The literary gaze of Humayun Ahmed’s unassuming brushstrokes…

By most measures, Humayun Ahmed remains the most beloved Bengali writer of the 20th century–a literary juggernaut whose novels, television dramas, and films rewired the cultural sensibilities of a generation.

But even for someone so prolific and versatile–author, screenwriter, director, lyricist, poet–there is one chapter of his creative life that remains largely overlooked: his paintings.

Yes, Humayun Ahmed painted, and painted seriously. And like many things about him, it was done without pomp, with characteristic restraint, and with that peculiar blend of childlike wonder and philosophical depth that made his writing unforgettable.

He picked up the brush in 1996, quietly, almost as a private experiment. He had long nurtured a deep admiration for visual art. His personal library included painting books–bought ostensibly for his children, but very much for himself.

Paint, painters, and the act of painting appear often in his fiction, tucked between sentences like familiar guests. Still, few expected him to produce original visual works, let alone nearly two dozen paintings in the final months of his life.

As he underwent cancer treatment in New York in 2012, Humayun found himself slowly withdrawing from the acts that once defined him.

"I used to read a lot of books in America," he recalled in an interview. "At one point I didn't like reading anymore. So I started writing, and that also became boring. Then I bought colors and started drawing one after another. I noticed incredibly good pictures being drawn.”

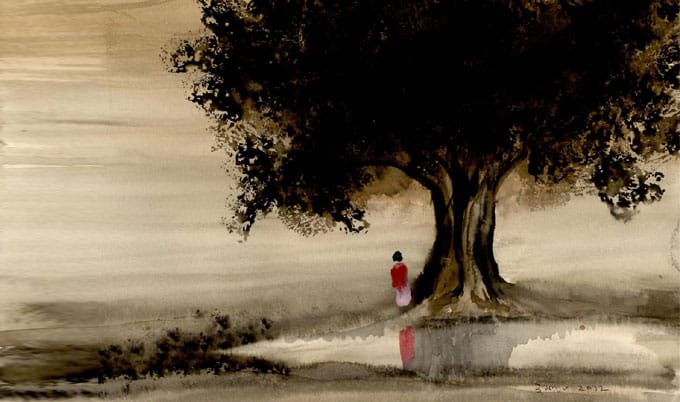

What he created–24 paintings, by the time of his death–were modest in technique but magnetic in feeling. Most bore poetic titles, echoing the lyrical sensibility of his prose.

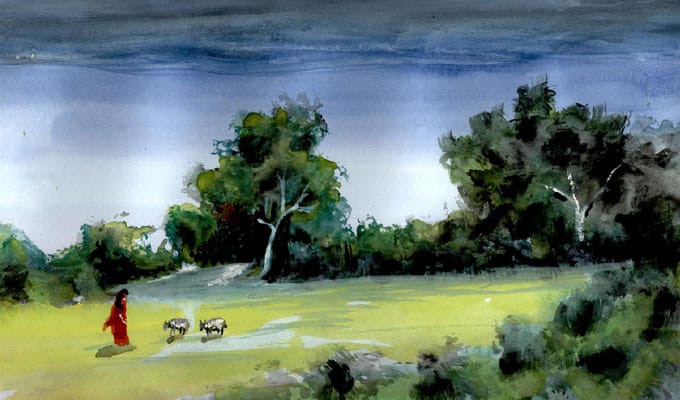

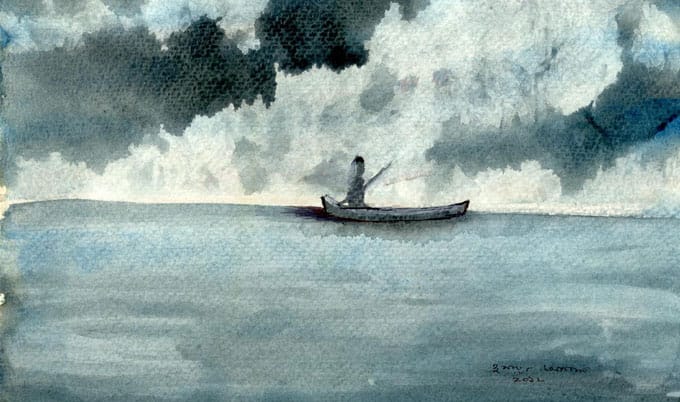

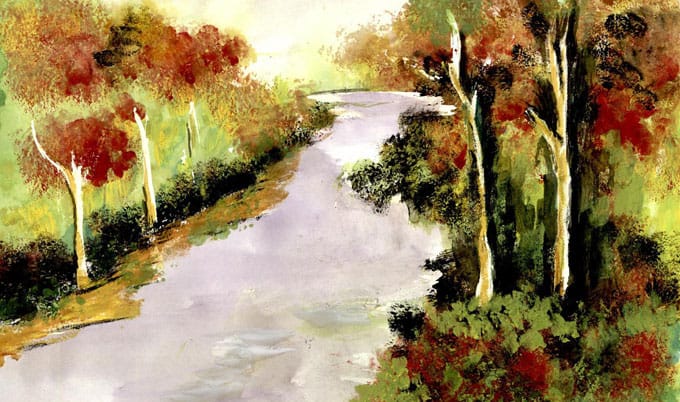

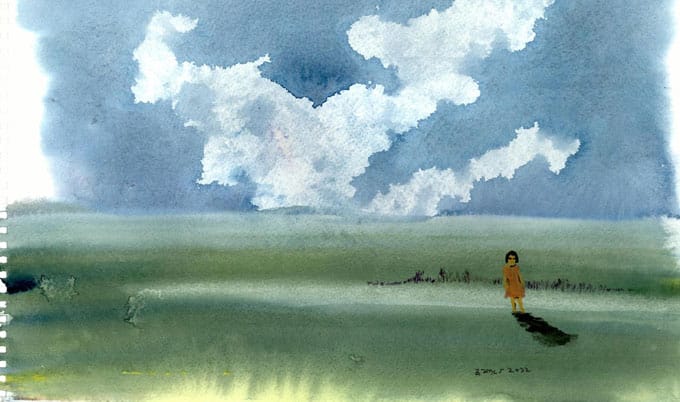

Trees, rivers, solitary figures, village paths–these were his favored subjects. In an era dominated by abstraction and hyperrealism, Humayun returned to the essentials: nature, solitude, silence.

“I broadly painted landscapes,” he said. “I didn't go to the abstract area. I would put on a stroke and it would be something huge–I am not into that. I am working with nature.”

It was a classic Humayun Ahmed statement: dry, plainspoken, and slyly defiant. He had no interest in posturing. He painted as he wrote–with an unfiltered ease, a conscious resistance to pretension.

In this quiet turn to painting, Humyaun found himself in the company of giants who also blurred the boundaries of their disciplines.

Rabindranath Tagore–his greatest literary influence–took to painting late in life, producing over 2,500 works. Jibanananda Das, whose poetic melancholy haunts much of Humayun's fiction, also left behind portraits and sketches.

For such polymaths, forms of creativity do not sit in isolation. They spill into each other.

Humayun’s paintings are not masterpieces in the academic sense. Some are technically uneven. But that hardly matters. They hum with emotional intelligence. They feel lived-in.

And they offer a final portrait of a man whose creativity, even in his final days, refused to be boxed in.

In the end, Humayun Ahmed didn’t paint to impress. He painted to feel alive.

But was it really that simple– this late-in-life embrace of art? Or did something more abstract stir beneath the surface of those soft, pastoral watercolors and stark, unpeopled landscapes?

Watercolor was his chosen medium. Most of his works were rendered on paper, with a few experiments in oil. He approached painting not as a prodigy, but as a disciplined student — methodical, deliberate, almost academic.

He began with still lifes, guided by instruction manuals and how-to books, then moved into landscapes. The result is an estimated 50 paintings, many of which he never signed, as if hesitant to fully claim them.

In 2012, shortly before his death, a small exhibition was mounted in New York–held over three days at the Muktadhara Book Fair, in a high school hall in Jamaica, Queens. Originally, 40 works were planned for display.

But in the end, only 20 made it to the walls. Some were unfinished. Others remained unsigned. Even in curation, he seemed to leave his art slightly ajar–incomplete, unsealed.

Two years later, in November 2014, the National Museum in Dhaka hosted a posthumous exhibition of his paintings and personal materials. This time, the public came for the quiet man with the paintbrush rather than for the writer or filmmaker.

Acclaimed artists who viewed his work praised its emotional clarity–a kind of visual storytelling that, like his novels, said much with little.

The brushstrokes were gentle but firm, the imagery stripped down, the mood often melancholic. There was no need to decode his intent; his paintings communicated directly.

They whispered loneliness, longing, and a solitary peace.

What made these works extraordinary was not technical mastery, but unmistakable authorship. The same voice that once created Misir Ali and Himu–eccentric, searching, heartbreakingly human–seemed to linger in these trees, these silent skies, these faceless figures.

It was art as extension of self. Not just the work of a novelist dabbling in another medium, but the full-hearted expression of an artist who had always refused to be confined to a single form.

In a world increasingly defined by noise, Humayun Ahmed painted with restraint. His painting, like his prose, was never in a hurry to impress.

It simply asked to be seen. And in doing so, it offered yet another reminder of why, in the universe of South Asian expression, he remains singular–and irreplaceable.

—

Sabiha

Nahla is an aspiring painter