How Past Lives uses silence and space to speak to my soul

The first time I came across Past Lives–director Celine Song’s quietly luminous debut–I wasn’t in a hushed arthouse theater or scrolling through awards-season recommendations.

I was in a cavernous mall in Bangkok, watching an animated film I can no longer name.

It was Eid-ul-Azha, 2023, and my family–my wife, Nita, and our daughters, Liyana and Ayana–went to Thailand for what was meant to be our first Eid holiday abroad together.

The trip began with the usual anticipation–customs lines, tuk-tuks, buffet breakfasts, bowls of Tom Yum soup–but unraveled midway when Ayana came down with a high, unrelenting fever. She was barely three at the time.

What followed was a rushed midnight visit to Bangkok General Hospital, hours of worry, and the slow recalibration of what counts as a “memorable” family trip.

Before that turn, though, Liyana and I had sneaked away to MBK Center, the sprawling shopping mall that, like much of Bangkok, feels suspended between eras. We went to a movie theater and she had ice cream; I ordered mango sticky rice that was, frankly, sublime.

The movie didn’t matter–it was filler, a placeholder in time–but during the intermission, the lights dimmed, and a trailer played: soft piano notes, sun-drenched streets, a woman on the cusp of choosing between two men and two countries.

I didn’t know then that Past Lives had already premiered to quiet awe at Sundance and would soon become A24’s critical darling, a meditation on longing and the gravitational pull of the lives we don’t lead.

I just knew that I was watching something I wanted to remember. And then, predictably, I forgot.

Next encounter with the film

Life resumed. Work deadlines crept in. I traveled to the U.S. as part of the Jefferson Fellowship, a program that compressed continents into five weeks: Istanbul, San Francisco, Honolulu, Tokyo, Seoul.

On a long-haul flight from Istanbul to San Francisco, scrolling through Turkish Airlines’ vast but inconsistent entertainment catalog, there it was again–Past Lives, nestled between blockbusters and Turkish dramas. I hovered. I passed.

Maybe the timing wasn’t right. Or maybe it’s truer to say that certain stories ask to be received, not merely consumed.

It wasn’t until the return leg–Seoul to Singapore, somewhere over the East China Sea–that I was probably ready.

I’d spent the past month watching landscapes shift outside plane, train and bus windows, standing at crosswalks in foreign cities that reminded me of home, or didn’t.

There’s a particular type of solitude that comes with traveling across time zones: you begin to measure life in layovers, in departures, in a suitcase’s slow accumulation of receipts and memories you won’t catalog.

I pressed play.

Past Lives is a film of silences. It tells the story of two childhood friends in Seoul who reunite in New York decades later. It is not a love triangle in the traditional sense; it’s a ghost story, haunted by the people we used to be.

Song, herself a Korean-Canadian playwright-turned-filmmaker, renders these moments with an almost unbearable restraint.

The ache is not in what’s said, but in what hovers just outside the frame.

Watching it from a window seat, midair and in transit, the film hit with disarming clarity. The bittersweet reunion, the impossibility of fully bridging two identities, two homes, two selves–these were not just narrative devices.

They were, in that moment, autobiographical truths.

The film does not rely on dramatic crescendos or cinematic spectacle. Instead, it offers space–an unusual commodity in the overstimulated world of modern storytelling.

It unfolds in silences, in looks held a second too long, in the subtle choreography of two people walking side by side and never quite touching.

Usage of silence, restraints

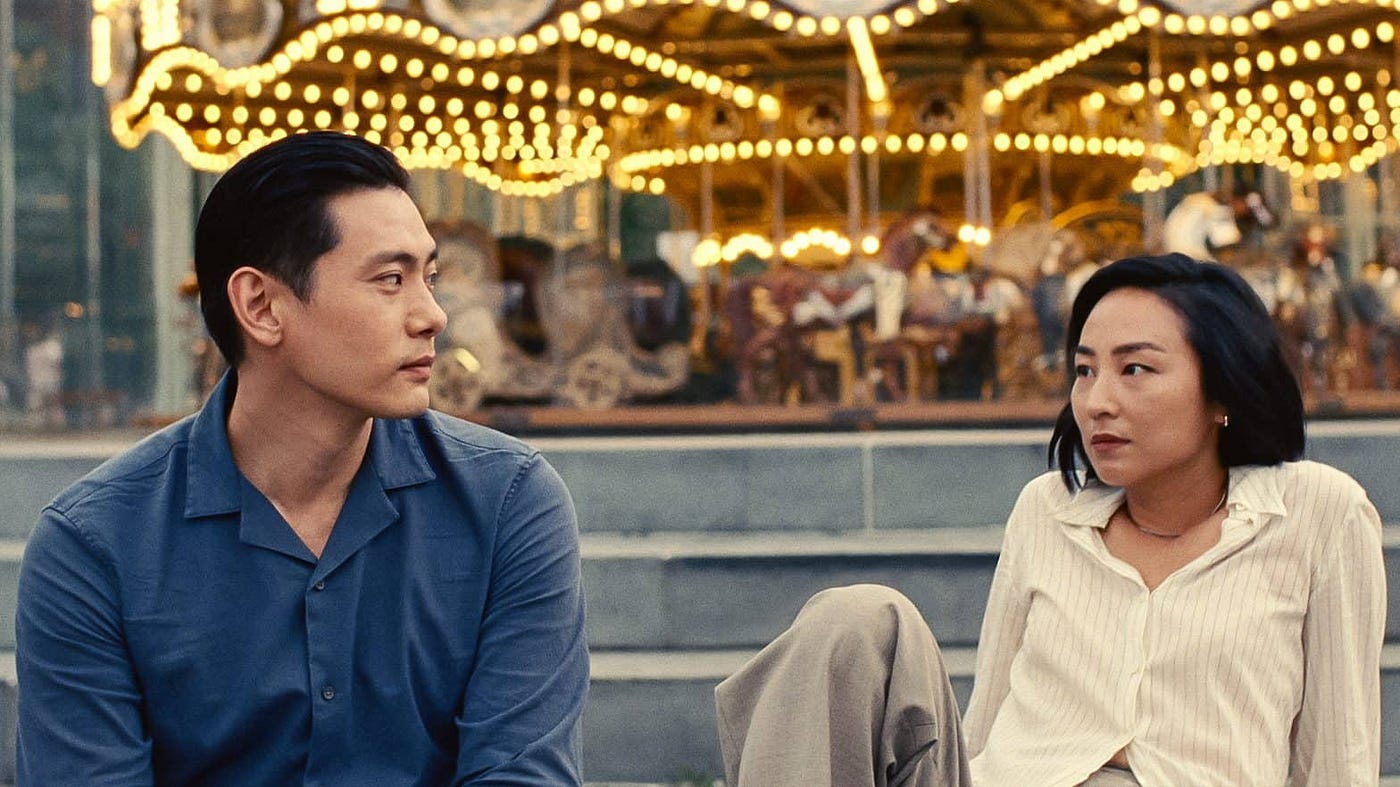

The story, inspired in part by Song’s own life, traces the lifelong pull between Nora, played with amazing restraint by Greta Lee, and her childhood friend Hae Sung (Teo Yoo), whom she leaves behind in Seoul when her family immigrates to Canada.

They reconnect briefly online as young adults, and then again, improbably, in person–twenty-four years after their last face-to-face moment, this time in New York, with Nora now married to Arthur (John Magaro), a quiet, observant writer who senses that some absences take up more space than presence ever could.

Much has been said about the Korean concept of inyeon–the invisible thread that binds people across lifetimes–which Song threads through the film as a kind of metaphysical echo.

But what struck me most, watching it midair between continents, was how physical the film's emotional grammar is: the exacting distance between bodies in frame, the slow orbit of two people circling an unresolved past.

You feel the pull and push of history–not history writ large, but the quiet, deeply personal kind that accrues through ‘almosts’ and ‘what-ifs’.

There’s a scene near the end–almost unbearably still–where Nora and Hae Sung sit on a park bench in the blue-gray dusk of Manhattan, speaking gently, but mostly not speaking at all.

In traditional movie grammar, that could have been the scene of climax or confession. But in Past Lives it’s something rarer: an encounter that holds both closure and endless openness, where time seems to stretch and fold back onto itself.

In that moment, and in many others, Past Lives achieves something almost ineffable. It creates a cinematic field around its characters, a kind of emotional gravity. Not unlike the sensation of flying–quiet, lonely, introspective.

You are moving forward, and yet you are not entirely sure what you’re moving away from.

By the time the credits rolled, I felt like I was inside something: a stillness, a reckoning, a story so acutely attuned to the spaces between people that it left me altered. Subtly. Indelibly.

It is rare for a film to say so much with so little. Rarer still for it to echo afterward–in the rhythm of how you remember your own life.

Past Lives moved me. It became a part of the core architecture of my memory, something lodged just beneath the surface, where other unfinished stories reside.

—

Faisal Mahmud is the Minister (Press) of Bangladesh HIgh Commission in New Delhi