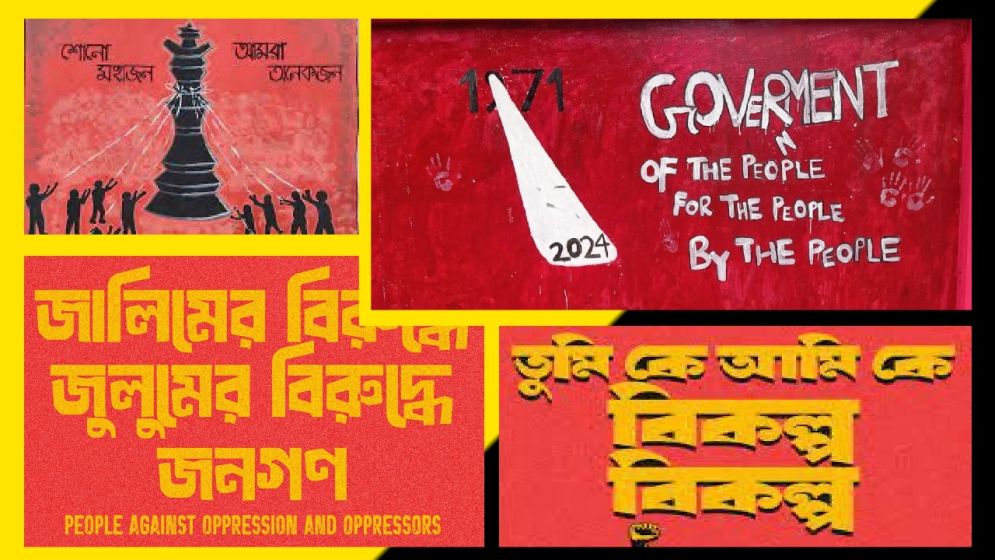

The ‘Long July’ was a movement led from below…and a warning to those at the top

In a country long burdened by manufactured consent and managed dissent, the uprising that unfolded last July in Bangladesh–now being referred to as the "Long July"--defied conventional political maneuvering.

What looked like a calculated opposition movement, or a top-down call to action, was in fact something far more organic and less orderly: a public-led rupture that outpaced its supposed leaders.

Given the state of fragmentation within and between Bangladesh’s major political parties, it would be naïve to describe the Long July as a masterstroke of party strategy.

This was not a carefully planned insurgency or a textbook revolution. Instead, it was a series of fortunate–and, to many, astonishing–events, driven by a groundswell of public participation that caught even the most seasoned political actors off guard.

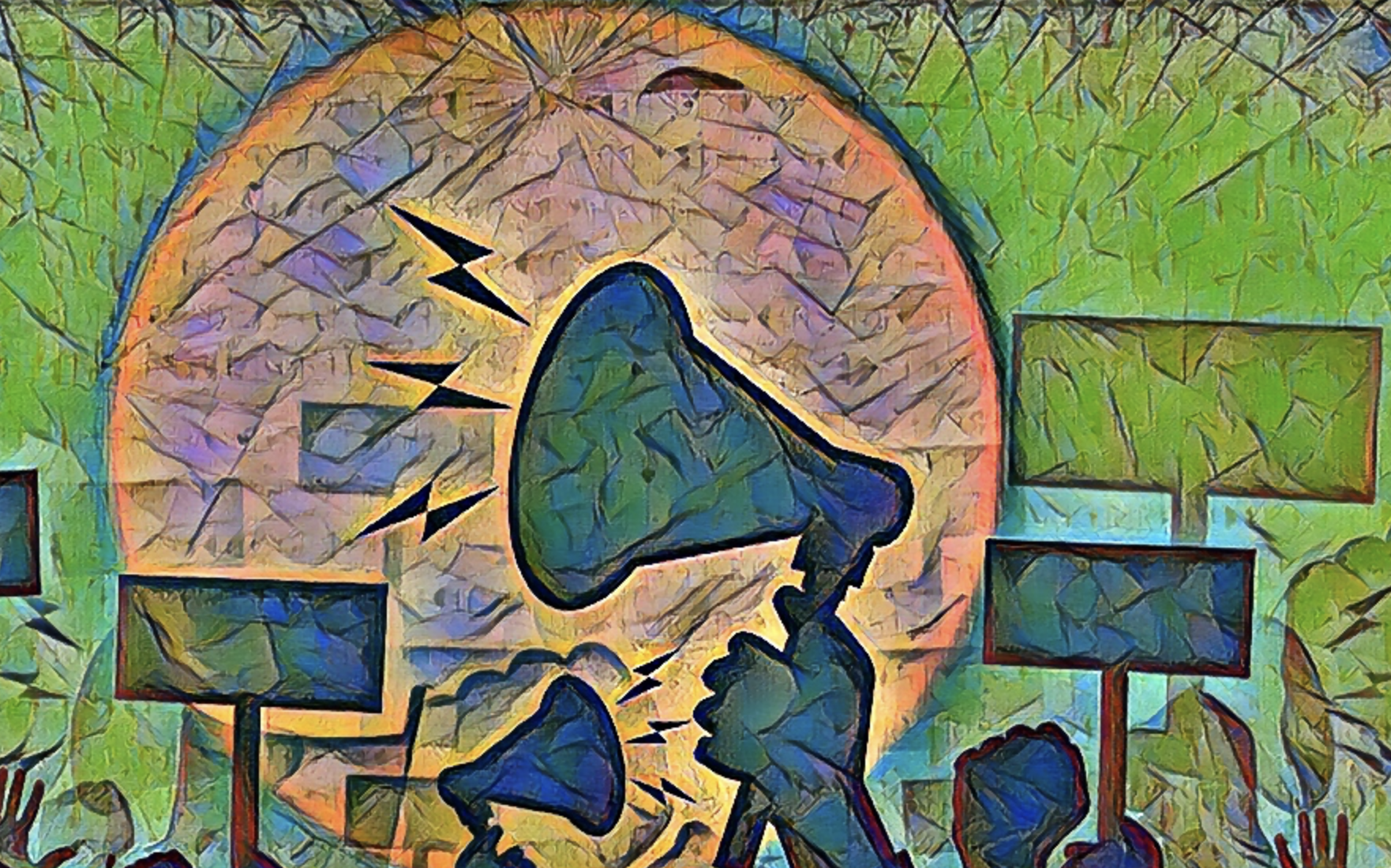

In truth, it wasn’t the leaders who led the people. It was the people who, through sheer will and momentum, forced the leaders to follow.

In the final days, the political figures who came to represent the movement functioned less as strategists and more as loudspeakers, echoing the sentiment already roaring through the streets: Hasina must go.

This inversion of leadership is critical to understand.

In the age of performative politics and centralized control, the July uprising offered a rare glimpse into a different political logic–one where collective emotion, moral exhaustion, and decentralized action became the primary engine of change.

Those who facilitated roadblocks, organized flash rallies, or even used state tools to enforce the people's demands may believe they were acting on independent judgment.

But strip away the layers of personal justification and one simple truth remains: they aligned, knowingly or not, with the singular pulse of the public mood.

And that mood was unmistakable.

After years of authoritarian entrenchment, rigged elections, targeted repression, and a surveillance state built with quiet nods from global backers, the populace reached a saturation point.

The breaking of fear happened not all at once, but in fragments–in whispers, in workarounds, in WhatsApp groups and ungovernable chants.

When the moment arrived, people didn’t wait for permission. They moved. The so-called leaders rather scrambled to keep up.

A pivotal point in our

history

So, in retrospect, the Long July may mark a turning point not just in the Hasina era, but in the architecture of power in Bangladesh.

The real actors were not seated at press briefings or backroom meetings. They were on the streets, in the bureaucracy, and even within the fraying apparatus of the state itself– quietly but decisively flipping the script.

The streets of Bangladesh told a truth no analyst or autocrat could deny: It wasn’t merely about electoral reform or civil liberties. It was about the people reclaiming authorship of their country’s future–and they were willing to sacrifice their blood, sweat, and tears to do so.

There was no convoluted ideological blueprint, no lofty theoretical jargon.

Just a single, visceral consensus: the Bangladesh that Hasina built–a tightly controlled state marked by mass surveillance, enforced disappearances, digital repression, and dynastic politics–could no longer be tolerated.

We have to remember that for over a decade, successive opposition efforts to challenge her rule collapsed under the weight of their own irrelevance. They misread the moment.

They mistook their slogans for strength, mistook international nods for legitimacy, and time and again failed to grasp what was missing: the people.

That’s what made the Long July different. This time, the masses moved first–and not with timid steps. They flooded the cities, occupied government precincts, and tore down the illusion of Hasina’s invincibility.

The opposition, disoriented by the very uprising they claimed to have incited, played catch-up– amplifying rather than organizing.

Yet even as the Hasina regime crumbled, another warning loomed: would this nascent revolution risk making the same mistake?

The euphoria of toppling a dictator often blinds movements to the very forces that brought them to power.

The early signs of post-Hasina politics already suggest a drift–negotiations behind closed doors, elite power-brokering, technocratic reshuffling–with the people once again pushed to the margins.

This should alarm anyone who cheered the uprising.

If the Long July was about more than just removing a despot–if it truly sought to build a republic–then excluding the public from what follows is not only hypocritical, it’s self-defeating.

The legitimacy of this transition rests not in how cleanly power changes hands, but in whether the people who bled for it are given a real stake in what comes next.

—

Nayel Rahman is a political analyst