In Bangladesh, power is a racket disguised as governance

If you want to convince someone in Bangladesh never to have children, there’s a simple solution: sit them down in front of the government’s birth registration portal. That experience alone should cut the national birthrate in half.

Let me explain.

My son is now over two years old. I’ve spent months trying to secure his birth certificate. But the system demands my own birth registration number before I can proceed. I provide it–digitally registered, government-issued, seemingly valid.

The system rejects it. Why?

Because my data, like millions of others, has not been uploaded to the "central database." The local ward councilor responsible for updating it disappeared after the August 2024 upheaval. No one knows where he is.

So now, to register my son, I must start from scratch and get a new birth certificate for myself.

But to do that, I must prove that the permanent address I've used my entire life is, in fact, connected to my father–through a passport, land record, or tax receipt. The burden of proof for one’s own existence has never felt so perverse.

Kafka would not have merely wept–he’d have deleted his entire bibliography in shame.

Still, this isn’t just about one dysfunctional website or a missing bureaucrat. The deeper rot is spelled out on the site’s own FAQ page. In attempting to justify this absurd process, it claims that the goal is to “build a national family tree.”

A noble ambition, perhaps–but laughable in context.

The government has no functional API systems to connect databases across departments. It has lost huge swaths of data. It has no meaningful cybersecurity infrastructure; citizen records are routinely leaked on Telegram channels.

This isn't obviously nation-building. It's harassment wrapped in digital theater.

Even the rules are arbitrary. During voter roll updates, the government suspends its own documentation requirements without warning. Sometimes you need a birth certificate; other times, an NID suffices.

The rules change not according to logic, but according to convenience–or more accurately, chaos.

A system designed for obstruction

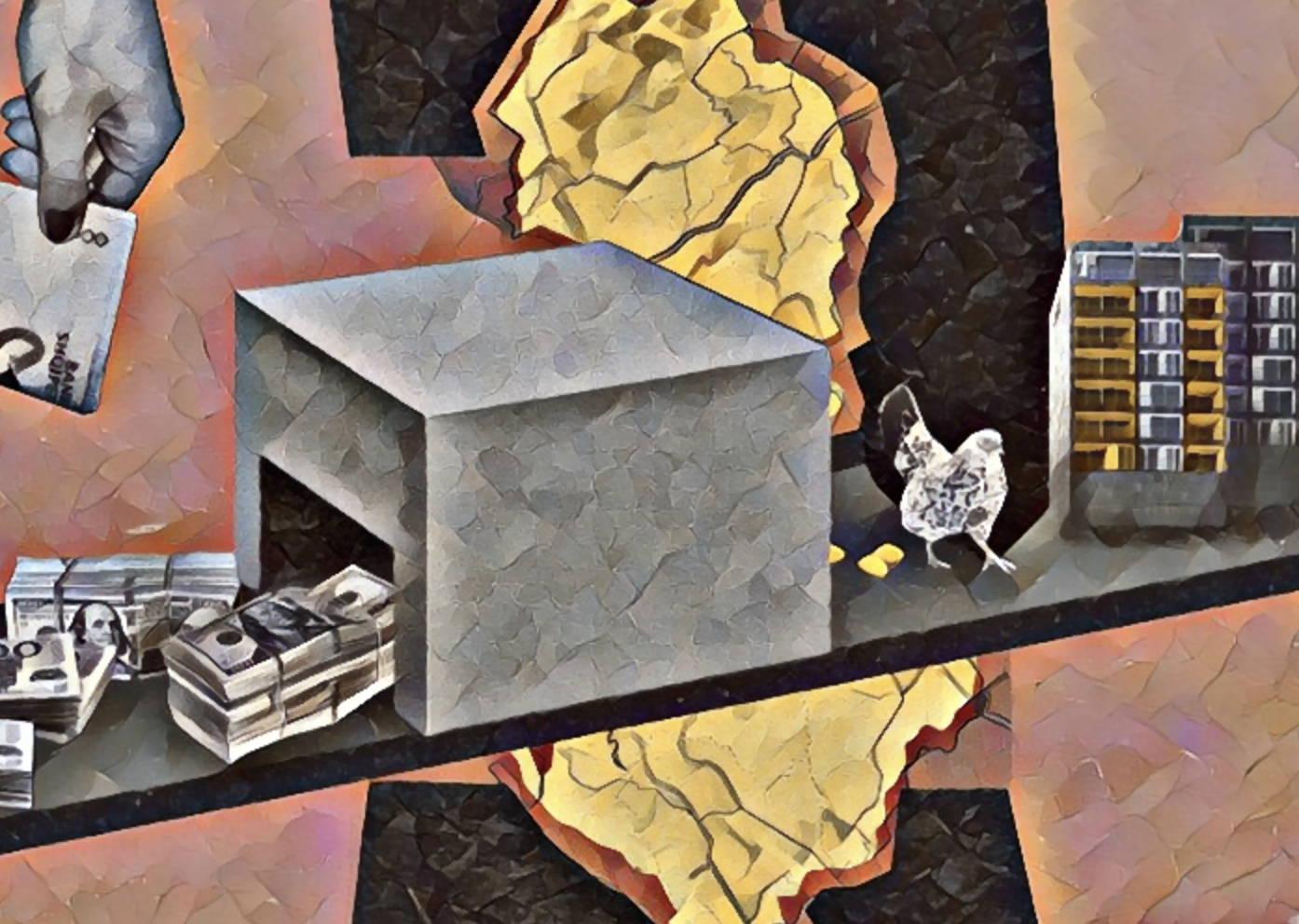

And that’s the real point: the system is built not to serve but to obstruct, so that it can sell you a shortcut.

The obstacles are intentional. The confusion is the product. The bribe is the only reliable service the state delivers.

Once you understand the logic of Bangladesh’s administrative structure–where citizens are told to input their data online only to later submit the same information offline on paper–you understand the essence of its politics.

The Bangladeshi state doesn’t function like a modern nation-state. It lacks the core attribute of statehood: a monopoly on legitimate violence.

It is powerless in the face of real threats–mobs, political thugs, extortionists–but quick to roar when faced with powerless citizens. It bows to power and crushes the weak.

And this dysfunction isn’t limited to public services. It defines the entire relationship between the state and its people. Instead of enabling productivity, the state’s primary function is rent-seeking. Citizens are treated like tenants.

To survive, you must pay–through formal taxes, informal bribes, and regulatory hurdles designed to punish efficiency. The laws aren’t written to maintain order; they are written to create bottlenecks.

If you follow the rules, nothing works. To get anything done, you must break them–and pay for the privilege.

And so, when we talk about the macro-level violence in Bangladesh–whether electoral manipulation, mob rule, or institutional breakdown–it makes perfect sense when viewed through the lens of something as seemingly mundane as birth registration.

These small indignities are more than just isolated frustrations. They are the administrative face of a deeper collapse.

The state may still exist on paper. But for ordinary people, it is experienced as a daily assault–by a structure that neither protects nor serves, but only extracts.

Method in madness

In Bangladesh, those fortunate enough to pass the Bangladesh Civil Service exams–or those with enough cash or political connections to bypass merit altogether–secure a place in a vast, parasitic machinery that quietly siphons the lifeblood of the working public.

For everyone else, especially the ambitious or desperate, the only path left is politics: not as a vocation, but as a gamble.

Politics here isn’t about ideology or governance–it’s a race to seize control of the state’s extractive apparatus.

That foundational absurdity infects the rhetoric on all sides. Whether it’s the ruling party’s surreal ambition to map citizens’ ancestry through birth registration databases, or the opposition’s hollow talk of nationalism, sympathy-driven mobilization, or "new settlements," it all reeks of the same farce.

Different actors, same stage, same script.

But while the spectacle may seem incoherent, it is anything but. Those in power–or those clawing their way toward it–have perfected the art of monetizing chaos.

Their strategies may appear deranged, but the logic is chillingly calculated. A few months ago, I wrote that by tolerating mob terror, the interim government was undermining its own sovereign authority, rendering foreign policy negotiation nearly impossible.

I thought I was witnessing incompetence. I was wrong.

What I failed to grasp then has become brutally clear now: the mobs were not a lapse in control, but a tool of it. Former Awami League leaders are now being shaken down–threatened with police raids or violent mobs unless they "contribute" funds.

The same tactic has surfaced among grassroots BNP activists. Instead of pursuing accountability for past state crimes or focusing on the July uprising, they’re busy filing baseless lawsuits–anonymous, often absurd–against small-fry actors.

It seemed senseless at first. But as investigative reports by Zulkarnain Saer have uncovered, this too is a racket: extortion dressed up as justice. Even furniture store owners on Panthapath are now being told they could be framed in the July murder cases–unless they pay up.

Like Polonius watching Hamlet unravel, we must look beyond the spectacle to find the system in the psychosis. There is always a money trail. And unless we follow it, we will never understand how power operates–not just in Bangladesh, but across much of the postcolonial world.

The political economy of the Global South cannot be studied in isolation from criminal enterprise. The lines between statecraft and racket have all but disappeared.

In that convergence lies the future–merely of any governance, but of survival.

—

Mikail Hossain is a writer and analyst