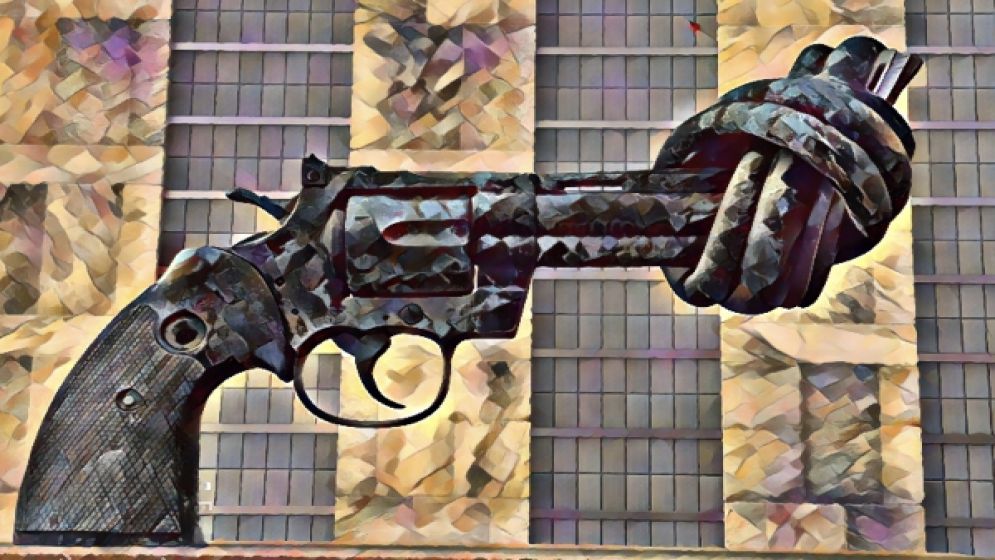

Symbolic violence and the inherent political message that it carries..

Violence is never just about the act itself. It is also about the spectacle. In the pre-Islamic era–the Jahiliyyah, or the “age of ignorance”--violence became a kind of social language.

A beating was always more than just a beating; it was a message broadcast to everyone else. One bloody body, one forced disappearance, could silence thousands.

Power, at its core, is the management of violence. It doesn’t need to strike every individual. It needs only to remind you, symbolically, of what it can do.

This is why symbolic violence so often eclipses direct violence in its impact. Machiavelli knew this. He warned that the fear of bloodshed exerts more control than blood itself.

Direct violence can be resisted. If someone raises a hand against you, you can strike back. But symbolic violence does its work before the blow ever lands. It erodes resistance in advance, training people to censor themselves, to live defensively.

Societies subjected to it find their intellectuals–those who should challenge power–beginning to echo it instead.

Pierre Bourdieu, the French sociologist, understood this dynamic. He showed how symbolic violence–whether through institutions, language, media, or culture–seeps quietly into daily life, shaping what people believe is possible, or permissible.

This is why the rule of law is indispensable in a democracy. Without it, coercion becomes culture, and development remains stunted. The politics of the jungle–the raw display of strength, the willingness to harm another body–has no place in human society.

The body is sacred. To harm it is to violate the very principle of being human. From the domestic sphere–when a spouse or a parent inflicts violence–to the state itself, every blow signals a descent back into barbarism.

The alternative is not weakness but care. Jacques Derrida called it hospitality, the radical openness to the other. Animals, too, sometimes display forms of care. But for humans, it is not an exception; it is a responsibility.

Care of the self, of one’s family, of one’s community, and of the world: this is the true cycle of human life. To give and to receive care is not just compassion. It is civilization itself.

Instinct and survival

If you live in constant fear that someone might beat you, bleed you, or kill you, then survival,not growth, becomes your only horizon.

Life turns into a cycle of anxious anticipation: strike before you are struck, dominate before you are dominated. But a society trapped in this logic of violence cannot nurture human development.

It remains chained to animal instincts, incapable of producing a truly advanced civilization. However deep the enmity, violence must never be allowed to take root. The only path forward is to reject it outright.

This is why dialogue–not force–must be the cultural foundation of a modern society. Violence belongs to barbarism, not to civilization.

And the rule of law is essential here. But law, too, can be corrupted. If it exists merely as an instrument of power, it ceases to be law and becomes another form of violence.

In such a system, people obey not out of trust but out of fear, and the line between justice and terrorism blurs.

The true purpose of law is freedom: to create conditions in which people can pursue their aspirations without trampling on the rights of others.

Law is meant to curb narcissism and authoritarianism–not to entrench them. A just legal system strengthens freedom by protecting the dignity of all.

An unjust one merely reproduces the same symbolic violence that it claims to prevent, leaving citizens subdued and fearful.

—

Rezaul Karim Rony is a writer and thinker. He is the editor of Joban Magazine