Why is proportional representation too risky for Bangladesh’s fragile democracy?

The recent clamor from fringe elements like Jamaat-e-Islami and the nascent National Citizen Party (NCP) for Bangladesh to ditch its first-past-the-post electoral system in favor of proportional representation is, at best, a naive misreading of our political landscape, and at worst, a cynical ploy to legitimize their own irrelevance.

While the siren song of "inclusivity" and "multiparty participation" might sound appealing in theory, a cold, hard look reveals this proposition to be utterly impractical and ill-suited for Bangladesh's current political reality.

Proportional representation, in its purest form, promises a legislature that mirrors the nation's diverse political opinions, theoretically allowing every vote to count. But Bangladesh is no theoretical utopia.

We are, for all intents and purposes, a two-bloc state, firmly entrenched in the rivalry between the Awami League and the BNP-led alliances. Voters here align with these formidable forces, viewing smaller parties not as independent entities but as mere appendages or adversaries to the dominant poles.

To suggest that introducing PR would suddenly birth a vibrant tapestry of diverse voices ignores the uncomfortable truth that most minor parties in Bangladesh are either proxies, satellites, or opportunistic alliances – utterly devoid of genuine grassroots support or independent voter bases.

Embracing PR now would not foster true diversity; it would merely offer a veneer of legitimacy to fragmented, unrepresentative groups, quite possibly fanning the flames of the very political divisions that have plagued our history.

Furthermore, the integrity of any electoral system hinges on the strength and impartiality of the institutions overseeing it.

Proportional representation, with its intricate vote counting, allocation, and seat distribution mechanisms, is inherently more vulnerable to manipulation where oversight is weak.

Bangladesh's Election Commission has, for too long, grappled with a crisis of public trust and perceived independence. To burden such an institution with the labyrinthine complexities of a PR system is to invite disaster.

Moreover, PR often necessitates the backroom dealings and opaque negotiations inherent in forming coalition governments.

In a still-developing democracy like ours, this fertile ground would undoubtedly breed horse-trading, vote buying, and cronyism, eroding the very democratic principles these parties claim to champion and further alienating a public already wary of the political process.

This is a recipe for deeper disillusionment.

The misguided comprehension

The current advocacy for proportional representation in Bangladesh, emanating from the political fringes, is not merely misguided; it’s a dangerous proposition that threatens to plunge our nation into an abyss of governmental paralysis and societal fragmentation.

To embrace such a system now would be to deliberately undermine the very stability crucial for navigating the profound challenges confronting Bangladesh, particularly in the tumultuous wake of the post-2024 political uprising.

A proportional representation system, by its very design, almost guarantees fractured mandates, yielding fragile coalition governments perpetually mired in parliamentary gridlock and policy stagnation.

This is a luxury Bangladesh simply cannot afford.

Our nation demands decisive executive authority to implement critical reforms, a clarity of purpose that the current first-past-the-post system, despite its imperfections, largely provides through clearer mandates for winning parties.

Shifting to PR would invite an era of chronic instability, hobbling our capacity to address pressing national issues and pursue essential long-term development plans.

Moreover, the insidious allure of proportional representation in socially diverse or politically charged environments lies in its potential to empower fringe elements. It can grant parliamentary seats to parties with narrow, even divisive agendas, affording them national influence grossly disproportionate to their actual popular backing.

Imagine, then, the consequences for Bangladesh: religious extremist groups, insular regional identity movements, or even thinly veiled family enterprises masquerading as political parties could gain a dangerous foothold in our legislature.

In a nation where the social fabric is already taut with the stresses of authoritarianism and repression, such a development would inevitably escalate sectarianism, inflame communal tensions, and unleash an unprecedented wave of political instability.

Bangladesh’s delicate social and political equilibrium is perilously ill-suited for the ideological fragmentation that a PR system would undoubtedly accelerate.

The practicalities of implementing such a complex system are equally daunting.

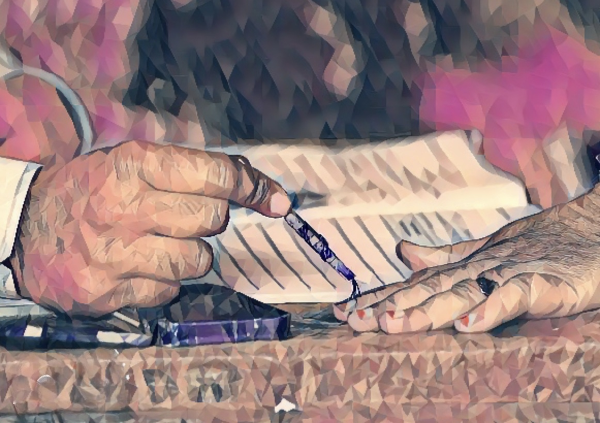

Proportional representation demands a sophisticated level of political education and engagement from its electorate, requiring an understanding of convoluted concepts like party lists, quota calculations, and indirect representation.

In Bangladesh, particularly in our vast rural areas, political literacy remains woefully limited. Our voters resonate with individual candidates and their local presence, not abstract party lists or national vote percentages.

A sudden, ill-conceived pivot to PR would not only breed widespread confusion but also alienate a significant portion of the electorate, ultimately diminishing voter participation and ironically undermining the very inclusivity it purports to champion.

This is a direct route to chaos and further disenfranchisement than to a path to democratic enlightenment.

Lack of electoral credibility

The cynical push for proportional representation in Bangladesh, emanating from the very fringes of our political landscape, reveals less about democratic idealism and more about the proponents’ own glaring lack of electoral credibility.

Let us be clear: for many advocating this drastic shift, the demand for PR is a transparent gambit to secure parliamentary seats without the arduous, inconvenient work of cultivating genuine grassroots support or winning the confidence of a constituency.

This isn't a principled stand for democratic reform; it's a self-serving shortcut to power, a desperate attempt to legitimize political irrelevance without earning it.

Such transparent ulterior motives cast a long, dark shadow over the entire proposition, confirming that this is not a well-considered blueprint for the nation's democratic future, but rather a cynical maneuver designed for individual gain.

While Bangladesh undeniably stands in dire need of electoral reform – a desperate cry for democratic legitimacy and inclusion after years of autocratic suffocation – the wholesale embrace of a proportional representation system is a perilous misstep.

It is fundamentally ill-suited to our volatile political culture, our strained institutional capacity, our urgent governance demands, and our precarious security environment.

The solution for Bangladesh does not lie in this chaotic leap into a system that promises only fractured governance and heightened instability.

Instead, our focus must be on reinforcing the very foundations of our electoral process: demanding greater transparency, meticulously leveling the playing field for all political actors, and forging an election administration utterly devoid of partisan taint.

Rather than a reckless plunge into the unknown complexities of pure PR, a more pragmatic, evolutionary approach is warranted.

This could involve a refined first-past-the-post model, perhaps integrating elements like runoff voting to ensure majority representation, or even cautiously exploring mixed-member systems that judiciously combine constituency-based representation with a compensatory proportional element.

Such a measured, context-aware progression offers a far more stable and viable pathway towards a genuinely robust and democratic future for Bangladesh. Anything less would be an act of profound political irresponsibility.

—

Dr Faysal Kabir Shuvo is a Sydney Based data professional and urban planner, he writes on urban planning and development as well as political issues.