The statesman who gave Bangladesh a compass

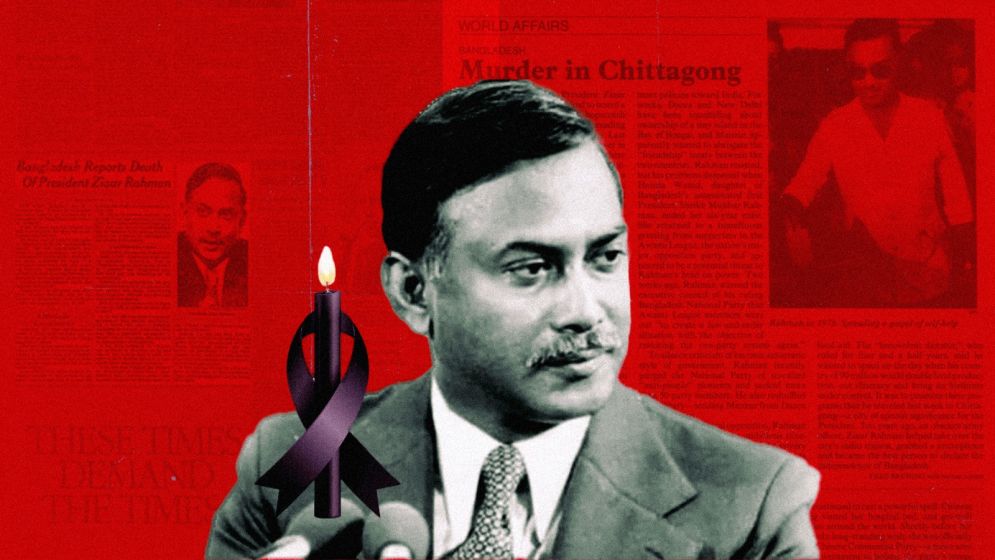

Forty-four years ago today, on May 30, 1981, President Ziaur Rahman was assassinated in Chattogram. What died with him was not merely a head of state or the founder of a political party.

What perished was something far more abstract–and far more potent: a myth.

In the chaotic aftermath of Bangladesh’s bloody birth, Zia was not just another military man thrust into political life. He was a figure forged by war, elevated by crisis, and obsessed–perhaps to a fault–with coherence.

Where others saw a country, Zia saw a case study in national psychology. And he tried to diagnose it.

But Zia’s legacy has long been reduced to the stale tropes of party politics: BNP versus Awami League, military strongman versus democratic legitimacy. These binaries are intellectually lazy and historically dishonest.

To understand Zia is to confront a far more unsettling question: What happens when a republic loses its sense of self–and who dares to give it one?

When a young Major Zia declared Bangladesh’s independence over a makeshift radio transmission in March 1971, it was an existential assertion. In a vacuum of authority, symbols matter more than signatures. And in that moment of psychic rupture, Zia became more a symbol of will than of legality.

The war ended, but the chaos did not. Bangladesh emerged physically sovereign but psychologically shattered. Institutions were either absent or imploding. The economy was rubble.

The identity of the republic hovered somewhere between linguistic nationalism and something far more ambiguous. Into this fog stepped Zia–as an architect of psychological scaffolding.

His concept of “Bangladeshi Nationalism” was more than rhetorical engineering. It was an ontological intervention. While Bengali nationalism clung to the romance of shared language, Zia’s project anchored the nation to territory and statehood.

It wasn’t about abandoning heritage–it was about including those never invited in.

Hill communities, Urdu-speaking migrants, Hindus, Buddhists–none of them found reflection in the cultural monoculture of Bengali identity. Zia, for all his flaws, understood what many of his liberal critics still don’t: A nation must accommodate its dissonances or risk becoming hostage to its own mythology.

Was this pivot political? Of course. But was it also philosophical? Undeniably. Isaiah Berlin’s “value pluralism” wasn’t in fashion in post-liberation Dhaka, but Zia practiced a crude, intuitive version of it nonetheless.

He offered not utopia, but alignment. Not purity, but structure.

A misunderstood statesman

His detractors call him a usurper. His supporters call him a savior. Perhaps both are right. But if we want to have an adult conversation about Ziaur Rahman, we must stop pretending that legacies are either sacred or damned.

They are, more often, sedimented contradictions.

Zia did not heal Bangladesh. He stitched it together–imperfectly, unevenly, but intentionally. And sometimes, in the life of a nation, that’s enough to matter.

The conventional critique of Ziaur Rahman rests on a question that is itself intellectually bankrupt: How can a man in uniform restore democracy? As if history doesn’t teem with military figures who stepped in not to dominate, but to stabilize.

The Weimar Republic emerged from military collapse. Atatürk dismantled an empire to birth a republic. In societies reeling from war, the line between soldier and statesman isn’t always a symptom of authoritarian drift. Sometimes, it’s a necessity.

Zia assumed the presidency at a moment when Bangladesh was closer to implosion than governance. He could have cemented a permanent martial order, turned the state into a personal fiefdom, and the people into subjects.

Instead, he lifted martial law, reauthorized political parties, and reopened the door to electoral politics. These weren’t the gestures of a man clinging to power–they were the maneuvers of a leader trying to haul a disoriented state back onto institutional rails.

Zia was no liberal in the Western sense. But he was a realist with democratic instincts. He understood that legitimacy, not just law and order, sustains a republic. Power, in his mind, was not an end–but a bridge.

His 19-point programme, often reduced to bureaucratic bullet points, was in truth a blueprint for national reimagination. It called for decentralization, rural development, and self-sufficiency–ideas that echoed the Gandhian vision of “village republics,” but filtered through the lens of a military man who had seen collapse up close.

Where others saw development as GDP figures, Zia saw it as dignity delivered locally–through canals dug, clinics built, and schools opened.

Was it populism? Perhaps. But let us not confuse accessibility with opportunism. Effective governance often lies not in lofty manifestos, but in the mundane. Zia grasped that governance must be felt in the grain of daily life.

A sack of rice, a functioning well, a village road–these were his currency of trust.

Architect of a stable future

Economically, his policies were foundational. In a donor-dependent state crippled by aid dependency and food insecurity, he championed self-reliance, private enterprise, and export-oriented growth.

The seeds of Bangladesh’s now-celebrated garment sector were planted under his watch. As Amartya Sen reminds us, “Development is freedom”–and Zia, imperfectly but deliberately, tried to tether economic progress to democratic form.

His turn toward Islamic symbolism–the insertion of Bismillahir Rahmanir Rahim in the Constitution, the language of Islamic solidarity in diplomacy–has drawn fierce criticism, often as evidence of ideological betrayal.

But such readings flatten the complexity of the moment. The late 1970s saw a global Islamic resurgence–from the Iranian Revolution to the reawakening of political Islam across the Arab world. Zia was was navigating it with his own vision.

To portray these choices as cynical pandering is to ignore context. In a region where secularism was increasingly equated with state failure, Zia recalibrated toward cultural legitimacy.

His use of Islamic rhetoric was strategic. It was a signal, not a surrender.

Zia’s contradictions remain. He was a military man who seeded democracy. A nationalist who courted pluralism. A secular tactician who spoke in Islamic idioms. But perhaps that’s precisely why his legacy endures: it resists simplification.

Bangladesh today stands on economic gains and democratic aspirations that, however fractured, trace back to Zia’s project of pragmatic nation-building. We don’t have to sanctify the man to acknowledge this: in the ashes of a failed utopia, he dared to imagine a functional republic.

Ziaur Rahman was never an ideologue. He was a strategist with the instincts of a field commander and the eyes of a political realist. In a society where faith ran deep, he understood that the state could not afford to speak a foreign moral language.

But he also knew that sanctifying the state could lead to suffocation. So he walked a tightrope–invoking Islam without empowering its clerics, wrapping the state in symbolic faith while keeping governance functionally secular. It wasn’t purity, but it was balance.

A man of global vision

While his domestic legacy remains polarizing, Zia’s international vision is one of the few points on which even his critics concede ground. He initiated the idea that would become SAARC–South Asia’s only collective diplomatic platform.

He restored Bangladesh’s voice in the global arena with a foreign policy that was multipolar, measured, and deeply tactical.

He normalized relations with China, recalibrated the friendship with India, and deepened strategic ties with the United States. At the same time, he reoriented Bangladesh toward the Muslim world as an economic and diplomatic recalibration.

Labor migration, oil-linked partnerships, remittance flows–all of these lifelines began under his watch. His most symbolic achievement: securing Bangladesh a seat at the UN Security Council. A war-scarred, famine-haunted republic was no longer begging for relevance–it was asserting it.

Zia’s presidency, however, was anything but stable. Coups, conspiracies, and mutinies made his years in office feel less like governance and more like survival in slow motion.

He governed under siege, ruled with caution, and died, ultimately, in the chaos he had once tried to contain. As Machiavelli warned, power protects–but it also isolates.

His assassination in 1981 was a break in national continuity. For a republic just learning how to stand, it was a fall back into limbo. What came next–civilian rule, military interregnums, democratic stumbles–has often played out as either homage to or revolt against the Zia framework.

Today, Ziaur Rahman is less a political figure than a national Rorschach test. Is he the architect of Islamization or a secular tactician in religious garb? A military usurper or a reluctant statesman? A nation-builder or a power consolidator?

The truth is: he was all of them, and none of them.

Zia resists neat biography because the country he shaped remains unfinished. As Paul Ricoeur once observed, “To be forgotten is to die twice.” Four decades after his death, Zia has not faded.

He remains fiercely debated, continuously invoked, endlessly contested. That alone is testament to his enduring hold on the national imagination.

As Bangladesh now faces new fractures–climate peril, democratic fragility, geopolitical recalibrations–perhaps it is time to revisit Zia not as a totem of partisan nostalgia, but as a study in post-conflict statecraft.

His life was a model. A model forged in crisis, tempered by contradiction, and aimed not at perfection, but at functionality.

To remember Ziaur Rahman is not to sanctify him. It is to wrestle with the dilemmas of leadership in a fragile republic. And in that wrestling, perhaps, to recover a vocabulary bold enough to face what comes next.

—

H. M. Nazmul Alam is an Academic, Journalist, and Political Analyst based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. He can be reached at [email protected]