Awami League’s shameless logic reveals its deeper contempt for basic human agencies

In the political lexicon of Bangladesh, few words are more misused–or more weaponized–than “progressive.”

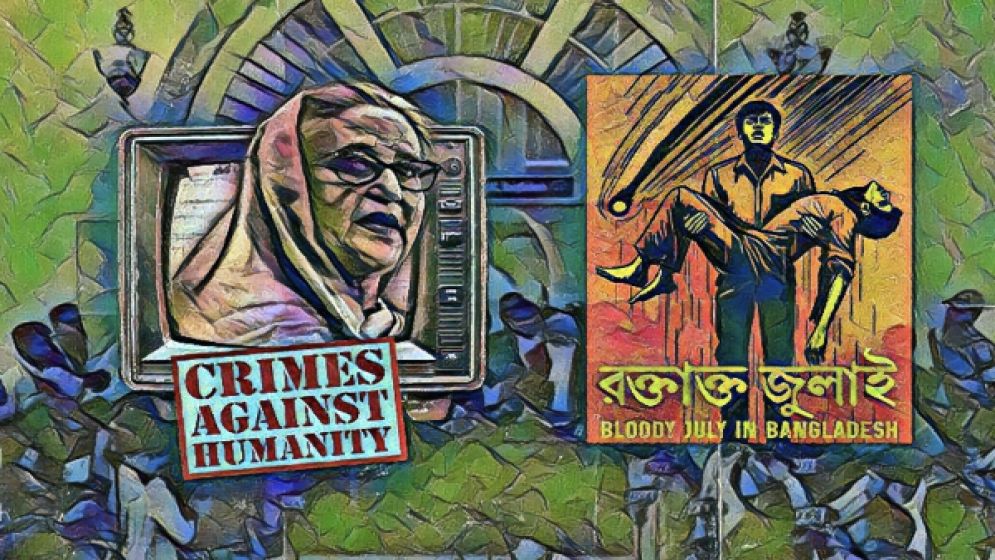

The deposed Awami League has long styled itself as the guardian of secularism, the Liberation War’s legacy, women’s rights, and modernity. But behind this polished narrative lies a deeply troubling contradiction: a consistent record of authoritarian practices, justified under the banner of protecting these very ideals.

Even among those within the Awami League’s own ranks, there is an unspoken understanding that the convicted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina ordered crackdowns like the one at Shapla Chattar in 2013, where security forces violently dispersed thousands of demonstrators.

While rarely spoken aloud, many educated, urban Awami League supporters defend the operation, insisting it was necessary to prevent the rise of religious extremism. Without such a response, they say, Bangladesh could have “become another Afghanistan.”

It’s a familiar pattern. The defense of human rights abuses is cloaked in the language of necessity.

Supporters of Awami League often offer two lines of reasoning. First, they argue that every political party, if given the chance, would behave similarly to retain power. Second, they claim that the Awami League’s ideological mission–secularism, women’s empowerment, development–is too important to be constrained by democratic norms or rights protections.

These violations, they imply, are unfortunate but permissible, even righteous. Yet these justifications fall apart under scrutiny.

Take the party’s record on sexual violence. Allegations of rape involving Awami League affiliates are disturbingly common. A simple online search yields story after story–many verified, others unresolved–linking party figures to horrific crimes.

Still, the party continues to present itself as the defender of women’s rights, a paradox it rarely feels compelled to explain.

Then there’s the matter of minority rights, particularly for the Hindu population. Land seizures in districts like Gopalganj–many allegedly orchestrated by figures close to the party elite–have gone largely unpunished.

land appropriated from Hindu families by former police chief Benazir Ahmed in a single sweep surpassed what rival political actors had taken over decades. And yet, Awami League apologists insist the party is the last bulwark against communalism.

It’s simply moral blackmail masquerading as progressiveness.

A convoluted narrative

The Awami League has attempted to conflate multiple ideas–liberation values, women's empowerment, secularism, economic development–into a single political identity, and then argue that this identity is inseparable from their party.

To oppose them is to oppose progress. But in no democratic society can real progress exist without human rights, without accountability, without the right to vote freely and safely.

What Bangladesh faced for a long time, and to this day, is not a clash between progress and extremism. It’s the monopolization of moral authority by a morally vapid party that refuses to be held to the same standards it demands from others.

Its most fervent supporters operate as disciples of a political faith–where Sheikh Hasina’s decisions are treated as infallible, and dissent is heresy.

Real progress requires more than slogans and historical credentials. It demands the courage to hold power accountable–even, and especially, when it wears the mask of virtue.

But perhaps the most dangerous justification offered by the Awami loyalists is not political–it is psychological. It is rooted in a deep, long-standing contempt for the very people they claim to serve.

This worldview treats ordinary Bangladeshis as an unruly population incapable of self-governance–people who must be subdued, not empowered.

This isn’t new. Phrases like “Bangabandhu brought independence to an unwilling nation” or “a freedom fighter is not always a freedom fighter, but a Razakar is always a Razakar” have long circulated in political discourse.

These are way more than just some harmless slogans. They are designed to belittle dissenting voices, especially among those who fought for the country’s liberation but dared to challenge the Awami League’s monopoly over that legacy.

The goal was pretty simple: to reduce the political consciousness of the Bangladeshi people to a stunted, manageable form–a kind of ideological bonsai.

-6872897ece53a.png)

The fault lines and snags

That attitude extends beyond party lines. I have witnessed segments of the Indian political establishment mirror this dehumanizing view, treating Bangladesh as a client state whose people require “strong-handed” leadership to prevent chaos.

Whether stated explicitly or hinted at diplomatically, the underlying message is the same: Bangladeshis cannot be trusted with freedom.

In this worldview, Sheikh Hasina became more than a political leader–she was the only figure deemed capable of maintaining order, no matter the cost.

Her authority, even when used to suppress dissent or authorize violence, was rationalized as a kind of paternal necessity. Her directives, however ruthless, were seen as corrective–benevolent even.

This belief system made debate futile. There was no need, her supporters argued and still do, to prove anything with evidence–no leaked phone call or report is required to justify harsh tactics.

They already know what she’s capable of. And they approve. Not in spite of the brutality, but because of it.

At its core, this logic is anti-democratic. It replaces rights with obedience, and citizenship with submission. And it leads to a profoundly unsettling question–one that is rarely asked, but urgently needs to be: if these ardent supporters believe that others do not deserve human rights, do they believe they deserve them for themselves?

And if not, what truly separates them from those they demonize?

The strength of a democracy lies in the dignity it affords its people, not in the perfection of its leaders, but. When a [former]government–and a segment of society–begins to view its citizens as less than fully human, it undermines not only justice but the very foundation of nationhood.

Bangladesh’s future cannot be built on the assumption that some lives matter less than others. No amount of historical symbolism or progressive rhetoric can justify that.

—

Mahmud Dhrubo is a Germany-based Bangladeshi writer