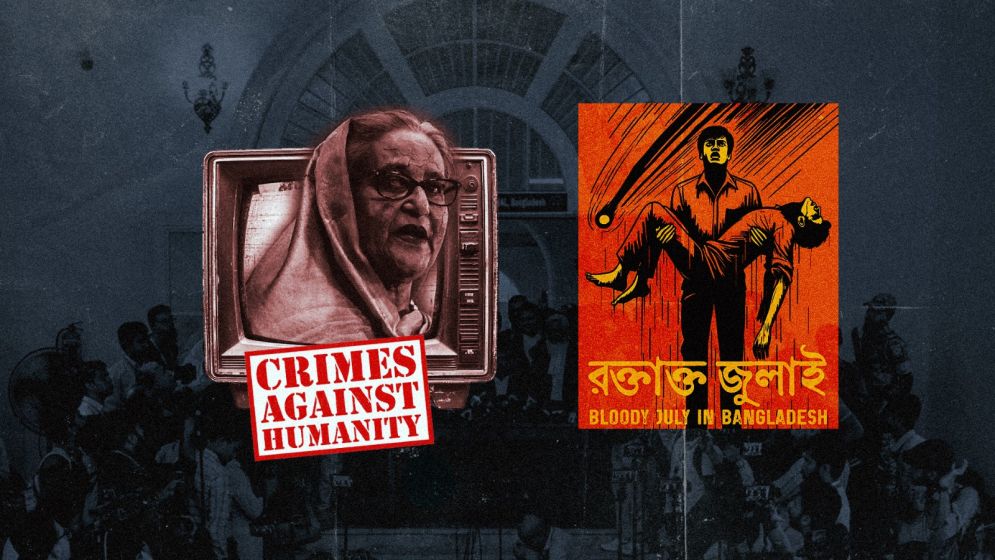

What televising Hasina’s trial means for Bangladesh’s democracy and justice system

For the first time in Bangladesh’s history, a former prime minister is standing trial for crimes against humanity and the entire nation is watching.

Sheikh Hasina, the longtime leader of the banned Awami League party is now the defendant at the International Crimes Tribunal in Dhaka. The proceedings are being broadcast live on state television.

What unfolds in that courtroom may be more than a legal reckoning–it could mark a turning point in how Bangladesh confronts power, truth, and memory.

Globally, the public airing of such trials has often signaled a nation’s deeper struggle with its own identity. The Nuremberg trials–though not televised–set a precedent for postwar justice, establishing the moral authority of international law.

Israel’s televised prosecution of Adolf Eichmann in 1961 forced a young country to come to terms with the Holocaust in real time. South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission made accountability a national spectacle, with victims and perpetrators sharing the stage, however painfully. Rwanda’s Gacaca courts turned villages into courtrooms, making truth-telling a communal act.

Bangladesh has long been a country where power often shields itself behind myth, memory, and muscle. For years, Sheikh Hasina portrayed her party as the sole custodian of the Liberation War's ideals.

But beneath the surface, critics say her rule became synonymous with authoritarian drift–enforced disappearances, systemic corruption, and the silencing of dissent. That such a figure is now in the dock is seismic.

For victims, this is the first glimpse of official acknowledgment. For the country’s military, intelligence, and bureaucratic elite–long perceived as untouchable–the trial brings long-whispered names into daylight.

For Bangladesh’s youth, many of whom have inherited narratives steeped in partisanship and myth, it is a rare chance to witness political accountability unfold in real time.

The interim government led by Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus appears intent on setting a new precedent: justice as public record. Whether this moment leads to genuine reform or devolves into partisan theater remains to be seen.

But one thing is already clear: history is being written–and televised.

The expected meltdown

What makes this moment unprecedented isn’t just who’s on trial–it’s who’s watching, and who’s no longer listening.

Predictably, the Awami League’s echo chambers–along with their well-worn amplifiers in New Delhi–are sounding the alarm. A coordinated media push has already begun, branding the trial a “witch hunt,” a “vendetta,” a “threat to regional stability.”

Indian think tanks have stepped in, warning of a “rise in militancy” while conveniently ignoring the extent to which their government sustained the very regime now under legal scrutiny.

It’s a familiar script. Crisis management through deflection. But this time, the audience has changed.

From Dhaka’s university campuses to the village tea stalls in Rangpur, a new chorus is emerging: “We want justice, not just elections.” It’s a slogan, but also a reckoning. The people are no longer content with the shallow rituals of democracy. They want accountability–real, televised, and inescapable.

The opposition, for its part, senses the shifting tides. BNP leaders have called for national elections before any tribunal proceedings–an unsurprising move. Yet they’ve also pledged to pursue accountability themselves if returned to power.

Still, reports from rural districts hint at a more complex reality: BNP operatives quietly sheltering local Awami League ward leaders. If BNP forms the next government, will it protect the tribunal–or barter it away in exchange for favors from India, the Army, or former rivals?

A recent UN human rights report warned precisely of this: that public trials risk being hollowed out by backroom bargains. This is where the decision to televise the proceedings carries lasting weight.

Broadcasting the trial ensures that justice is not only done–but seen to be done. It builds public confidence in a country where trust in institutions has long been eroded. It also signals a shift in political culture: from impunity to transparency, from authoritarian legacy to civic reckoning.

For a generation raised on curated history and censored media, it’s a rare form of national education.

And

for the political elite–on all sides–it is a warning: betrayal of public trust

will not remain buried. Visibility makes complicity harder to hide. It sharpens

the public’s ability to recognize the early signs of authoritarian

drift–partisan bureaucracy, criminalized opposition, press repression–and

builds resilience for the future.

A bold step by the interim government

This visibility, too, offers a quiet vindication for the interim government under Muhammad Yunus. Often criticized for caution or inertia, it now has something concrete to point to: progress unfolding live, a nation watching its history shift in real time.

There’s irony in all of this, of course. The very tribunal now holding Sheikh Hasina to account was one she herself established. It was under her leadership that the International Crimes Tribunal was revived–to try war criminals, but critics argued it was used to eliminate political opposition.

Now, that same institution may decide her own fate. If she once found it legitimate enough to execute her rivals, she can hardly discredit it now that the scales have turned. That said, the risks remain real.

Justice, in politically charged contexts, is always a high-wire act. Witnesses may be intimidated–subtly or otherwise–by those with much to lose. Foreign actors, especially in the Indian media ecosystem and intelligence-linked outlets, are already attempting to frame the process as destabilizing.

The ghost of the Shahbagh movement looms large. Once hailed as a grassroots call for justice, it is now widely seen as orchestrated by the very regime it defended. Should emotions again boil over, the spectacle could boomerang: Hasina loyalists, this time, on the receiving end of public fury.

And there is the darker possibility that Awami League hardliners may not go quietly. Should damning revelations surface, some may seek to disrupt proceedings, provoke unrest, or manufacture chaos to undermine the tribunal’s legitimacy–or even incite an overreaction that could serve their narrative of persecution.

Yet even with these risks, the opportunity outweighs the danger.

A country long denied its truth is finally witnessing it emerge and played out under the unforgiving light of public scrutiny. For a people taught to expect impunity, the sight of power finally answering to the law may be the beginning of something long overdue: the end of silence.

—

Omar Faris is a writer and an analyst