Press freedom has turned into a tool for manipulation and misinformation by some media in Bangladesh 2.0

Bangladesh's press has shifted drastically, and not for the better. Under Sheikh Hasina's authoritarian rule, the media was stifled; journalists faced imprisonment, dissent was criminalized, and self-censorship was rampant. The alternative was to become a government mouthpiece.

Now, under an interim government, some media outlets have become reckless and irresponsible, operating with little accountability. In just two days, we've seen alarming instances of this malpractice.

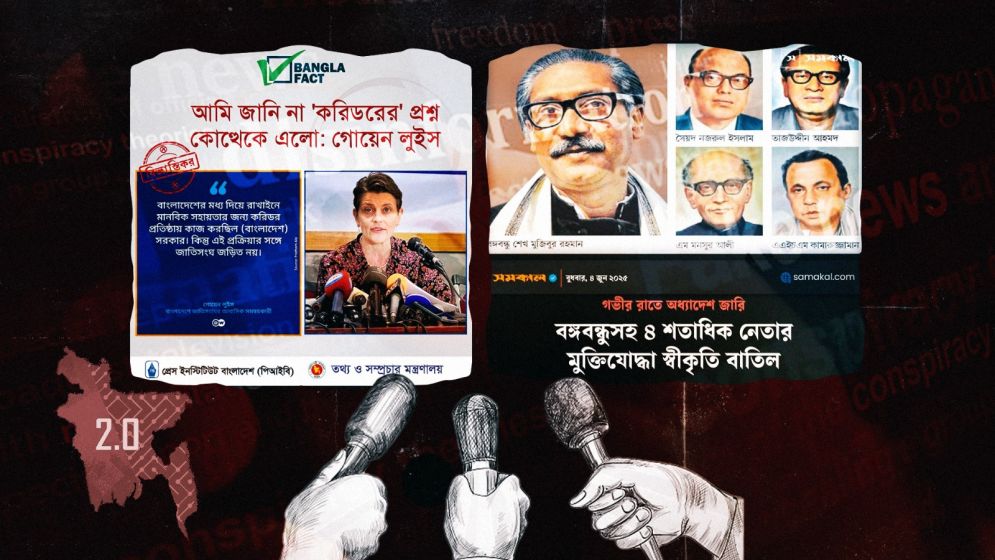

For example, DW Bangla recently published a now-deleted post falsely attributing a statement to UN Resident Coordinator Gwen Lewis. DW claimed Lewis said, "Bangladesh was working on establishing a corridor, but the UN is not involved."

However, Lewis never made this remark and clarified on June 4 that "no humanitarian corridor has been established, and we are not involved in any such discussion."

What Lewis actually said was that any humanitarian corridor would need formal agreements between sovereign states, a process in which the UN plays no part.

DW's misrepresentation wasn't a mere mistake. It served to echo a long-standing narrative pushed by Indian media, falsely portraying Bangladesh's international actions.

By the time DW blamed its local partner, Prothom Alo, and admitted the error, the falsehood had already spread widely, creating confusion instead of clarity.

While the Hasina government imprisoned journalists, criminalized dissent, and forced self-censorship, today's media, once stifled, has become its own adversary. It now engages in deliberate distortion and inflammatory rhetoric with little concern for the repercussions.

Another latest instance of this media malpractice seems like a calculated provocation. Several major Bangladeshi newspapers, some with strong links to the previous government, published a sensational headline claiming the recognition of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and other national leaders as "freedom fighters" had been revoked.

In truth, this was merely a bureaucratic reorganization of verification lists. Yet, these reports spun it into a narrative of national betrayal–a willful distortion designed to incite division and confusion.

To the casual observer, it might have seemed like the state was erasing history, but in reality, no such thing happened. Let's call this what it is: narrative vandalism.

Dilemma of the interim government

What's truly disturbing is that many of the outlets behind this distortion are the same ones that served as propaganda arms for the Hasina regime.

Some of their publishers, now fugitives from justice, continue to operate their editorial machines with alarming independence, churning out misinformation and outrage whenever it suits them.

These institutions weren't victims of the previous regime; they were its enablers. Now, free from government repression, they've misinterpreted freedom as a license to mislead, manipulate, and provoke.

Even more troubling is the growing suspicion that some of these media organizations are acting as conduits for Indian deep-state influence within Bangladesh. Yet, when faced with evidence or criticism, they offer no apology or correction–only silence or, worse, a defiant repetition of their false narratives.

So, where does this leave the public? They're caught in a constant state of confusion: silenced under the previous government, now manipulated by a press that has abandoned its duty to tell the truth for political drama and foreign interests.

The interim government has, commendably, shown restraint in the face of this chaos. Even with a legal framework inherited from the last regime that allows for strong action, the government has avoided cracking down.

Instead, it has issued warnings, performed its own fact-checks, and urged media outlets to make corrections. This approach is admirable, but the media's recklessness can't go unaddressed indefinitely.

And here's the irony: if the interim government does decide to act against these irresponsible outlets, they'll undoubtedly seek refuge behind international groups like Reporters Without Borders–organizations that are conveniently silent when media platforms are abused for personal or foreign political gain.

Press freedom isn't a free pass for spreading misinformation. Everyone must be held accountable, especially those who claim to speak truth to power while actively creating confusion and chaos.

A prime example is the recent protests by government secretariat employees against logical reforms–changes necessitated by their abuse of privilege. Despite no political party supporting these protests, the media continues to amplify them, pushing an agenda that traps the public in confusion and discord.

The same holds true for the press itself. With the exception of a few student voices, no political party has endorsed the reckless narratives these outlets are pushing. Yet, they persist, fueling chaos and division for reasons that remain unclear but are certainly not in the public's best interest.

Caught between a rock and a hard

place

Ultimately, Bangladesh is caught between two extremes: a press that swung from being stifled to completely unhinged, and a government trying to balance restraint with the critical need for accountability.

How much longer can the public tolerate this dangerous game of misinformation before it's too late to correct course?

The fact is, this crisis didn't appear overnight. Today's press is a direct result of 15 years of a media culture defined by distortion, submission, and political subservience. For a generation of reporters, truth was stifled, spin was celebrated, and loyalty to power was the sole guarantee of survival.

For some, this is all they've ever known, and it shows in the shoddy, irresponsible reporting now saturating our airwaves and digital platforms. This is precisely why senior editorial leadership must step up.

They know better. They've been around long enough to understand that journalistic credibility isn't a luxury; it's the bedrock of public trust. They have a duty to steer the ship back on course.

If these senior editors fail to instill a new ethic–one grounded in accountability, transparency, and professionalism–they won't just risk irrelevance; they'll guarantee their descent into oblivion.

In this age of social media and digital-first consumption, reputations unravel quickly. These outlets are already facing scorn and mockery, not from internet trolls, but from frustrated and less easily manipulated readers.

Their once-loyal audiences are waking up and no longer buying the spin. The public is watching, and they're growing weary of these games.

In an era where information is abundant and citizens can access alternative sources with a few taps, the only thing standing between legacy media and irrelevance is public trust.

If the media continues to churn out misleading, sensationalized, or poorly sourced content, the audience will simply tune out–or worse, turn against it. It's a perilous game, and Bangladeshi media outlets are playing it at their own peril.

–

Omar Faris is a writer and an analyst