Justice for the disappeared requires respect for life

John Quinley and Saira Rahman Khan

Publish: 30 Aug 2025, 02:28 PM

Last year’s revolution in Bangladesh, bringing to an end Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s autocratic rule, has brought with it monumental reforms for democracy and human rights.

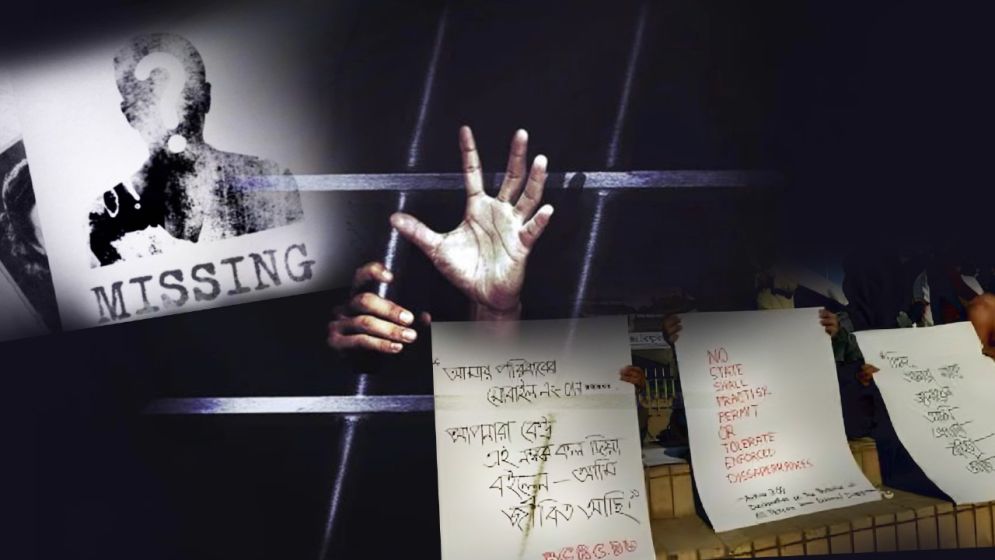

Yet, as we mark the International Day of the Disappeared today, August 30, hundreds of disappeared persons remain missing, and serious gaps prevail in ensuring fair trial standards and accountability for perpetrators of enforced disappearances.

After the Interim Government took office in early August 2024, its first human rights-related priority was to focus on the disappeared. Bangladesh signed the International Convention on Enforced Disappearance.

The Interim Government also established a Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances, led by retired judge Moyeenul Islam Chowdhury, to investigate the many hundreds of unresolved cases. By June 2025, over 1800 cases of disappearance were received by the Commission and it had investigated and verified 1350 of them.

Building on that progress, the government is now seeking to prosecute cases of enforced disappearance through the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT), a domestic court mandated to try serious international crimes, including crimes against humanity.

As a state party to the Rome Statute, Bangladesh recognizes that enforced disappearance constitutes a crime against humanity when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack on a civilian population, a pattern already confirmed by the Inquiry Commission in its investigation.

However, the ICT Act and the draft Ordinance on Enforced Disappearance Prevention and Redress raise serious human rights concerns. Both allow for the death penalty as a sentencing option and permit trials to be conducted in absentia—procedures that risk undermining fair trial standards and accountability.

Without bringing the perpetrators themselves before the judges, the fate of the disappeared may never be established.

-68b2b551bbaa3.png)

Furthermore,

the provision for capital punishment creates a glaring contradiction: while the

government pursues justice for grave human rights violations, it simultaneously

upholds a punishment that itself violates international human rights norms.

An accused faced with the possibility of receiving the death sentence may resort to denying any knowledge of the fate of a disappeared person. This not only delays justice but also prolongs the agony of family members, depriving them of closure.

There are, nonetheless, encouraging signs. The ICT has dedicated an entire investigative team to enforced disappearance cases, and the draft Ordinance contains promising provisions on reparations for victims and witness protection.

Human rights organizations, including Odhikar and Fortify Rights, have met with the Tribunal to raise objections to the use of capital punishment. We continue to support the ICT’s efforts to hold perpetrators accountable—both for the waves of violence during the mass uprising in July and August 2024, and for crimes such as enforced disappearances.

These efforts include the ICT’s issuance of an arrest warrant for former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and former Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal.

Despite growing international concern, a moratorium on capital punishment has not gained widespread domestic support. This is due in part to a prevailing demand for retribution, fueled in part by the anger over so many unresolved disappearances.

Even after Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s government was overthrown and she fled to India, student protesters continued to publicly call for her execution. In the past, the government of Bangladesh has always voted against the U.N. resolution for a moratorium on the death penalty.

However, in December 2024, the Interim Government changed the narrative and abstained. This is an encouraging sign, but it is a real concern that the retributive nature of a majority of society is what may stall any conversation on a moratorium.

-68b2b57969553.png)

Still,

there are voices within the movement calling for abolition. Barrister Mir Ahmad

Bin Quasem, who himself was forcibly disappeared for eight years from August

2016 to August 2024, has argued eloquently against the use of the death

penalty:

“The death penalty is irreversible. Anyone can muscle their way through the courts and use it. The lack of oversight and safeguards in the law makes it possible for the death penalty and the judiciary to become tools in the hands of a dictator. … But in this revolution, a moratorium on the death penalty must go hand in hand with a robust and sufficient reparations program.”

His words echo broader human rights norms. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Bangladesh is a state party, upholds the right to life. Article 6 of the ICCPR states, “Every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law.”

Rather than endorsing capital punishment as a means of accountability, the government should amend both the ICT Act and the draft Ordinance on enforced disappearance to ensure they are truly victim-centered—prioritizing reparations, truth-telling that provides answers about the fate of the disappeared, and justice for families and survivors.

As Bangladesh seeks justice for its past, it must not repeat the errors of decades of authoritarian rule and must focus on a new culture that prioritizes respect for human rights and human dignity.

Accountability must not come at the cost of fundamental rights. True justice demands not only trials, but fairness, dignity, and the abolition of state-sanctioned killing. The revolution may have opened the door to change; now its supporters and champions must walk through it.

—-

John Quinley is a director at Fortify Rights. Saira Rahman Khan is a professor at the School of Law at BRAC University and Secretary of Odikar.