Kilimanjaro: The mountain that sang me upward…

It always takes me time to readjust to the plains after the mountains. This return was no different. Even after the descent, the spell of Kilimanjaro–its forests, its vast slopes–clung to me.

Kilimanjaro was my first encounter with Africa’s mountainous grandeur, and its immensity left me awestruck. Yet, if I am honest, my heart still tilts toward the Himalayas. So rather than draw comparisons, I will linger on what made this climb singular.

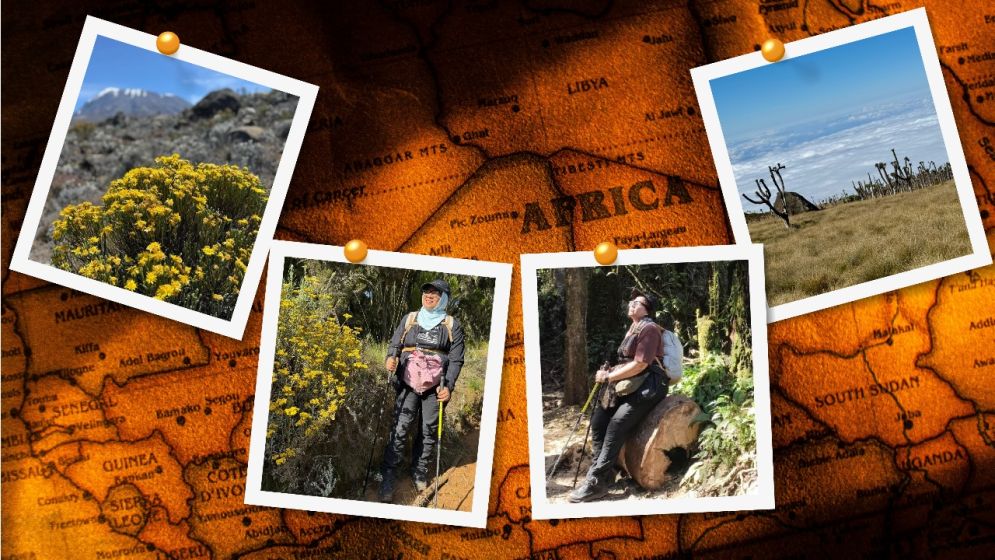

Our African journey began with a safari across Kenya’s Maasai Mara, a sweep of golden grasslands alive with lions, elephants, cheetah, wildebeest and more. Four days later, the safari gave way to the real reason we had crossed continents: the ascent of Kilimanjaro.

The transition was less seamless than we had hoped. A tedious border crossing between Kenya and Tanzania, followed by a late-night arrival in Moshi–a small, bustling town that serves as the last outpost for climbers–set the stage.

At our hotel, we finally met our formidable support team: a caravan of guides and porters, led by a gregarious man named Simone, whose booming laugh seemed to dissolve our fatigue.

The following morning, after the briefest of respites, we were back on the road. Ahead lay the Marangu Gate—the starting point of the trail to Africa’s highest peak.

Box lunches in hand, forms signed, and photos snapped, we watched the porters–already balancing and bundling our luggage with practiced ease–set off ahead of us. Within minutes of walking, we were swallowed by a forest.

It was dense, evergreen, almost primeval. Ancient trunks wore coats of moss. Ferns unfurled from every corner. For nature lovers, it was nothing short of enchantment. I even found myself daydreaming about orchids clinging to these damp giants.

The trail itself was forgiving, reminiscent of the path from Bamboo to Langtang Valley in Nepal Himalayas. Towering trees forced us to tilt our necks skyward in search of birds. Instead, two long, white-tailed monkeys appeared, balancing on high branches–creatures that looked more feline than simian.

Startled by our presence, they darted deeper into the canopy. Our guide pointed out a small animal tucked inside a hollow trunk, rabbit-sized but with the face of a koala. Its name escapes me, though its strangeness lingers.

Halfway up, a wooden bridge appeared, perfect for photographs. A rest stop soon followed: benches, a washroom, a designated picnic spot. The kind of thoughtful pause that softened the climb.

Still, fatigue crept in. It was the first day, after all. A strained muscle from an overzealous stride reminded me that mountains don’t tolerate impatience. Steadier steps carried me the rest of the way until the forest opened into Mandara Hut–our first day stoppage.

It was a settlement nestled in green, with cottages scattered along the slope. Cold air seeped in quickly, and by evening I instinctively drifted toward the dining area, expecting the familiar warmth of a fire.

But here, no flames were allowed. A catastrophic blaze three years ago had scarred the land, turning fire into a forbidden luxury.

Instead, we bundled up, warm socks doubling as mittens, and surrendered to the chill. Then, stepping outside, I looked up.

The night sky revealed itself in its raw, untouched splendor. The Milky Way stretched wide, shimmering with a density of stars no city dweller can truly fathom.

At that moment, the cold no longer mattered. I could only whisper gratitude. Alhamdulillah.

Exhaustion and cold sent me to sleep quickly, but the mountain has its own way of waking you. At 4:30 a.m., I stepped outside, uneasy in the pitch-black forest.

The washroom was across the clearing, and the only light came from the stars, so bright, so unearthly, that they seemed to illuminate the path more faithfully than any lantern could.

By morning, a plastic basin of “warm” water awaited us outside the hut, though the chill had claimed it long before I could summon the courage to leave my sleeping bag. Still, the ritual of washing in that biting air felt bracing.

Breakfast was set neatly on long tables, a small comfort against the thin mountain cold. In daylight, the forest revealed its quieter companions: birds flitting between branches and the same white-tailed monkeys, perched high, watching us with cautious eyes.

There was little time to linger. The mountain does not indulge dawdlers, and we had to leave before I could take in more of Mandara’s quiet beauty.

From forest to moorland

The second day trek began where the first had ended–under the canopy of forest. But soon the trees thinned, and the trail opened into scrubland. We paused among junipers and thuja bushes for a “sneakers break,” snapping a few quick photos.

Privacy was scarce in the open fields that followed, so everyone ducked behind bushes when necessary–only to discover, moments later, a tin-shed toilet standing plainly beside the trail.

The monotony of the open field was numbing. The sun pressed down, my eyelids grew heavy, and the restless night caught up with me. Step by step, I slowed until I was the last one on the path.

The guide relieved me of my backpack, but even then, my legs resisted. At one point, I walked with eyes completely shut, one hand clinging to the corner of the guide’s pack. Oddly, it worked. It felt almost luxurious, as if my body were moving while my mind drifted in sleep. Ten minutes later, I was restored.

By the time we reached Horombo Hut, the reward was beyond expectation. The approach burst into color–yellow and white flowers, thorny cacti, and slopes rolling down into valleys swallowed by clouds. From the courtyard, it looked as though the world below had vanished, and we were perched in heaven itself.

Horombo felt like a small victory: solar-powered lights, clean toilets, and sturdy cottages. The late afternoon sun warmed us like a winter day back home. Dinner was hearty, the kind that satisfies both hunger and exhaustion.

Tomorrow promised no rush–an acclimatization day–so I went to sleep ready for rest. That was until Setu’s sharp voice cut through the night, scolding someone who seemed to talk endlessly from our adjacent room, like a radio that wouldn’t turn off. The voice droned on; the mountain gave no silence.

Morning brought its own comfort. A basin of hot water, a relief against the alpine cold. At breakfast, I discovered Kilimanjaro tea–rich, fragrant, unforgettable. I became an instant devotee.

Later, we hiked 400 meters higher to Zebra Rocks, where striped cliffs rose stark against the sky. The mood turned celebratory. Someone played the song “Jamal Kudu,” and soon we were dancing in the thin air, laughing without reason, as though it really were a wedding.

The walk back was pure cinema: wildflowers carpeting the hillside, and across the horizon, Kilimanjaro’s snow crown gleaming like a backdrop in a film. At Horombo, the afternoons were the finest gift–sunlight spilling across the slopes, the world below drowned in clouds.

Some landscapes resist photographs. Horombo was one of them. Its beauty etched itself not on my camera but in memory–untouchable and impossible to forget.

The vastness of alpine dessert

The third morning began with a small ritual: one last chance to send messages and make calls. Beyond this point, the network would vanish for two days–a stretch of silence in a landscape that felt increasingly desolate.

The trail started gently, under a clear, bright sun. Still, the guides reminded us to keep our down jackets close. Their caution made sense soon enough. As the trees and bushes disappeared, the path turned into a barren sweep of volcanic rock and dust.

The Himalayas had taught me about vastness, but this was different. This was desert.

The wind came first–sharp, bone-rattling gusts that cut through layers. Then the sun returned, warm but relentless, pressing on lungs already laboring in thin air. We stopped often, resting in short bursts.

The guides never rushed us, matching our halting rhythm step for step. At one point, Setu tried to lighten the mood, asking a guide if he watched Indian movies. His face lit up instantly: “Kuch Kuch Hota Hai?” he exclaimed, before breaking into a dance step. Even in this barren no-man’s-land, Bollywood had found its echo.

By the time the wind had drained us, a picnic table in the middle of the alpine desert appeared like an oasis–spread with fruit, juice, eggs, pasta. But one seat remained empty. Mala, struggling badly with oxygen, trailed behind. When she finally staggered in, her face was pale, her breathing labored.

Hot tea and juice didn’t help. The guides urged me to go on ahead. I assumed she would be taken back down.

I trudged forward. The sight that unfolded nearly broke me: a looming slope of crumbling rock, as if the mountain itself were daring me to turn back. My heart sank. The guide, reading my despair, offered reassurance. “It only looks steep,” he said. “It’s really just a flat zigzag.” I wanted to believe him. Perhaps I needed to.

By late afternoon, we staggered into Kibo Hut. The cold hit instantly, a cold that bypassed skin and burrowed into bone. My body shook uncontrollably. I felt ill. Then Mala appeared, dragged in by the guides, disheveled but alive.

Her oxygen reading registered at 60 percent. Most of the others had dropped to 70 or 80. Mine, surprisingly, held at 90.

Dinner was served at 6:30, but no one lingered. The plan was clear: sleep fast, wake at 10:30, push for the summit in the dark. But I knew my answer. If I was freezing here, how would I survive the climb at midnight? Besides, the guides had insisted on bringing Mala up against all odds. I trusted they’d drag me down if it came to that.

When the group tried to rally me, I shrugged. Pointing at the red button on my “Mountain Calling” T-shirt, I joked: “Declined.” The decision seemed final when Dr. Hamza checked our gear.

My five upper layers were sufficient, he said, but my pants–thin, doubled–were useless against the mountain cold. Yesterday’s heavier pair, now dust-stained, lay unworn. His verdict: I was not going up. Relief washed over me. Secretly, I began plotting something else: tomorrow, I’d wear a sari at Kibo Hut and pose for photographs.

I must have drifted off quickly, because the next sound I remember was the rustle of others rising at 10:30. Guides checked head torches, boots, layers. One came to my bed and asked gently, “You’re not going, right? Can I borrow your spare batteries? Mine are dead.” I handed over the fresh set I had carried for this very moment.

And then they were gone. Boots crunching, voices fading into the frozen dark. Mala and I stayed behind, cocooned in the silence of Kibo Hut, while the mountain waited for those willing to challenge its summit.

My sudden push for summit

After the others left for the summit, sleep wouldn’t come. The hut was silent, but my mind was restless. I called out to Mala, asking how she was. Her breathing was still labored. I assumed we’d both descend in the morning.

Then came a knock. Dr. Hamza and Simon appeared, checking in. “How are you feeling?” they asked. “Fine,” I replied, perhaps too quickly. Hamza wanted to see what extra clothing I had.

I pulled out my loose Nepali pants–thick cotton, hardly technical gear. “Wear these,” he said, “and add another pair of socks.” Simon rummaged around and produced a fleece from someone else’s kit. He dressed me himself, even tying my shoelaces like a parent fussing over a child on the first day of school.

“Look,” someone explained gently, “there are three summit points. Go as far as you can. You’re fine. You can do this.” And just like that, against my earlier resolve, I was coaxed into joining. My daypack was filled with water, an apple, and juice.

My guide for the climb was a man named King. I told Mala, “I’ll see how far I get. I’ll be back soon.”

Outside, the mountain was black and silent, pierced only by stars. I adjusted my headlamp and began, five layers on top, three below. The cold had lost its bite. Slowly, step by step, we climbed.

Ahead, a necklace of headlamps curved up the slope. They looked deceptively close, but King told me they were an hour away. We rested by a cluster of boulders. From there, I looked down: city lights glittered faintly below, caught in a sea of cloud. For a moment, it was disheartening. Civilization was so near, yet I was straining every muscle to inch further away from it.

The trail was merciless–loose sand and rock that slipped underfoot. I remembered yesterday’s cheerful guide insisting the route was just a flat zigzag. King laughed when I brought it up. “We only say that to keep trekkers moving,” he admitted. Brutal honesty, but refreshing.

I had promised myself not to look up, not to measure the distance by those ahead. I counted steps instead: fifty, then thirty, then twenty before stopping again. After twenty-five switchbacks, I asked how many more there were. “About forty-five,” King replied without hesitation.

So much for encouragement. I abandoned counting altogether.

Exhaustion mounted, and I tried to bargain with myself. I’d go as far as the sunrise, I decided, and then turn back. Soon, a faint reddish glow spread in the eastern sky. What I had mistaken in the night for the sea was nothing more than a vast ocean of clouds.

There was no place to stand, but I stopped anyway. King snapped my picture. I took several myself, trying to freeze the moment before it slipped away.

As dawn broke, I spotted Bobby with her guide on the slope above. For a moment, I thought she had already summited and was returning. The sight lifted me. If she was on her way down, I must be close. I steadied my pace and pressed on.

The “zigzag” path seemed endless. When it finally gave way, it wasn’t to a triumphant summit plateau but to a jumble of massive rocks. There was no trail, only bouldering. My guide urged me on, competing–of all things–with two young Kenyan climbers.

“Go, go, before they reach the top!” he shouted. I handed him my poles and climbed the rocks with my hands, almost enjoying the scramble.

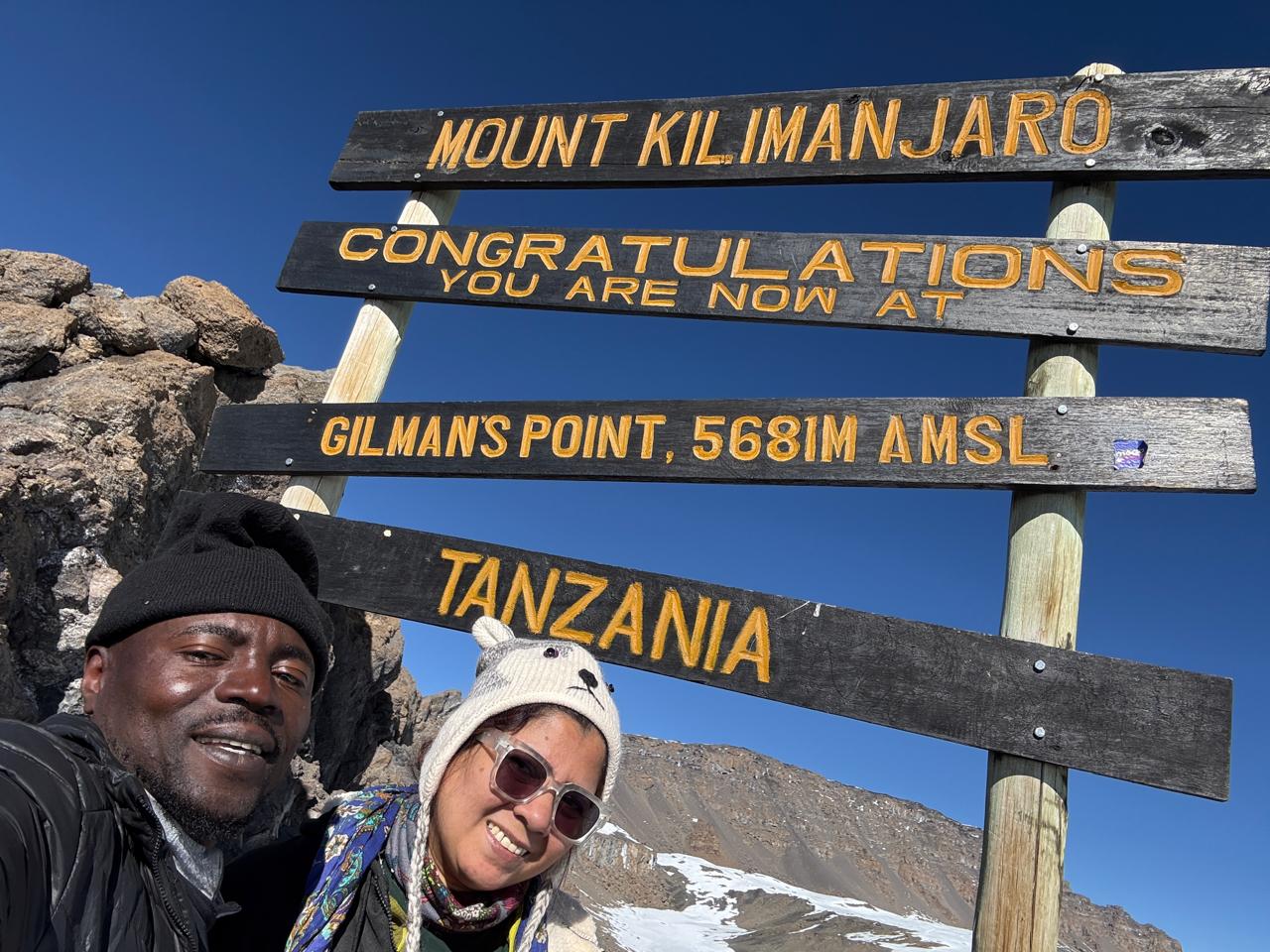

At last, we reached Gilman’s Point. The reality was deflating: a signpost, a patch of ground barely ten feet wide, and another trail branching left toward Stella Point. Exhausted, I sank onto a rock.

From a distance, I could make out my team at Stella, taking photos before heading to Uhuru Peak. I knew if I followed, I’d have no strength for the long return to Horombo. The day’s descent would demand 2,200 meters, more if I went farther.

I made my choice. I stayed. I bit into the apple Simon had tucked into my pack and started down. It was 9:05 a.m.

The descent was swift–gravity an ally now. With rock-climbing instincts guiding me, I dropped quickly, pausing only when I saw Bobby sprawled face-down on a boulder, arms outstretched.

Panic struck–was it altitude sickness? The guide shook his head. She was simply exhausted. I let her rest and moved on.

As the sun climbed higher, the trail turned harsh. My water was gone. Just as fatigue was taking hold, we came across three people seated casually on the rocks. Smiling, they offered me and my guide glasses of juice–an unexpected kindness that felt almost divine.

By 2 p.m., I staggered into Kibo Hut. Simon rushed to greet me, congratulating me with unguarded joy. Only then did it sink in: I had summited. Not Uhuru, but enough to count. Enough for me.

Inside, Mala was still unwell. I began packing immediately, afraid that delaying would only complicate things later. The hut was chaotic–gear scattered, trekkers sprawled. Mala urged me to rest first, but I kept packing. Order was its own comfort.

Soon after, Bobby stumbled back in, pale but smiling. She had summited, too, though she was already talking about descending to Horombo before her condition worsened.

All I could think of was sleep. But Kibo Hut allows no second night; water is too scarce. Lunch was brought to our beds, and by the time we finished, the order was clear: pack up and move on.

By then, Tashmim and Rahi had returned as well. I handed Rahi Setu’s bag. Looking out, I saw Rana Bhai setting up his tripod, capturing a time-lapse of the sunrise. Rahi waved toward us.

At that moment, I thought: we had made it to the highest point of this beautiful continent. Each of us, in our own way.

—