Why the movie ‘Traitor’ stands out as a counterpoint to Hollywood's Islamophobic narratives

In the early 2000s, a letter in the "Letters to the Editor" section of the Masud Rana paperback series caught my attention, and it stuck with me for years.

Unlike the usual fan mail, which either lauded or criticized the storylines of previous installments, this letter posed a direct question to the series' author, Kazi Anwar Hossain.

The reader asked why Israel was always portrayed as the sole villain in the recent Masud Rana books. Hossain’s response was simple: Bangladesh had diplomatic relations with nearly every country except Israel, so, in the world of his espionage thriller, Israel had to be the lone antagonist.

As a high school student at the time, I didn't fully grasp the implications of his answer, but it gave me something to think about. That exchange illuminated a central truth I had never considered before: in fiction, the choice of enemy matters.

The "villain" in a story isn't just a narrative device–it’s a lens through which cultures, political stances, and national identities are shaped. This is not just a matter of storytelling rather it’s also about influence.

What we consume in popular culture molds our perceptions in ways that are often more potent than the news, especially when the facts themselves are murky or difficult to process.

This reality is nowhere more evident than in Hollywood. As Noam Chomsky has noted, Hollywood is perhaps the most powerful media force in shaping global consciousness. And over the past several decades, Hollywood has made a deliberate choice about its "preferred enemies."

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the "evil empire" of the Russians lost its grip on the American imagination. In its place, the Muslim world emerged–specifically, Muslim terrorists–who quickly filled the void as the new villains in the global narrative.

This transition wasn’t just a byproduct of changing geopolitical realities. Hollywood’s portrayal of Muslim characters shifted dramatically after 9/11, with terrorists–usually bearded, turbaned men–becoming the archetype of the "public enemy."

The cinematic trend became so ubiquitous that it went beyond American audiences, influencing how the rest of the world viewed Muslims, too. From Europe to the Middle East, the image of the "Muslim terrorist" was cemented as the ultimate threat to peace and security.

Against the tide

But amid the barrage of films reinforcing this one-dimensional portrayal of Muslims, one movie stood out–not exactly for its plot, but for its rare and nuanced depiction of a Muslim character.

Traitor (2008), a film that slipped under many people's radar, offered a more complex view of a Muslim protagonist caught in the crosshairs of global politics. The film didn’t merely use the character as a foil for an easy narrative of good versus evil.

Instead, it presented him as a multifaceted individual, trapped in a web of competing interests, which is a portrayal almost entirely absent from mainstream Hollywood at the time.

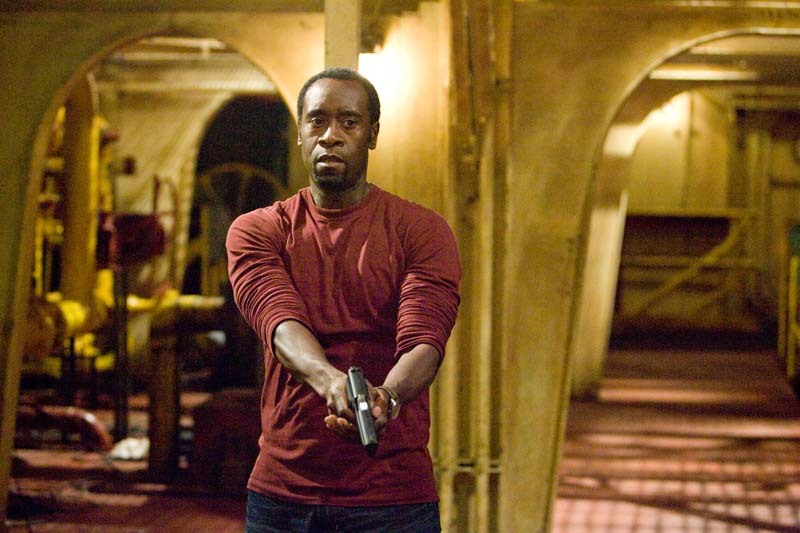

The storyline follows Samir Horn, portrayed by Don Cheadle, a man with no fixed identity. On the surface, Horn appears to be just another American caught in the murky world of international terrorism.

He spends his time moving between Middle Eastern terrorist cells, selling detonators, and forming relationships with shadowy figures, all while maintaining a precarious double life. But soon, we learn that Horn, a devout Muslim, is not what he initially seems.

He isn’t just a pawn in the game of international espionage–he’s part of the system, yet outside it, as well. When asked if he is a devout Muslim, he calmly replies, “I think the word devout is inherent with the word Muslim.”

It’s a line that encapsulates the complex nature of his character: a man torn between his faith and the political realities he must navigate.

The movie takes a sharp turn when Samir, caught in a business meeting in Yemen with an old friend linked to a terrorist group, is arrested by the FBI. It’s in a Yemeni prison that Horn encounters two FBI agents, Roy Clayton (Guy Pearce) and Max Archer (Neal McDonough), who will later become his relentless pursuers as he’s thrust deeper into the world of terror.

As the plot unravels, we’re forced to question the moral boundaries that define "good" and "evil" in the post-9/11 world.

What makes Traitor stand out is its unflinching portrayal of the complexities that define both sides of the war on terror. Horn, while working with a terrorist organization, remains conflicted.

The narrative asks us, and the characters on screen, uncomfortable questions about the similarities between the actions of U.S. intelligence agencies and those of the terrorists they’re trying to defeat. The film doesn’t offer clear answers; instead, it forces us to confront the grey areas of morality and justice.

The climax of Traitor is a harrowing sequence that speaks volumes about the film's themes. A terrorist cell, with Samir at its center, plans a synchronized bombing campaign on Greyhound buses bound for fifty states in the U.S.

The twist, however, is that Samir orchestrates the attack in such a way that all the bombers end up on the same bus. When the moment of truth arrives, one by one, each of the suicide bombers stands, screams “Allah-u-akbar!” and pushes the button.

But by the time the final bomber realizes the fatal flaw in the plan, it’s too late. The bus explodes in a devastating moment of unintended self-destruction.

The uniqueness of the movie

That particular scene is a metaphor for the larger narrative at play: the seemingly clear-cut divides between good and evil, enemy and ally, are often illusions.

In the world of espionage, terrorism, and counterterrorism, the line between the two can blur in ways that leave us questioning who the true "villains" really are. The terrorists in Traitor aren’t just faceless enemies; they are individuals, struggling with the same moral dilemmas as their U.S. counterparts.

And that, perhaps, is the film’s most unsettling revelation: in the end, the real enemy is not a group of people, but the system itself, which forces its agents–on both sides of the conflict–to play a game where no one truly wins.

Precisely because of that, Traitor stands apart from the glut of post-9/11 thriller because of its nuanced portrayal of the complex forces at play in the global war on terror.

Unlike the standard Hollywood formula, which often simplifies the enemy into a monolithic caricature of evil, this film dares to show a more complex and, at times, uncomfortable truth.

Here, we are granted a rare glimpse into the lives of religiously motivated terrorists–individuals driven by a hatred so profound that they are willing to sacrifice their own lives to kill “infidels.”

But at the same time Samir’s unwavering commitment to his faith and his belief that Islam, at its core, is about protecting life—not destroying it.

So, the film’s true ambition is not just to explore the mechanics of terrorism or espionage. Rather, it forces the audience to confront a critical question: Can good and evil both emerge from the same source–religion–and what does that say about how we define morality?

Traitor made a broader statement about personal interpretation–how religious doctrine can be twisted to justify violence, just as it can be used to promote peace.

What’s also most refreshing about Traitor is its refusal to vilify the whole for the actions of the few. Hollywood’s typical tendency is to paint entire cultures or religions with a broad brush, portraying an entire group of people as threats based on the actions of extremists.

This movie resists that temptation, showing that bad apples don’t necessarily spoil the whole barrel. In doing so, it complicates the narrative we’ve come to accept, offering an alternative perspective that challenges viewers to think more critically about the world–and the people–around them.

---

Faisal Mahmud is the Minister (Press) of Bangladesh High Commission in New Delhi