Maverick economist bats for effective “oligarchic management” to achieve meaningful reforms

During the 15-year rule of the Awami League, praise for its development and economic achievements flew free—even in the Western world, which typically values facts over rhetoric.

Many economists were enthusiastic in their support of Sheikh Hasina’s economic and development policies, believing she had paved an “unprecedented” path for progress.

Dr. Rashed Al Mahmud Titumir is one of the few who has long argued that Hasina’s celebrated narrative of development is built on faulty premises and inflated data that don’t hold up under scrutiny.

In television talk shows and newspaper columns, Dr. Titumir, a professor of Economics and former chairman of the Development Studies department of Dhaka University, often came across as a maverick, warning of an impending crisis that seemed far from imminent.

Following Hasina's ousting on August 5, many—including economists— however attribute the country's challenges to her mismanagement of the economy, which resulted in significant corruption, inflation, unemployment, and a decline in purchasing power during her final years.

This situation, now they say, has created a volatile environment, akin to a powder keg waiting for a spark.

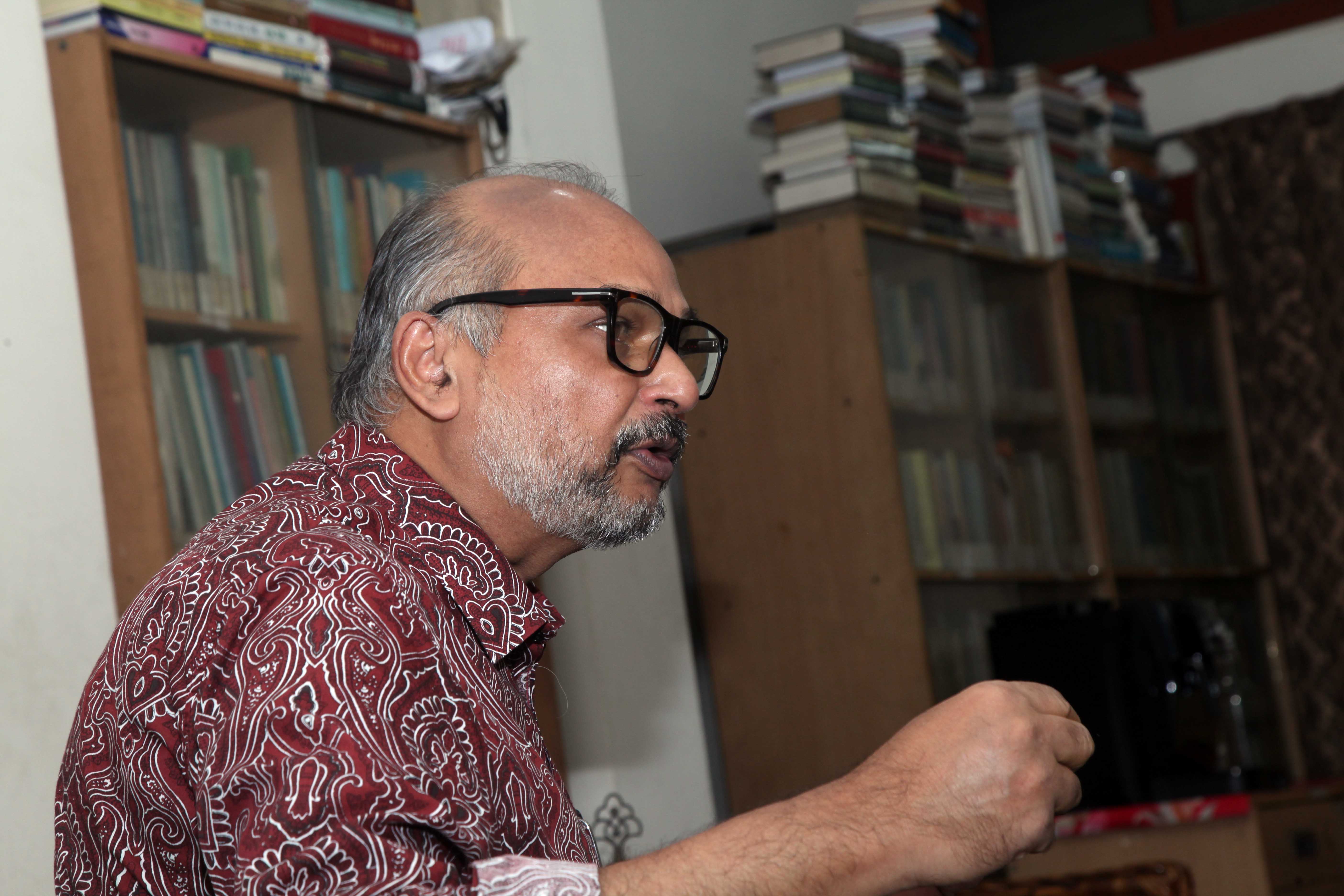

On an October afternoon, Faisal Mahmud, the editor of Bangla Outlook (English) met with Dr. Titumir in his study, and over cups of coffee, discussed the current state of the economy and what the future may hold.

-670d0192af170.jpg)

Here is an excerpt of that interview.

Faisal Mahmud: Before we dive deeper into the economic situation, could you briefly share your perspective on "The Long July Revolution" in Bangladesh?

Dr Rashed Al Mahmud Titumir: I see it as a monsoon tempest marked by one victory and one defeat. The victory is notable because we had a regime devoid of representation and legitimacy, characterized by a collusion between wealth creators and rule-makers. This resulted in an oligarchic, rentier society.

Drawing from the French example of Louis XVI– his survival wasn't due to crony capitalism or neopatrimonialism; it stemmed from a rent-dependent state that supported a resource-driven syndicate. It's important to distinguish this from rent-seeking behavior, where a businessman trades money for power. In Bangladesh, this distinction is often missed, leading to misunderstandings in Western interpretations.

Some statistics illustrate this point. When Sheikh Hasina took office in 2009, defaulted bank loans stood at around 2.24 trillion taka. Now, according to the latest data, that figure has surged to 183 trillion taka, with those loans never repaid. This highlights how certain individuals have profited from the system.

Moreover, when she came to power, our total debt was 23.5 billion dollars. While precise statistics are hard to come by, estimates suggest it's closer to 100 billion dollars now. This indicates that some have benefited from government loans without the expectation of repayment.

This scenario has nurtured oligarchic clientelism, forming connections among politicians, bureaucrats, and businesspeople at all levels, making it challenging for outsiders to penetrate their network. The widespread rent-sharing has led to public anger and unrest. However, this situation isn't comparable to typical spring uprisings or color revolutions; it resembles a monsoon tempest that clears the way for change.

If we were to invoke Shakespeare, it would echo Prospero's world, where characters like Caliban and Miranda find themselves in turmoil. This reflects a victory for the people against a system rooted in illegitimacy and patronage.

On the other hand, there is a defeat as well. The prevalence of false narratives and mis-and-dis-information about Bangladesh’s development over the past decade under Hasina's regime still remains unchallenged to a large extent. While the West often gets blamed for these misconceptions, it’s crucial to acknowledge that this disinformation masks the reality of a democratic deficit.

When media outlets like AFP and AP claim that the government has lifted millions out of poverty, they overlook the ground reality. Since 2009, I’ve been scrutinizing government data, and it’s evident that a revised estimate is necessary. For instance, 10 billion of our exports were recently unaccounted for, raising serious questions about GDP figures.

GDP is calculated using the expenditure approach, which includes consumption and investment, government spending, and net exports. If we examine the import figures, which have not been thoroughly analyzed, along with remittance data, the true picture becomes much less clear.

FM: Ok, now let's discuss the economy. My first question is quite simple: After 15 years in power, the Awami League has developed a close relationship with the business community. How do you anticipate this will evolve in the coming months and years? Do you think there might be any witch hunts aimed at business leaders because of their ties to the Awami League?

RAMT: I’d like to refer back to a French concept, specifically the regime of Robespierre and the Jacobins. In a rentier society like that, tensions inevitably arise, especially in the absence of functional politics or effective institutions, leading to unwarranted situations. The challenge ahead for the interim government is significant, particularly given its unique formation at this critical juncture.

I describe it as unique due to the specific circumstances it faces. The leadership will play a crucial role, as there’s little appetite for simply replacing Hasina’s clientele with others. This situation arises from a social approval process that questions the very foundations of governance.

Many agree that Bangladesh needs a new social contract. In a sense, we’re looking for a second republic, akin to how France moved from its first to fifth republic. The key will be how this political settlement develops, as a public society—meaning one that represents not just the majority but the median population—is essential for progress.

FM: So where do we currently stand? You're addressing what the future may bring and whether business leaders associated with the Awami League will encounter any consequences from this administration or a future one?

RAMT: I wouldn't phrase it that way. My main focus is on the connection between political settlement and economic outcomes. This perspective has been my emphasis since 2009, and I published a book on the subject in Bangla in 2019. While many economists address political economy, I believe these factors are intricately linked and vital for understanding any economy.

Right now, we are facing serious challenges. For example, our debt payments have surged from $23.5 billion in 2009 to $99.6 billion by March 2024. This escalating debt is occurring alongside a decline in foreign reserves and a depreciation of our local currency against international currencies.

Job creation and macroeconomic stability are essential. We need structural reforms and appropriate frameworks. Additionally, credit rating agencies are downgrading us, resulting in stagnant foreign direct investment, which has even seen negative growth.

We’re in a situation where the economy is struggling. The state needs cash, businesses require liquidity, and the general population is also in need of funds. Meanwhile, debt levels for households, firms, and the government are climbing. Real incomes for both businesses and households have not risen, and inflation remains high.

On the government side, despite doubts about the reliability of our data, our tax-to-GDP ratio is one of the lowest globally—just above Afghanistan—with only 11% of the population paying taxes. This creates a fiscal dilemma, compounded by macroeconomic imbalance and real economic challenges.

Utility costs, especially for gas and electricity, are rising, which is crucial for our garment industry that relies on low labor and utility expenses. Additionally, the government has not pursued gas exploration in the Bay of Bengal, leaving us entirely reliant on energy imports. These issues arise from a lack of macroeconomic balance, constrained fiscal capacity, and real economic difficulties.

FM: So, what do you think should be the government’s immediate approach for a real economic reform?

RAMT: We’re currently experiencing an unprecedented period in Bangladesh, marked by a significant rise in people’s expectations. Citizens are increasingly vocal about their desire for reforms, and discussions around civil and political rights are gaining traction, which they have every right to advocate for.

However, the most urgent issue we face is that while wages remain stagnant, prices continue to rise without any indication of decline, a trend that has persisted for several years.

To effectively pursue functional economic reform, my initial approach would be to implement a robust oligarchic management policy. As I pointed out earlier, Bangladesh has developed a rentier society, and we need to find effective strategies to address this issue. It's important to recognize that institutional structures like oligarchy and clientelism must be replaced with alternative arrangements. This isn't just a matter of law and order. If we don't, we risk increasing the number of oligarchs as a result of half-hearted reforms from the 2006-2007 1/11 period. Only by establishing new institutional frameworks can we address the existing oligarchic system and combat runaway inflation.

We should remember that inflationary pressures primarily arise from imported commodities, particularly food and energy. These cannot be sourced by mid-sized companies, highlighting the need for different institutional structures. Innovation is crucial in this context; a new system is essential. Otherwise, we may unfortunately see a resurgence of oligarchy, as history has shown.

FM: One point to consider is that the term "oligarchy" has gained a negative connotation in our perception. However, originally, the word did not carry such a negative implication… I believe…

RAMT: Yes, you're right. When we examine development trends in various countries, we see examples like Japan's zaibatsu and South Korea's chaebol—essentially groups of oligarchs that have played a crucial role in their nations' industrialization and growth. This success stems from their governments disciplining of oligarchic management and bringing order and predictability.

In contrast, Bangladesh operates within an oligarchic framework that resembles a rentier society. To put it simply, these structures function similarly to a Mafia. We must recognize that the negative perception of oligarchy in Bangladesh arises from its failure to foster productive capital development; instead, it has largely focused on rent-seeking behavior. As we all know, and as I've mentioned on several occasions, the Bangladesh model is unsustainable because it lacks an investment-led approach.

FM: Don’t you think this oligarchic management policy might have some drawbacks? For instance, Japan's Liberal Democratic Party has been in power for about 70 years, even in a democratic system. To establish an effective government mechanism like Japan’s, wouldn’t it be essential to focus on two key factors: first, reducing corruption, and second, allowing for a certain level of autocracy?

RAMT: No, that’s a misunderstanding. There’s a flawed narrative suggesting this reflects authoritarian tendencies or order. Authoritarianism existed even during Ayub Khan's era. The development processes in South Korea and Pakistan started simultaneously, so why didn’t they take the same path? We need to examine the nuances in each case. In one instance, there was a functioning and independent private sector, while in the other, the state was attempting to drive production—two very different approaches.

In Bangladesh, for the past 15 years, our economy has been largely consumption-based, as shown by GDP figures, with no reliance on investment. Flawed oligarchic management and rent-distribution have facilitated this and maintained the status quo. This leads me to my second approach for economic reform: shifting from consumption-driven growth to investment-led growth.

FM: There's a common belief that foreign direct investment (FDI) doesn't flow easily without an elected government, whether it's army-backed or a caretaker administration, because potential investors are apprehensive. After all, this government is temporary.

RAMT: To some extent, that's true. However, with Dr. Muhammad Yunus leading the interim government, I believe there's no better ambassador for Bangladesh to the West. Therefore, I don’t expect FDI to dry up during this period.

It's important to recognize that in the past, both domestic investment and FDI have declined due to a lack of confidence. When risks are high, investors are reluctant to commit. International organizations like the United Nations, along with its specialized agencies such as the World Bank, IMF, and ADB, understand this dynamic.

If we can maintain law and order and mitigate risks for foreign investors, we can enhance our FDI prospects. We need to move away from relying solely on loans. Instead of increasing our debt-to-GDP ratio, we should focus on improving our tax-to-GDP and investment-to-GDP ratios, which can be achieved with concerted efforts.

FM: If we examine Asia and broadly divide it into six regions, we find that South Asia is the poorest among them. What accounts for this disparity?

RAMT: The tendency to engage in political arguments rather than meaningful dialogue in this region has left many issues inadequately addressed, including connectivity among states, despite our abundant natural resources. Our "natural heir" mentality, rooted in the British colonial era, leads some to adopt a patronizing stance, saying, "You are my elder brother."

This mindset hinders human development and militarizes our environment in this region and that’s why we are witnessing a consolidation of the global poor, creating a false dichotomy that distracts from challenges.

However, I believe that Bangladesh is uniquely positioned between wheat-consuming states to the west and rice-consuming states to the east, giving us the opportunity to become a positive anomaly in South Asia. We can foster strong relationships with ASEAN countries by highlighting our shared Asian heritage, rooted in historical connections like the monsoon season and the southwest seasonal winds linking us to the West, while the northeast connects us to the East and our rice-based cultivation.

Although ASEAN may question our similarities, they are abundant, particularly in our shared rice civilization that spans from Japan to our region. This perspective can enhance our foreign policy by allowing us to avoid a narrow alignment with the Indo-Pacific narrative or a sole focus on the Belt and Road Initiative. With our western region linked to India, Bangladesh can emphasize its Bengal deltaic civilizational identity and engage with nations that share our unique connections through a practical approach.

FM: In summary, what advice would you give to the interim government for implementing meaningful reforms?

RAMT: First, it's important to note that the interim government is just that—temporary—and political decisions should be handled politically. If we draft reforms, they must be executed by political parties who will ultimately decide their acceptance and the processes involved. Technocrats like us have limitations; we can provide various options, but the actual implementation will rest with politicians. They have at least four potential paths to consider.

The first path involves streamlining the election process, which means addressing necessary reforms for the elections to take place. This includes resolving issues regarding the Election Commission, particularly past allegations of misconduct. To hold elections, we need to rebuild trust in the judiciary, as it has in recent past been perceived as partisan. This is a basic step toward establishing a foundation.

Another approach could focus on various conventions. The U.S. Constitution is often regarded as the gold standard in the liberal world, yet it remains a work in progress. Historical compromises, like those between New Jersey and Connecticut, demonstrate this dynamic evolution. Influential figures such as Alexander Hamilton, John Adams and John Jay wrote a series of 85 essays under a collective pseudonym, Publius in New York’s newspapers, illustrating the need for open debate and discussion prior to any conventions.

The third path involves seeking a mandate for drafting our country's constitution through a constituent assembly. As I have previously stated, what we had was not a genuine constituent assembly, resulting in a state born of conflict that failed to accurately represent its mandate.

The fourth path entails continuing to function while also maintaining both the constituent assembly and the legislature. This process must be political; you cannot establish politics through depoliticization. Citizenship is inherently a political matter, and we must examine its historical contexts. We often engage in debates that lack political grounding, but that should not deter us from discussing important issues. Debate is crucial. Some might assert that communalism is an unquestionable cultural truth, but that doesn't mean we should cease our discussions.

So, our political and economic future depends on establishing a new political framework rooted in delta-based civilization, which requires cultivating a new culture. We are a state shaped by the Ganges, Meghna, and Brahmaputra river basins, embracing diversity through these waterways. It's encouraging to see these discussions taking place in educational instructions. For example, on May 5-6 this year, we held an important seminar at Dhaka University’s Development Studies Association, where I emphasized that the solution lies in a rights-based civilization.

While a delta-based civilization is structurally necessary, we also need a functional approach. Addressing the economic foundations of future crises through the politics of production is crucial; otherwise, one crisis will inevitably lead to another.

FM: Thank you, for your time.

—-