Why Jamaat and Shibir should not be in politics

Bangladesh’s democratic politics has never been free of ghosts. And none looms larger than Jamaat-e-Islami and its student wing, Islami Chhatra Shibir.

Their presence is corrosive. They masquerade as political parties, but in truth they are ideological machines, built to destabilize the very societies they claim to redeem.

At the heart of Jamaat’s program is Islamism, an ideology that cloaks itself in the language of “true Islam.” But its real function is to divide.

By fusing religion with partisan ambition, it narrows the rich diversity of Muslim thought into a single suffocating mold. Those who dissent are branded as less pious–or worse, as traitors to the faith.

In a country as varied as Bangladesh, such exclusion is not just merely toxic, it is socially explosive.

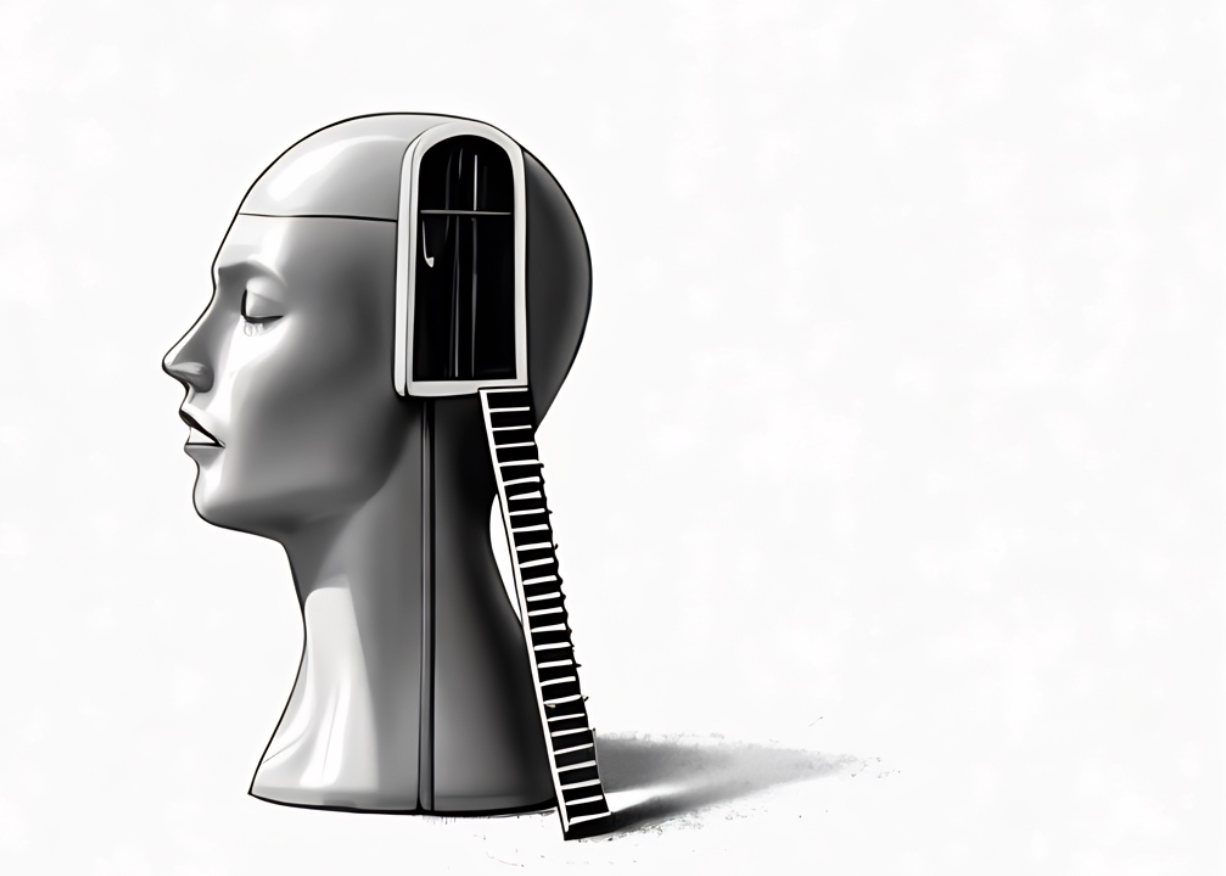

Jamaat’s danger, however, is not ideological alone. Its structure is Leninist in design: a vanguardist network of disciplined cadres, engineered for infiltration and domination rather than debate or compromise.

Unlike mass-based democratic parties, Jamaat thrives on control, secrecy, and near-military obedience. Electoral popularity has never been its fuel; coercion and pressure have.

Ironically, this has insulated it from the patronage politics and petty corruption that consume Bangladesh’s mainstream parties, making it a more efficient–if more insidious–political actor.

Its behavior follows this script. Jamaat and Shibir operate less like a party seeking votes than a pressure group intent on bending rivals to their will.

They insert themselves into the bloodstream of larger parties, shaping policies from within, amplifying their clout without ever winning broad democratic consent.

But the model is riddled with contradictions.

Traditional pressure groups maintain neutrality so they can whisper into the ears of all sides. Jamaat, by contrast, wants it both ways: to manipulate the mainstream while still contesting elections. That double role is untenable.

A battle within

Here lies the paradox: Jamaat might actually wield more influence if it shed the ballot box entirely.

Unburdened by the stigma of being a political contestant, it could embed itself deeper into Bangladesh’s party system, advancing its Islamist social programs without the baggage of open electoral warfare.

Indeed, the party has already softened its rhetoric, moving away from the most rigid strains of exclusivism.

What endures, though, is the damage its electoral presence inflicts: perpetuating the binary of Islamist versus secularist, a false dichotomy that continues to strangle Bangladesh’s democratic life.

Jamaat’s shadow lingers not because of its strength, but because Bangladesh’s democracy has never figured out how to step out from under it.

So long as Jamaat and Shibir insist on calling themselves political parties, they will remain trapped in the very polarization they helped create.

Their members are not, for the most part, career politicians. They are doctors, teachers, businessmen–ordinary professionals dragged into a political arena that brands them as extremists by association.

The irony is that most of Jamaat’s work–religious, cultural, educational, economic, charitable–exists outside the sphere of electoral politics. Yet by contesting elections, they inherit a political stigma that corrodes all these other efforts.

The truth is that Jamaat and Shibir are not parties in any democratic sense.

They are social movements with the instincts of a pressure group–disciplined, insular, designed to shape outcomes without the burden of winning a popular mandate.

That may be effective for lobbying, but it is toxic for democracy. A force built to pressure others cannot at the same time claim to represent the people.

And until Jamaat recognizes this contradiction, it will remain a destabilizing shadow in Bangladesh’s politics, never a legitimate participant in it.

—

Md Ashraf Aziz Ishrak Fahim graduated in Contemporary Islamic Studies from Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Qatar. Reach him at [email protected]