Hasina’s law enforcers told me they’d kill me….like it was a mundane routine….

-6866a3abbafff.jpeg)

In the first week of July 2016, I was deep in the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest, swallowed whole by humidity, tiger trails, and silence.

My phone was useless–no signal, no calls, no news from the outside. I was stationed there for two weeks as part of a USAID-funded training project, working with frontline staff from the Forest Department.

It was the kind of assignment that pulled you away from everything: family, headlines, politics–especially politics.

After those two weeks in the forest, I was scheduled to return to Khulna City, where the second leg of my assignment awaited. I’d stay another two weeks working from the office. For me, it was more than a job. It was a lifeline. One more chapter in the long, grinding effort to reclaim a life the state had tried to erase.

On the 14th day–mid-morning, midsummer–we were pulling out of the jungle by boat, heading toward the dock at Nilkudumur in the Satkhira range.

As we inched back toward civilization, my phone caught a signal. Usually, the phone explodes with missed call alerts once I reenter coverage. But this time, the call came through immediately.

It was Sub-Inspector Rahmat from the Police Special Branch in Mirpur. A seasoned officer with nearly three decades in uniform, Rahmat had been assigned to my case. That’s how it works in Bangladesh when you're classified–unofficially, but unmistakably–as a state enemy.

Since the Pilkhana massacre and its political aftershocks, the Hasina government had made it policy to monitor, marginalize, and humiliate anyone who didn't fit the narrative. Men like me had officers like Rahmat assigned to us like shadows.

But Rahmat had always been different–polite, even respectful. At our first meeting, he made a point of telling me: “Sir, I worked with Kahar Akand on the Pilkhana investigation. I know the file. I know why you're here. And I swear, I won’t harm you.”

He kept his word, mostly. That morning, still shaking off the mud and mist of the Sundarbans, I picked up his call.

“Assalamu Alaikum, Sir. Where are you? Why has your phone been off?”

The question struck me as odd. Rahmat knew my schedule. I had told him before I entered the jungle that I’d be unreachable for two weeks.

“I was in the forest, Bhai,” I replied. “No signal.”

His tone changed.

“Sir, have you seen the news?”

“No. I just got back to the network. I haven’t even opened my phone yet.”

“There’s been an attack. A big one. A terrorist attack at a place called Holey Artisan Bakery in Dhaka. Many people are dead.”

My chest tightened. “What are you saying?”

“It’s serious,” he said. “Very serious.”

No end to harassment

And just like that, I was no longer a trainer in the forest. I was a name again. A file. A suspect-in-waiting. The kind of person the government would look at sideways, especially in moments of national crisis.

The forest had released me. But the state never had.

“Oh, okay. That’s terrible,” I said, still processing the weight of Rahmat’s words. “I’ll check the news in a bit.”

He paused.

“So Sir, you were in the jungle, right?”

“Yes, Bhai. You know that. Why are you asking again?”

He hung up without another word.

I didn’t realize it then, but something was already in motion.

Over the following weeks, the outlines of a crude plot emerged–one meant to tie me, however tenuously, to the Holey Artisan attack. The logic was laughable. The desperation was not.

They tried, and they failed, because reckless loyalty to bad instructions only gets you so far. The architects of this smear–those “overly clever” types eager to impress their superiors–found themselves stuck. Their target refused to fit the frame.

But the fallout didn’t end with that botched scheme.

Inside the USAID project itself, another storm was brewing. An HR officer, who happened to be the sister of a military officer, made it her business to poison the atmosphere around me. She fed the management warped versions of my story, stoking suspicion, whispering innuendo.

Add to that the renewed police harassment–phone calls, drop-ins, questions without end–and by late August, my position in Khulna had become untenable.

I had already interviewed for a new job in Dhaka and received an offer. My time in Khulna was winding down. It was September 2016, my final stretch in the city, when SI Rahmat called again.

“Rajib Sir,” he said, “you’ll need to come to Dhaka. A few Sirs from the Special Branch want to speak with you.”

I asked why. He claimed not to know.

A familiar game.

Bending the laws

What authority did he even have to summon me from one division to another? Of course, no answer would follow. Just the usual line: orders from above. And I know exactly who ‘the above’ is.

I took leave from the project office and boarded a vehicle for Dhaka. The ferry at Mawa was choked with traffic, an endless snarl of trucks and exhausted drivers. By the time I reached the capital, dawn had broken.

I showered, changed, and dressed like a man going to an interview–because that’s what I told my family it was. There was no point alarming them. Why disturb the people who already worry about you every day?

Before I left, I messaged a trusted friend. I told him where I was going and what to do if I didn’t come back.

Not that it would have made any difference. The last time I disappeared, nobody could help.

At 10 a.m., I arrived at the local Special Branch office. SI Rahmat was waiting by the gate, stone-faced. He led me inside without much small talk. I sat alone on a bench outside a small, locked door. The clock ticked louder than usual.

Minutes passed.

Then Rahmat returned, opened the door just slightly, and said, “Sir, go in. They’re ready for you.”

I entered the room. It looked like any other drab government office–pale walls, a rickety fan, the faint smell of dust and cheap furniture polish. Three men were seated. The man in the middle had a desk in front of him. The other two sat on either side, chair-only.

That was the power dynamic–center stage belonged to him. The others flanked him like footnotes.

They all stood as I entered.

“Assalamu Alaikum, Sir,” the man in the middle said with a tight smile. “We’re sorry to bring you here all the way from Khulna. Thank you for coming.”

There was a courtesy in his voice–but it was too measured, too rehearsed. It wasn’t politeness; it was performance. Something in me went stiff. I didn’t return the greeting. I didn’t speak. I just nodded and sat down in the chair they pointed to, directly across from them.

“We’re officers of the Special Branch,” the man continued, as if that needed clarification.

Still, I said nothing. I didn’t even look up. I kept my eyes on the table between us, half-expecting the varnish to crack from the tension in the room.

“Let’s not waste your time,” the officer said. “We’ll get straight to it.”

A pause.

“Sir, we’ve received orders from above. We will kill you.”

For a few seconds, I thought I hadn’t heard correctly. The sentence floated there, unnatural in its calmness. I stared at the floor.

Then he said it again.

“We will kill you. Just like your officer–Major Zahid–was killed. You could be next.”

Later, I would learn they were referring to Major Zahid, a retired officer gunned down by the CTTC, reportedly under the direction of DB Monirul. That was the subtext. The not-so-subtle comparison. A preview of the page they might copy.

A chill passed through me, but not for long. Just a second. Then, clarity. Then breath.

“Do you have anything to say?” one of them asked.

I lifted my head. Slowly.

No country for a law-abiding men

Memories hit like blunt force: Pilkhana, the years of surveillance, the interrogations, the betrayals, the people I loved who vanished or were taken, and my own relentless attempts to rebuild a life inside the margins of suspicion. I had lost too much to flinch.

And so I looked the man in the middle in the eye.

“This country,” I said, “doesn’t belong to anyone’s father. My father is a freedom fighter. He didn’t give his blood for a country where you can threaten his son like this. This is my country too.”

There was a brief flicker of uncertainty in his expression. Maybe no one had ever said something like that to him before. Or maybe he just didn’t expect it from me.

I didn’t stop.

“Tell your superiors I’ve seen enough in this life. I do not fear death. And I will not leave my father’s country. Not for anyone. Not for anything. Do what you’ve come to do.”

They had no reply.

Without a word, one of them gestured toward the door. The meeting was over.

I stepped out into the thick Dhaka air. SI Rahmat stood on the sidewalk, face drawn, eyes lowered. He looked like a man carrying the weight of things he couldn’t say. The weather matched his mood–grey, heavy, mournful. The kind of day where nothing feels resolved.

I nodded. Said nothing. And walked away.

What I didn’t know then was that the Special Branch had recorded everything–my words, my refusal, my defiance. It was all written down, sealed into a file.

I found out nearly two years later.

And then, life moved forward–or pretended to. A lot has happened since. But this isn’t the place for all of that.

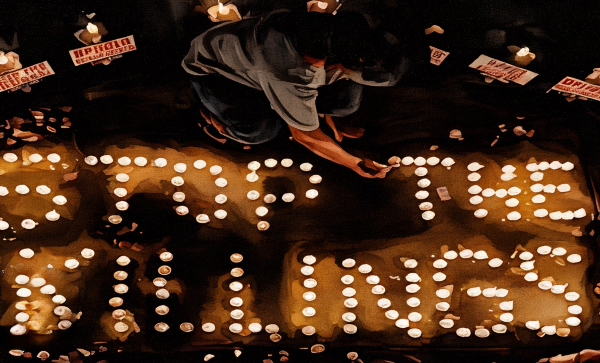

Almost eight years later, in 2024, the fire returned–not in me this time, but in the students of Bangladesh. They rose in protest against the same system, the same inherited arrogance, the same regime that tries to crush anything it can’t control.

One night, I sat watching the television, and I heard them chanting in the streets:

“Bought with the blood of millions of martyrs,

This country is not anyone’s father’s.”

I smiled. Not because of joy. But because I recognized it.

That moment in the Special Branch office–my words, spoken in the face of a quiet death threat–came flooding back. And I realized something simple, but undeniable:

Wherever people are pushed to the wall, the language of resistance is always the same.

—-

Rajib Hossain is a former army officer. He is the founder of Bir Muktijoddha Khandaker Abu Hossain Memorial Girls' School