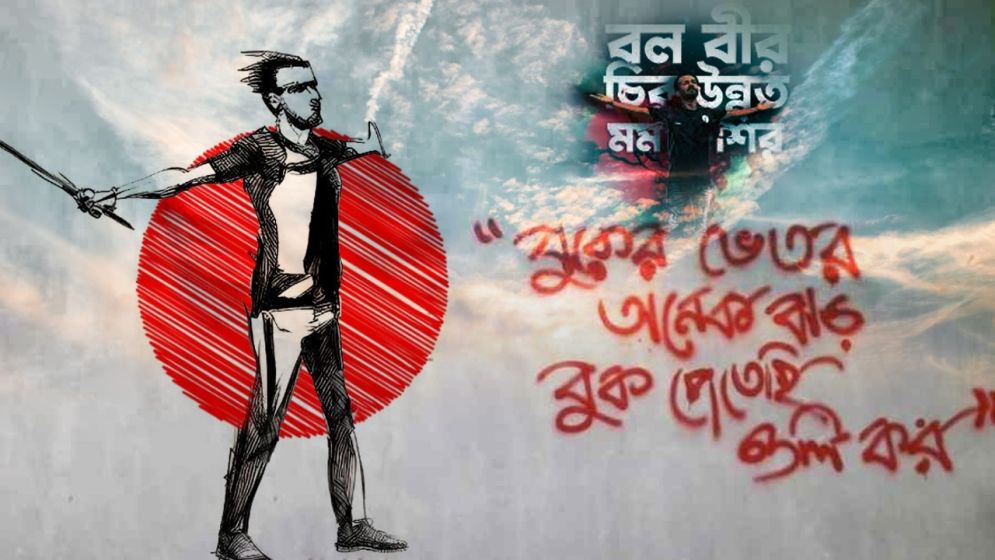

Crowned by the People, Abu Sayed has already become our new “Bir Shrestha”

In July 2024, Abu Sayed stood before the armed machinery of the state–unarmed, arms outstretched–and was gunned down. He was a student. He was part of a mass movement.

And in that moment, he became something much larger than himself: a symbol of defiance. A symbol of courage. A symbol the state could not control.

But symbols that emerge from the people are dangerous to those in power.

That’s why, in the days following his death, State Minister Mohammad Ali Arafat dismissed Abu Sayed as a "drug addict"--a desperate attempt to tarnish a sacrifice too powerful to erase.

That attempt, echoed by a chorus of sneering voices, reveals something deeper than personal malice: it reveals panic. When the public begins to define its own heroes, the state grows uneasy.

And when the people’s heroes expose the failure of those in power, the state lashes out with character assassination.

To some, it seems intolerable to speak of Abu Sayed in the same breath as the martyrs of 1971 or 1952. I’ve been condemned for doing so. But why? What is it we’re so afraid of seeing clearly?

In 1952, five young men were killed in the fight to make Bangla the language of the land. Today, we revere Salam, Barkat, Rafiq, Jabbar, and Shafiur. But the truth is, not all of them stepped out that day intending to become martyrs.

Jabbar, a man from Gafargaon, was in Dhaka to seek treatment for his mother-in-law. He saw a protest in front of the Medical College, joined in, and was shot. Shafiur Rahman, a court employee, was cycling to work when police bullets found him. He wasn’t waving a flag or chanting a slogan–just commuting.

So, if two out of five didn’t arrive at the protest as political actors, does that diminish the meaning of their deaths?

Of course not.

History doesn’t remember them because of their intentions; it remembers them because their deaths became part of a collective cry for justice.

Their lives were interrupted by a brutal state–but it is precisely that interruption, that transformation of the personal into the political, that made them martyrs.

And so it is with Abu Sayed.

The significance of Abu Sayed’s death

His blood stains the street, but his name now fills the air. It belongs not to the Ministry of Information or the official textbooks, but to the people. Those who insult him–mock him–aren’t just attacking his character.

They’re trying to control the story. They’re trying to reclaim the power to define who gets to be a hero.

But that power is slipping away.

When a state's legitimacy shatters on the chest of an unarmed boy, and that boy becomes a global symbol of resistance, no slander can put the pieces back together.

Let them try. We’ve seen this before. But history always remembers.

What ultimately matters is not where a martyr was going, but what their death meant–for the movement, and for the people.

In that light, is Abu Sayed’s sacrifice somehow lesser than that of Jabbar or Shafiur Rahman?

The politicians–those who orbit power like moths to a flame–sneer that “all this drama is for a job.” Even if we indulge that cynical claim for a moment, was Abu Saeed’s level of involvement in the July 2024 protests any less than Jabbar’s, who came to Dhaka seeking medical help for his mother-in-law, or Shafiur’s, who was simply cycling to work?

Let’s not pretend the desire for jobs is politically neutral. The demand for employment has been at the core of almost every mass uprising in this country, including the Language Movement itself.

To reduce that to “drama” is not just dishonest–it’s historically illiterate.

But the real discomfort for many doesn’t lie in Abu Saeed’s intentions. It lies in who gets to be remembered. For those who treat state-issued honors as sacred texts–untouchable, infallible–history may have even more unpleasant truths to offer.

Take, for instance, the 'Bir Bikrom' title, one of the nation's highest gallantry awards, meant to honor bravery during the Liberation War. But in post-1971 Bangladesh, this same title has been used to reward officers for leading military operations against Bangladeshi citizens–specifically, indigenous people in the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

Lieutenant General Chowdhury Hasan Sarwardy admitted publicly that he received the Bir Bikrom for his role in these operations.

Years later, the military itself declared him persona non grata in cantonment areas over his involvement in multiple unethical relationships as NDC Commandant. The ISPR later described his behavior as “embarrassing” to the institution.

Then there’s Major General Mia Mohammad Zainul Abedin, Sheikh Hasina’s former military secretary. He too was honored with Bir Bikrom for operations in the Hill Tracts. And Brigadier General Mozaffar Ahmed, another awardee in 1981, received it under similar circumstances.

What does it say about our national conscience when medals meant to honor liberation from oppression are handed out for enforcing internal repression?

When the same symbols that once represented resistance are rebranded to reward obedience?

It says that “heroism” is not just remembered–it’s manufactured. It’s distributed and withheld based on political convenience. The state’s version of valor is rooted in utility rather than justice.

Abu Sayed is indeed a “Birsreshtho”

Abu Sayed’s death wasn’t useful to the state. It was inconvenient.

It exposed something the government would rather keep hidden: that even today, unarmed youth are still dying for justice. That is why they call him a junkie. That is why they ridicule his memory.

But history doesn’t answer to power. It answers to truth. And no amount of slander will erase the fact that, in July 2024, a young man stood up and the state pulled the trigger.

The people remember. And they will continue to.

If leading military operations against unarmed indigenous communities in the Hill Tracts can earn someone the title of “hero,” then of course the idea of calling Abu Sayed a Bir Shrestha–the highest honor–will strike a nerve among those who benefit from the existing order.

It’s more of an exposure than just discomfort..

The people laughing at the suggestion of Abu Sayed being called Bir Shrestha aren’t just mocking a fallen student. They’re denying a fundamental truth: that heroism does not require the stamp of a government gazette, a salute from the parade ground, or a mention in a state textbook.

When an unarmed young man bares his chest to the rifles of an autocratic regime, he is not waiting for approval from the government. He is speaking in a language more powerful than decrees and titles–the language of resistance.

And in doing so, he becomes a symbol far more potent than anything the state can manufacture.

That is what terrifies the ruling class.

They want control over memory. Over the narrative of who gets to be remembered, and why. That’s why the attacks on Abu Sayed’s character–the smears, the innuendos, the allegations–have been so loud, so desperate, and so coordinated. It is not just an assault on his memory. It is an act of narrative containment.

But Abu Sayed is not a story they can contain.

His death didn’t occur in isolation. It happened in the context of a people’s uprising, a student-led movement that challenged authoritarian rule. His final stance–arms spread wide in defiance–was not a private moment.

It was a public rupture. And that rupture has entered the bloodstream of a generation.

Characters like Abu Sayed are born not in press briefings or war rooms, but in the collective conscience of a people pushed too far. That is why the elite class will never accept him. Because he represents what they cannot control: a hero born outside the script.

Martyr Abu Sayed’s death reminds us of a truth long buried under medals and protocol: that real heroism emerges in moments of crisis, not in peacetime ceremonies; from the streets, not from parliament.

Abu Sayed is our Bir Shrestha–not because the state said so, but because the people already have.

—

Arif Rahman is a writer