Teen Goyenda: The paperbacks that shaped my wanderlust soul

Before I ever broke free of the schoolyard, I was still locked into a world of plastic lunch boxes and stiff benches.

Childhood lit up my face. Outside school, life was fast, noisy, and thrilling: cartoons that didn’t make sense, footballs flying across dusty fields, birds that didn’t care where they were going, trees that seemed to know more than they let on.

Even the zoo was strange and wonderful. The Padma River felt like it belonged to some other planet. And then came something even more powerful than all of that—books.

Not schoolbooks. Not the heavy, joyless ones with assignments and red marks. The storybooks. The kind that opened doors.

The first ones I remember were from Thakurmar Jhuli–fairy tales with names like Sonar Pakhi and Dalim Kumar’s Horse. I didn’t just read them–I lived inside them. They made reading feel like rebellion.

At home, we used to have the Daily Ittefaq. And there, always on Page 3 in a little corner, was something just for me: Tarzan. The name next to it–Edgar Rice Burroughs–meant nothing to me then. Just a foreign tag. I didn’t know yet that he was the man who made Tarzan real.

Then one day, during a boring class, someone leaned in with a whisper that would change everything. “You talk big about Tarzan after flipping through a few comics? Want the real stuff? Read the books.”

Tarzan had books?

I had no idea where to find them. But this kid–his name’s gone from my memory, but his words stayed–took me to a shop near Kazla Mor. It didn’t sell candy or pens. It sold paperbacks. Tightly packed, a little worn, printed on cheap paper.

And behind the counter: a new language. Rental. One taka a day. On the back of every book was a red-and-yellow butterfly. And under it, a name: Sheba.

Sheba was Dhaka’s own publishing house. It looked like entertainment, but it felt like something deeper–a quiet kind of rebellion. Tarzan was there. I rented one book. Then another. Then every single one they had. I read like I was possessed.

That’s when I started living a double life. School Books on the desk. Sheba thrillers hidden underneath.

But eventually, I wanted to own them, not just borrow. I pulled my mother to Shaheb Bazar, to a shop called Books Pavilion. I asked for Tarzan.

“Out of print,” the man behind the counter said. But then he handed me something else. A thick Sheba book. Too big. Too strange. He smiled like he knew something I didn’t.

“You’ll like this,” he said. “It’s made for kids like you.”

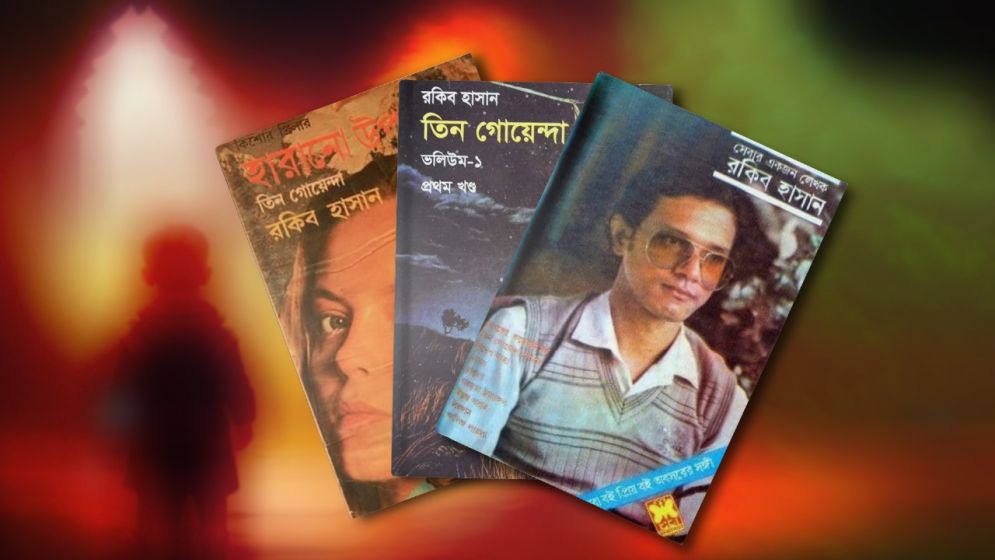

Teen Goyenda, Volume 3. By Rakib Hasan.

The cover was chaos in the best way–coconut trees, gold coins, a golden-haired girl, a wild man, a yellow dog. Six stories packed into one book. “One purchase, six adventures,” the shopkeeper said.

I held it like a treasure.

-683dbd49f279d.png)

Door to a new world

That night, I couldn’t sleep. The Sheba butterfly had taken flight again–and now I had six reasons not to come back down.

I flipped through the pages slowly, like I was holding something sacred. The first story: Harano Timi. It opened with a line that didn’t try to impress, just transported: “Look, Hui Jhe, a fountain is visible!” A whale, breaching. Saltwater, not mythology. But it was enough. I was in.

From there, I fell headfirst into the world of Teen Goyenda. I tore through Harano Timi, Mukto Shikari , Mrittu Khoni, Kakatua Rahasya, Chhuti, Bhuter Hashi. Every story was a new place, and each one taught me something: geography through the plot, culture through dialogue, psychology in disguise.

Soon I wasn’t just reading Teen Goyenda—I was part of them. Kishor Pasha, the smart, thoughtful leader who felt a little like me. Musa Aman, strong and instinctive. Robin Milford, cold, sharp, and precise. Sometimes Jeena Parker or Rafian would show up too–surprise guests who brought even greater joy.

“Obsessed” doesn’t cut it. I tracked down every book I could. Some I found. Others seemed to vanish into thin air. But that only made the stories more real. Names like Harry Price, Director David Christopher, and Mr. Whispers were etched into memory.

The covers were their own language. Musa’s fierce stare on one side, Robin’s hair catching light on the other, and always, somewhere off-center, Kishor–slightly hidden, like he could be anyone. Like he could be me.

Then came Kongkal Dwip and with it, Papalo Harcus, a Greek boy diving for gold off the Aegean coast. He made my landlocked childhood feel like part of something bigger. Years later, standing in a port in Athens, I found myself watching curly-haired boys walk by, half-expecting to find him.

In Bavaria, I waited for someone to say “Hoke” instead of “Okay,” just to prove Boris and Rover were real. In the Caribbean, strapped into diving gear, I didn’t think about my instructor. I thought of Musa Aman, calm under pressure, cutting through water like it was second nature.

Even a hammock in a Brazilian friend’s backyard could send me back–to the first time I read the word “hammock,” somewhere in a jungle scene from Teen Goyenda. And when Juan Vidal panicked at the sound of howler monkeys in Yucatán, I stayed calm.

“They’re harmless,” I told him. “Just loud.”

I didn’t learn that from life. I learned it from a paperback.

-683dbd78eb1a2.png)

My treasure trove

Back home, the first 88 volumes of Teen Goyenda still sit on a shelf. I treat them like heirlooms. Neem leaves between the pages. Dust wiped away like a ritual. Titles like Dakkhiner Dwip, Mummy, Ghorir Golmaal, Chintai–each one a shortcut back to teenage obsession.

I met my first kookaburra not on a birdwatching trip, but in Bhuter Hashi–a detail in a comic horror story featuring a villain named Dungman. Years later, standing in Australia with a cricket bat branded “Kookaburra” and hearing the real bird’s eerie laugh, I realized the story had followed me.

When Icelandic friends ask how I understand their naming traditions, I usually shrug. The truth is, I learned it from Dhusor Meru. In Mexico, looking up at the church Hernán Cortés built on top of a pyramid in Cholula, I didn’t think of colonial history–I thought of a horse’s broken sword, from a long-forgotten paperback.

In Africa, the savannah looked familiar. I remembered poachers–haunting figures in khaki, always lurking. Then two lions appeared, blood on their faces, dragging their kill through tall grass. It felt like a scene from a Teen Goyenda cover. But the true relic was a name: Dr. Louis Leakey. I’d read it once in passing, and it never left.

But over time, something shifted. Cricket stats pushed out call numbers. New Teen Goyenda volumes started feeling rushed, less precise. I drifted. And then, I doubled back– to reinhabit the early volumes, the ones that felt fully alive.

Re-reading them became a quiet return, like revisiting a first love with the benefit of time.

Somewhere along the way, I realized I’d internalized these characters. I approached puzzles like Robin, cared about animals like Musa, and thought in long pauses like Kishor. And always, I carried a Bangladeshi imagination into every fantasy–proof that these stories didn’t just entertain, they shaped identity.

The books gave me habits. After Bhuture Surongo and Dighir Dano, I couldn’t shake my obsession with lake monsters and sea serpents. I scanned the skies for UFOs after reading Mahakash Theke Agontuk. The creature from Bhoyal Giri still lingers whenever I walk through unfamiliar woods.

At Playa Girón in Cuba, I learned the town was named for a 17th-century pirate. I half-expected Louis Decheneaux to appear at the dock–or Omar Sharif, the desert stallion, to emerge from the trees.

Other names surfaced, too. Victor Simon, the disabled detective with his Vietnamese cook, introduced me to global stories long before school did. Toka, a stowaway with a sense of humor, was my first pirate. And Doyle, the wire-haired terrier, deserved far more than the few stories he got.

I wanted him in every book–to bark sense into the grown-ups who never seemed to understand.

-683dbdb930b37.jpeg)

A portal to myself

Some covers held me as tightly as the stories inside. I’d flip through them over and over–Chhuti, Mahabipad, Indrajal, Roktochokkho–drawn to the grainy artwork. These images were entry points. Each one promised a new world–full of risk, shadow, and somehow, familiarity.

The supporting characters felt like extended family. Rashed Uncle. Mary Aunty. Mr. Parker. Kumalo. The strange priest in Roktochokkho. Even Hanson, the quiet chauffeur with his quiet secrets. They weren’t background–they were part of the fabric.

Then came a turning point. A new title appeared: Dhakay Teen Goyenda—Teen Goyenda in Dhaka. Just reading the name was a jolt. Rakib Hasan had done what no one expected. He brought them home.

No more California coastlines. Now they were chasing criminals through the lanes of Dhaka, crossing our rivers, facing our ghosts.

With every story, I wasn’t just traveling–I was collecting. Odd, brilliant facts tucked into crime fiction: the illegal wildlife trade (Poacher), basketball tournaments that felt like war zones (Khelay Nesha), smuggled comic books (Obak Kando), golf balls sold on black markets (Banorer Mukhosh), idol traffickers (Murtir Hunkar), butterfly farms in danger.

They were pieces of a larger education–stranger and more honest than school ever allowed.

Regret has its own shape. For me, it’s a missing book–one where a fake Kishor takes the stage. I lent it to a classmate in seventh grade. He never returned it. I remember the cover. I remember the letdown.

But not all memories are about loss. Some are recoveries. Like the time I tracked down Warning Bell, the one with the boy whose voice sounded just like Kishor’s. I got that copy back after what felt like a small sting operation.

Even now, these books continue to teach me.--how to observe, how to stay curious. And yes, I still believe–irrationally, maybe–that one day I’ll stand on a coral island in southern Polynesia, feet in a blue lagoon, watching a sunset too bright to photograph.

That dream started with Teen Goyenda. The belief that more was possible–that wonder was allowed. For opening up those doors, for urging me to look deeper, to go farther, the debt I owe–to the books, and to the man behind them–only grows.

Rakib Hasan, the writer who created it all, is now seriously ill. Kidney failure. Dialysis. The medical facts are easy to list. The emotional ones are not. A man who spent his life giving kids courage now faces a different kind of struggle, one that plays out slowly, quietly, day by day.

If you ever read Teen Goyenda, if you ever believed in invisible codes or lions that roared from rented paperbacks–maybe you owe him something too.

Even if it’s just a silent thank-you.

—

Tareq Onu is a wanderlust

(Translated from Bangla by Faisal Mahmud)