Tarique Rahman turned diplomacy into a democratic breakthrough with a pen, two books, and an hour-long dialogue

On August 5, 2024, a nation shackled by over a decade of authoritarian rule finally exhaled. Bangladesh, long hostage to the iron grip of autocratic ruler Sheikh Hasina’s increasingly fascist regime, erupted in a historic uprising–one that cost lives, but reawakened a people.

For 15 years, the Awami League ruled by coercion. The machinery of the state–from courts to security forces–was turned inward against its own citizens. Political opposition was criminalized, dissent brutally crushed.

Even children were not spared; five-year-old Riya Gope, a member of the minority Hindu community, was among those killed, allegedly under Hasina’s direct command during the July-August uprising. Enforced disappearances became chillingly routine. Bangladesh was suffocating.

But on that August day, the tide turned.

A broad-based people’s movement–encompassing students, youth groups like Chhatra Dal and Jubo Dal, and all major opposition parties, especially the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)--surged forward to dismantle the status quo.

Their demand was simple: an end to authoritarianism, and the restoration of democracy.

Following the fall of Hasina’s regime, an interim government was formed through political consensus. Yet uncertainty started to hang over the country. While the interim administration held symbolic promise, its tenure remained undefined.

And while Tarique Rahman, exiled BNP leader and son of former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia, had offered full support to the interim government, the public’s patience started to wear thin.

This is because, Bangladeshis have been denied the right to vote in a fair election for nearly two decades. Now they want the full measure of justice–a credible election and the prosecution of those who looted their future.

And at the forefront of people’s fight for restoring democracy, stands Tarique Rahman

Rahman is not an outsider to this fight. He entered politics in 1988 from Gabtali, Bogura, rising quietly but steadily through the BNP’s ranks.

He played a behind-the-scenes role in the 1991 elections that unseated the military regime of Hussain Muhammad Ershad and brought his mother to power–the country’s first female Prime Minister.

Refusing high posts in favor of grassroots activism, Rahman became a tireless organizer, launching the now-famous "Union Representative Conferences," traveling from village to village, listening, organizing, mobilizing.

It was this grassroots momentum that unnerved the Awami League. Their support was eroding under the weight of their own misgovernance, frequent strikes, and growing public frustration.

Rahman became the target of state-sponsored propaganda, a scapegoat in a country craving reform and a restoration of democracy.

-684fb327e6b5b.png)

Fighting against a robbed democracy

The Awami League, throughout its tenure, abandoned even the pretense of democratic engagement. Its strategy was simple: crush dissent, suffocate the opposition, and maintain power through orchestrated chaos.

Strikes, propaganda, and politically motivated violence became daily weapons in their arsenal. On October 28, 2006, the brutality turned fatal–a BNP activist was bludgeoned to death with logi and boitha, traditional boat oars turned into tools of political murder.

That descent into disorder gave the military its opening. An army-backed caretaker government stepped in, ostensibly to restore order. But instead of correcting course, it predictably sharpened its knives against BNP’s rising figure–Rahman.

He was arrested, tortured, and left physically impaired. His crime? Becoming a threat to the Awami League’s monopoly.

After relentless public pressure and grassroots mobilization, Rahman was finally allowed to seek medical treatment abroad in September 2008. But his exile only deepened his resolve.

A decade later, in 2018, Begum Khaleda Zia– the BNP’s matriarch and former Prime Minister– was jailed through a sham trial in what was widely condemned as a political hit job.

Hasina’s kangaroo courts were in full swing. In her absence, Tarique Rahman formally assumed the role of acting chairman. And he did not retreat into symbolic leadership. He got to work.

Despite being in exile, he remained intimately connected to BNP’s grassroots– from senior leadership to local union organizers. When an activist was jailed, he personally intervened. When a family was harassed, he responded.

In contrast to the soulless bureaucracy of the Awami regime, Rahman offered human presence–even from thousands of miles away.

It is this model of leadership that Hasina feared most.

The 2018 election was not just rigged–it was stolen in the dead of night. Ballots were stuffed before dawn. Observers were blocked. Opposition agents were arrested. The so-called “night election” was democracy in a body bag.

By 2024, Hasina tried it again–this time with new tricks. She invented two puppet parties, Trinamool BNP and BNM, to mimic opposition voices and lend credibility to yet another rigged process. But no one bought it. Not the people, not the media, not the international community.

The Awami League had once again underestimated the strength of the BNP under Rahman. What they found was not a fractured opposition, but a movement consolidated like a pyramid–strong at the base, unshakeable at the top.

So, when Professor Muhammad Yunus was appointed to head the interim government following the collapse of Hasina’s regime, hopes soared. Both Khaleda Zia and Tarique Rahman were welcomed as figures of legitimacy and reconciliation.

Yet as weeks passed, the interim administration drifted from its core mandate: election reform, justice for the oppressed, and national healing.

Instead of laying out a roadmap to free and fair elections, the government veered into political abstractions. Public impatience began to simmer.

That’s when Rahman–the man once imprisoned, maligned, and exiled–stepped forward again. On June 13, 2025, he walked into a London hotel lobby with quiet authority and a minimalist delegation.

There was no theatrical showmanship, just the precision of a statesman.

-684fb34b00f97.jpeg)

The fateful London meeting

He extended his hand to Professor Yunus. “I feel honored,” he said. It was a gesture both symbolic and strategic–signaling openness, humility, and a readiness to lead with civility.

When he followed with, “The weather is friendly today,” it wasn't idle small talk. It was an invitation to turn the political climate at large–from confrontation to construction.

Sometimes diplomacy isn’t brokered by treaties or backroom deals, but by gestures–subtle, deliberate, and rich with meaning.

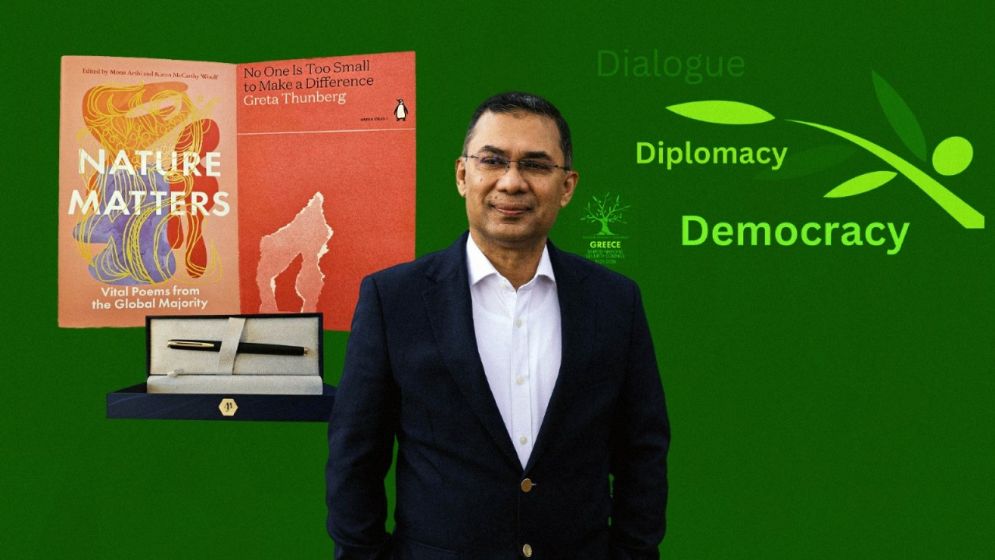

At their meeting, Rahman came bearing gifts: two carefully selected books and a pen. It was, symbolically and strategically, a masterstroke.

Yunus, a Nobel laureate and global advocate of the “three zeros”-- zero poverty, zero unemployment, zero net carbon emissions–is as much a man of ideas as of action. He reveres books. Rahman knew this.

His first gift, No One Is Too Small to Make a Difference by Greta Thunberg, signaled something deeper than shared environmental concern. It reflected Rahman’s own evolving leadership–conscious, globally attuned, and focused on generational responsibility.

He had already promised launching a nationwide tree-planting campaign, a move rare in a region where environmental policy is often an afterthought.

The second book, Nature Matters: Vital Poems from the Global Majority, edited by Mona Arshi and Karen McCarthy Woolf, was more poetic–literally. It spoke to resilience, diversity, and the power of unheard voices.

It was a message to the country: that those once silenced will be central to the new Bangladesh.

A pen, of course, was the final piece–as a challenge more than a token: the time to write a new chapter had arrived.

Over years in exile, Rahman has transformed. No longer simply the heir to a political dynasty, he is now a tactician armed with policy, presence, and patience. He doesn't just make demands–he builds consensus.

That June meeting, once seen as a gamble, turned into a turning point.

The result? A consensus for a national election, finally scheduled for February 2026. After two stolen elections, years of political repression, and untold sacrifices, the people of Bangladesh will return to the ballot box.

It was a win–for the people.

Rahman, reading the public mood with clarity and conviction, knew this was the moment to act. His message after the meeting was clear: “Shobar Age Bangladesh”--Bangladesh First.

For too long, Bangladesh’s politics have been about survival. Now, for the first time in a generation, they may be about hope.

—-

Salahuddin Ahmed Raihan is a civil engineer. You can reach him at [email protected]