Now is the worst time for Bangladesh to cut its defense budget..but it did it, anyway

In a recent televised discussion, the press secretary to the Chief Advisor, Shafiqul Alam, issued a blunt charge: that the left in Bangladesh aims to keep the national economy “dwarfed.”

Though provocative, his comment gained added weight in light of an unprecedented development–yesterday’s announcement that Bangladesh’s defense budget would shrink for the first time in the country's history.

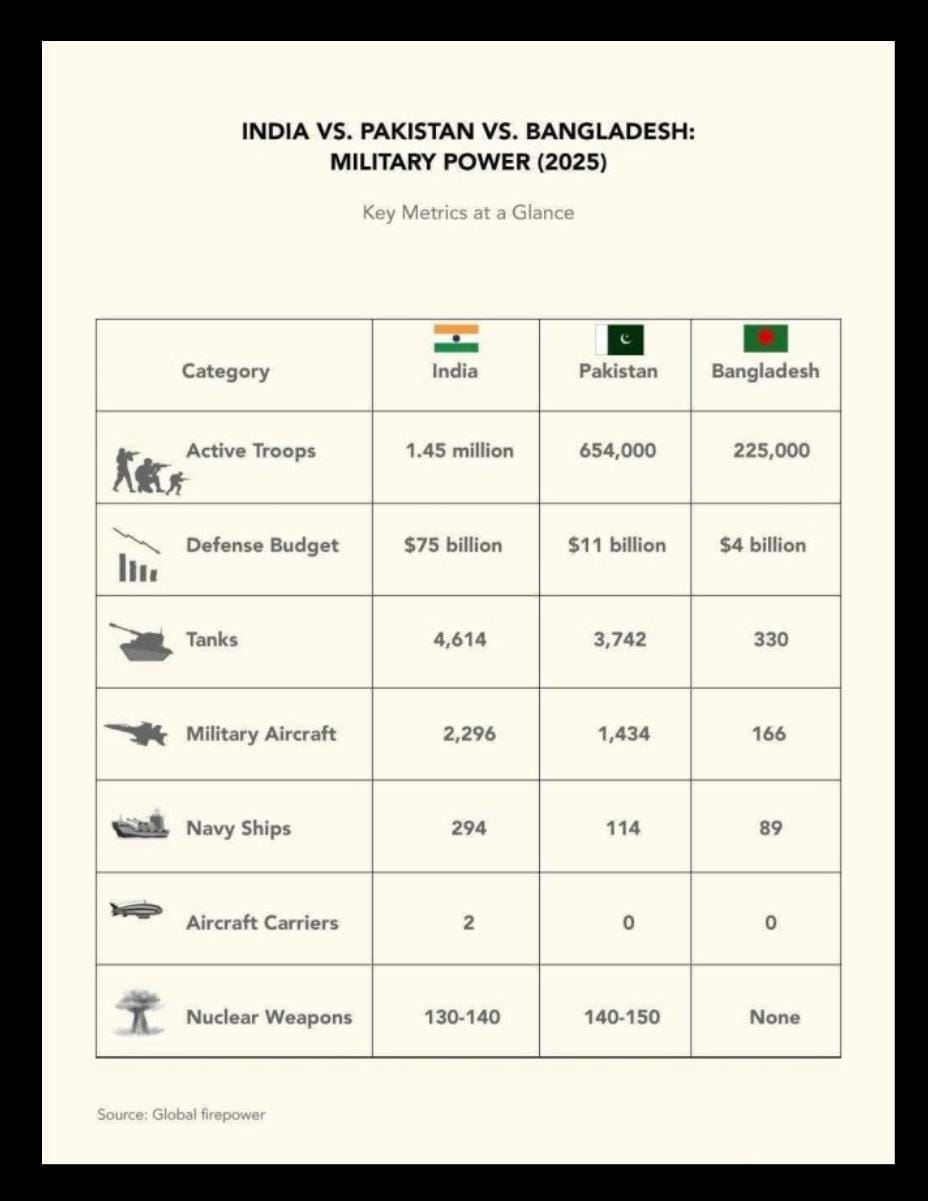

The proposed defense allocation for the fiscal year 2025–26 stands at 40,698 crore taka, down from 42,014 crore in 2024–25–a reduction of 1,316 crore. In ordinary times, such a move might be chalked up to fiscal constraint or shifting policy priorities.

But these are not ordinary times. With South Asia witnessing the most intense aerial combat between India and Pakistan since the Second World War earlier this year, the decision seems both symbolically and strategically dissonant.

This budgetary contraction arrives amid a broader debate–one that has simmered in academic circles and op-ed pages for years–over the role of Bangladesh’s military in national life.

Left-leaning voices, particularly in influential NGOs and editorial boards, have often questioned the need for sizable defense spending in a country where poverty, education, and infrastructure still demand urgent attention.

Such arguments are not without merit. But they risk tipping into idealism when they ignore regional geopolitics.

-683ed0aa88719.jpeg)

Bangladesh’s

defense capacity, by many accounts, is alarmingly underdeveloped. The nation’s

MiG-29 fleet, for example, lacks missiles–effectively rendering these fighter

jets closer to civilian aircraft than to combat-ready machines.

Out of 20 engines, only six are currently functional. Meanwhile, defense modernization efforts languish. Where India and Pakistan respectively dedicate 22% and 10% of their defense budgets to development expenditures–including procurement and upgrades–Bangladesh’s new budget allocates just 2.4%.

It is this gap–not merely in numbers, but in strategic thinking–that should trouble policymakers. Operational expenditures, including salaries and pensions, remain intact, aided perhaps by the populist legacy of ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina.

Yet in a region defined by rapid militarization and volatile diplomacy, failing to modernize may pose an existential risk.

A military in the shadow of Its economy

Bangladesh’s economic rise has been notable. With a GDP of approximately $460 billion in 2024, it now stands ahead of Myanmar and even edges past Pakistan. But unfortunately this economic progress has not translated into comparable military strength.

Bangladesh’s current defense budget–roughly $3.6 billion–amounts to just 1.02% of GDP. In contrast, Pakistan, with a smaller economy, allocates nearly $10 billion to defense.

Myanmar, despite its much smaller GDP of $65 billion, spends an estimated $2.4 billion–a figure representing nearly 4% of its output. The difference is more than arithmetic; it reflects differing assumptions about the role of the military in national survival.

-683ed0c5db383.jpeg)

Bangladesh

maintains a force of 163,000 active personnel. Myanmar fields more than twice

that number; Pakistan nearly four times. In terms of hardware, the imbalance is

more severe: Bangladesh has just 44 fighter jets, no attack helicopters, and

relies primarily on short-range missile systems like the FM-90 for air defense.

Pakistan, by comparison, deploys 387 fighter aircraft; India, which geographically surrounds Bangladesh on three sides, commands more than 600 fighters, including French-built Rafales armed with Meteor long-range missiles.

Bangladesh’s naval and armored capabilities are similarly modest, with only two submarines and a fleet of 13 surface ships.

Such limitations would carry grave consequences in a high-intensity conflict. Should a scenario akin to a hypothetical Indian "Operation Sindoor" unfold–a concentrated aerial offensive–the country’s ability to repel or deter aggression appears deeply insufficient.

Its current radar coverage and short-range missile defenses are not designed to withstand a sustained assault by modern, multirole aircraft operating with electronic warfare support.

Strategically, this raises an urgent dilemma. Without a credible deterrent–be it through nuclear alignment or a significant upgrade in air defense and strike capacity–Bangladesh remains dangerously exposed.

Procuring systems such as the Chinese FM-3000 or FK-3, modern fighters like the JF-17 or J-10, and long-endurance UAVs such as the Bayraktar TB2 or CH-4, would be a rational starting point.

But such a shift would require more than procurement; it demands doctrinal recalibration and, crucially, a sharp increase in spending.

-683ed0fac3a65.jpeg)

The cost of hesitation

To even begin closing the gap, Bangladesh must rethink the scale and structure of its defense priorities.

A defense budget fixed at just over 1% of GDP may reflect past political pressures or philosophical leanings. But in a region defined by asymmetry, inertia is no longer a viable strategy.

The path to a credible minimum deterrent is quantifiable. The acquisition of key air defense and strike systems, such as China’s FM-3000 (estimated at $50–100 million per battery), the FK-3 ($70–150 million), and multirole fighter jets like the J-10 ($40–50 million) or JF-17 Block 3 ($25–30 million), alongside proven UAV platforms such as the Bayraktar TB2 ($5–10 million), would require a targeted investment of approximately $1.5 to $2 billion.

This would support a modest but meaningful upgrade: a handful of batteries, a squadron of modern fighters, and a fleet of drones capable of reconnaissance and strike missions.

But hardware alone is not the full cost. Training, maintenance, logistics, and infrastructure–all essential for operational readiness–would push the total requirement higher.

A 40–50% increase in Bangladesh’s defense budget, bringing it to $5.0–5.4 billion (roughly 1.4–1.5% of GDP), would be a realistic figure to achieve these goals within the next two to three years, assuming disciplined procurement and some level of vendor financing.

This

estimate is not extravagant by international standards. In fact, it aligns

closely with Bangladesh’s own shelved military roadmap: Forces Goal 2030, a

modernization plan that has largely stagnated under the weight of economic and

political hesitation.

With regional neighbors investing heavily in defense technology, Bangladesh’s current trajectory risks strategic obsolescence.

Which makes the interim government's recent decision to cut the defense budget all the more puzzling. The move, reportedly directed under the watch of the defense minister and the national security advisor, appears disconnected from both regional security developments and the country’s long-term strategic posture.

The foundational obligation of any state is to survive. That is not to diminish social development, economic equity, or environmental stewardship. But without sovereignty, none of those pursuits can be sustained.

The recent India–Pakistan conflict underscored this in brutal clarity: in a neighborhood governed by hard power, soft power alone is insufficient.

Bangladesh’s economic ascent gives it the means to safeguard its sovereignty. What remains in question is whether it will find the political will to match its ambitions with the resources they require.

—

Dr Nirjhor Sakib teaches political science at University of Kentucky