Prominent young IG Advisor rejects future of Pro-India or Pro-Pakistan politics in Bangladesh

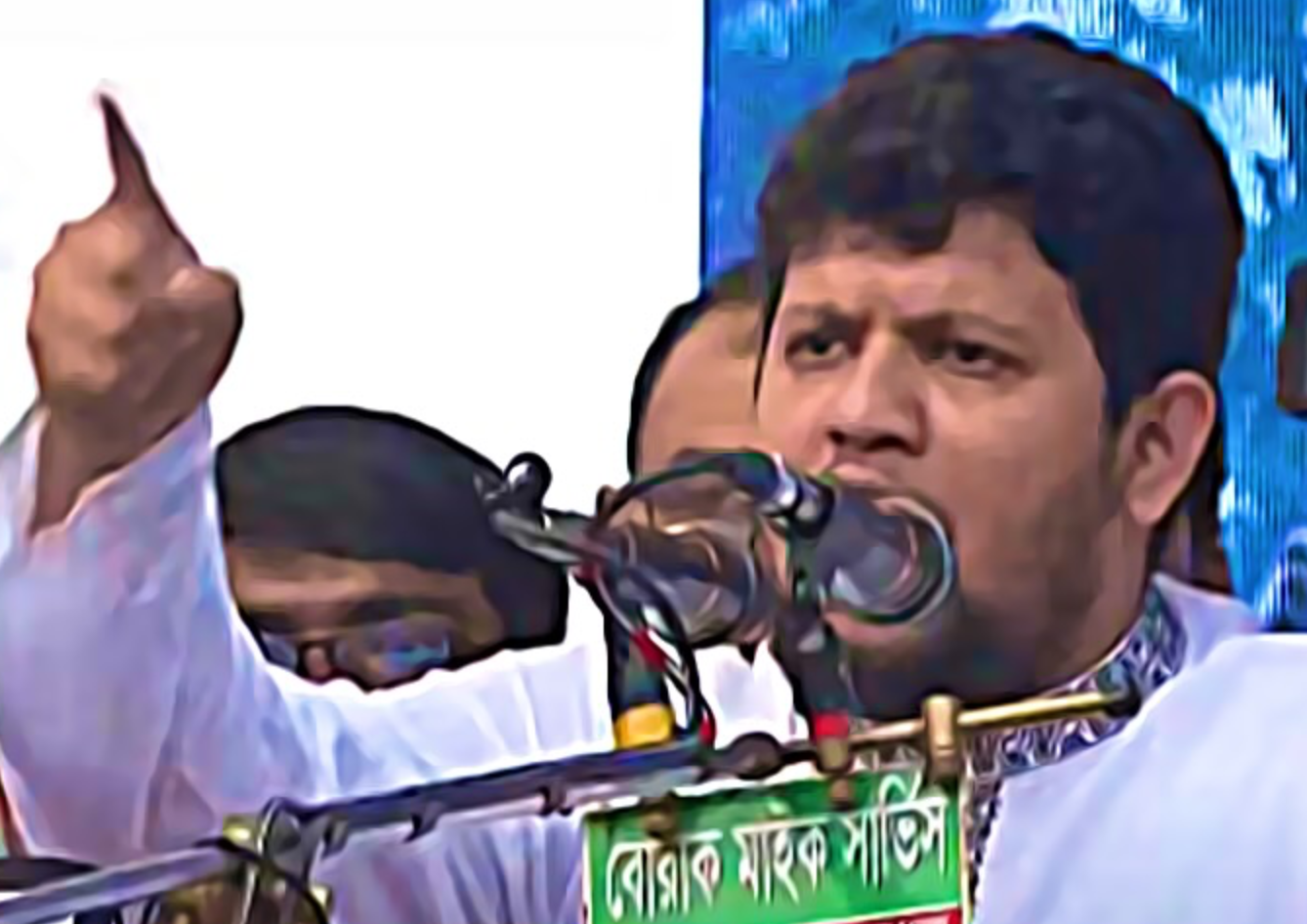

Mahfuj Alam's mysticism and thought process have become some of the most talked-about topics in post-uprising Bangladesh.

A strategist and thinker, Mahfuj was not on anyone's radar during the early days of the tumultuous Long July Uprising.

However, at the height of the uprising, a news portal published an article suggesting there was a “mastermind” working behind the scenes to ensure the uprising would achieve its ultimate goal—overthrowing Sheikh Hasina's fascist regime.

Following the uprising, Mahfuj was frequently introduced in various forums as that “mastermind” — a title he had initially rejected. He believes the collective will and power of the people spontaneously brought down Hasina's dictatorship, and nothing more.

Kolkata-based journalist Arka Deb recently interviewed this charismatic young man and published the conversation on Inscript.me, a portal where Arka serves as the editor-in-chief.

This enlightening interview has been translated into English with the author’s permission and is presented here for the readers of Bangla Outlook (English).

[Disclaimer: When this interview was first published, Mahfuj Alam was still an advisor without a portfolio. Recently, after Nahid Islam resigned from his position as Advisor, Mahfuj was given the charge of the Information Ministry.]

Arka Deb: The Chief Advisor referred to you as the mastermind behind this revolution. Given the circumstances, how do you feel about this? Does this label bring you comfort or discomfort?

Mahfuj Alam: When he first said this, he might have thought that despite the spontaneous nature of the movement, there were underlying triggers. Someone must have been leading, someone must have been guiding. From that perspective, he may have made that statement.

However, the way it has been portrayed, both domestically and internationally, has certainly made me uncomfortable. On the other hand, he has recently clarified that the movement was much more spontaneous than initially thought.

From my point of view, I did provide some strategic and intellectual support to the movement and participated in it daily. Although I couldn’t be there every day during the curfew, on August 3, I went to Shahid Minar to speak after Nahid. I contributed in my own way. Perhaps he is exaggerating my role out of affection.

The way others are blowing it up makes me uncomfortable, and at the same time, some people are using it to insult me. I don’t want to rise to a height where a fall would be catastrophic.

What I did, others did as well, and everyone should be recognized. This was a people's uprising, not my work alone. People from different places played their parts, some of whom we may never even know. Some wrote, some gave interviews, and some sent statements abroad during the curfew.

We were a group of eight to ten people who discussed and made decisions. My role there was significant, but many others contributed to the uprising as well.

AD: Many people have accused Sheikh Hasina of inciting chaos by using the internet from another country. The massive vandalism at 32 Dhanmondi is said to be a response to her statements. But the government isn’t hers, it’s yours. So, whatever is happening or will happen, you’re responsible. Why couldn’t this incident have been prevented?

MA: Yes, you're right; this couldn’t have been avoided. The anger directed towards 32 Dhanmondi, the building, and the statue stemmed from their association with fascism. People couldn’t see Sheikh Hasina or her family members, only a building and a statue. That’s where their anger was focused.

Had the judicial process moved forward, this incident might not have happened, and people wouldn’t have gathered in the way they did. This breakdown of order was an expression of people’s pent-up frustration. With Sheikh Hasina’s provocations, this frustration and protest took a specific form.

Another factor was the resentment caused by her deification of her father. People remember the period from 1972 to 1975, and they didn’t take kindly to her elevating him to such a status.

Our role was to channel this frustration. Justice was the only way to ease it. If the judicial process had progressed, this wouldn’t have happened. We didn’t want the events after August 5 to unfold the way they did, but if we had confronted law enforcement with the people, an accident could have occurred. The morale of law enforcement was still quite low.

If the public had clashed with the military, it could have been much worse, as the military still had a certain degree of trust among the people. It was a delicate situation for us. We knew that intervening could have backfired, but we couldn’t just stand by.

As the situation escalated, with attacks happening in different places and destructive actions starting, we realized we had to stop it at any cost. We engaged social media influencers and political leaders, and from Thursday night, we began sending messages to prevent any further incidents.

We were also concerned that this wouldn’t be limited to the building or statue in Sheikh Hasina’s vicinity. It could have escalated to attacks on shrines or minority families. We took a very cautious approach. While we couldn’t control the protest at 32 Dhanmondi, we did everything we could to prevent attacks elsewhere. After Thursday night, the situation calmed down considerably.

AD: The government of Bangladesh is

being run by young people like Mahfuj, with Chief Advisor Professor Muhammad

Yunus at the top. However, at first glance, it seems as though the country is

being governed by YouTubers, particularly Elias Hossain and Pinaki

Bhattacharya. I've read about the Nazi era, where their forces didn’t directly

attack everywhere but instead provoked the people, and the people would then go

on to attack their neighbors. This could be seen as a robotic mob in motion.

I've asked many people this: Are you trying to turn the people of Bangladesh

into robotic mobs sitting outside, uncontrollable by you? This clearly shows a

failure...

MA: If we have any failures and someone channels that frustration from those failures, then we must take responsibility for it. It’s not about the success of the YouTubers.

AD: So, how do you plan to prevent a recurrence?

MA: The government needs to take a more proactive approach in terms of justice and arrests to prevent frustration from building up in society. When there’s frustration in society, it becomes easier to manipulate people from various places.

Our primary task is to identify the sources of this frustration. There are many, such as among the families of martyrs. Not everyone knows whether their loved ones' killers have been arrested or if justice has been served. The judicial process itself is something we have limitations with.

The ICT tribunal is ongoing, and because we want to maintain international standards, we can’t deliver a verdict in just six months. Sheikh Hasina might have been able to, but we can’t. The UN and other international organizations are watching us, and we want them to see that we are serious.

We've made provisions for international observers, and international lawyers can participate in the ICT tribunal. This process is long-term, but people don’t have that kind of patience. This is a post-uprising situation, where we know thousands have become martyrs, and 15-20 thousand have been injured, so frustration is inevitable.

This is the current state of Bangladesh, particularly in urban areas where many people have been shot. There's still a suppressed frustration among the people. And against that frustration, there must be justice.

AD: So, does that mean the longer justice takes, the more frustration will build?

MA: Actually, the frustration will subside. No one will be able to manipulate people. For example, consider the issue of border killings. I can’t directly address it with India. Many are saying, "Let’s go to the border." People are thinking, "If the government can’t do it, we’ll do it ourselves."

People act based on what they believe the government can or can’t do. Our government has a six-month timeline. I became a minister in November, and from what I understand, when the public (some people are now referring to them negatively as a "mob," but I don’t want to get into that debate) sees that we’ve taken the initiative, they feel reassured.

We’ve launched the "Devil Hunt." We will carry out Operation Devil Hunt. The Ministry of Home Affairs has taken the lead, and arrests will be made if necessary. You’ll notice that attacks aren’t happening everywhere now. Why is that? Whenever people see that the government is active, they become disarmed and passive. Even if 10 more YouTubers speak out, people won’t take to the streets.

AD: The "Operation Devil Hunt" began with the Gazipur incident. Won’t this suppress opposition voices?

MA: No, no. We’ve repeatedly discussed that we don’t want any extrajudicial killings. Even if just one or two people are involved, we will make every effort to identify the accused, but we don’t want them killed.

No extrajudicial killings will occur. In this case, those breaking the law and taking matters into their own hands will be arrested. Cases will be filed against them, and the judicial process will proceed based on their actions.

Those involved in sabotage, attacks, or who fired shots directly are being brought under the law across the country. This is our main task. Let me be clear: our primary job is to ensure that no one is killed, unlike what Hasina used to do. Our goal is to resist them, imprison them, and bring them into the judicial process.

AD: During the uprising, in the chaos, many terrorists broke out of jail. Have they been identified, listed, and returned to prison?

MA: Some of them have surrendered, which I read about in the news. However, I’m not sure if the entire group is back in jail. A portion of them have surrendered, and those who had weapons have returned them.

We’ve recovered a significant number of weapons, but some are still in people’s hands. We can’t say exactly who possesses them. For example, in my area, I’ve heard that all the weapons taken from the police station have been recovered.

Many prisoners have been released, and they are aware that they’ll be arrested soon, which is why they are surrendering. We are seeing cases of surrender in Narsingdi, and I can verify this and provide more information later. I don’t have the documents with me, but the Ministry of Home Affairs has more details.

AD: According to a BBC report, 96

people died in mob lynchings in Bangladesh from August to December. What is

your take on the law and order situation in the country?

MA: We haven’t achieved the expected improvements in law and order. The police aren’t active enough. The army can only use lethal force, and they can’t control riots effectively. They also don’t have detailed knowledge about specific areas because they are stationed in cantonments.

The police, however, have their own sources and more hands-on resources. Their relationship with the local administration is also different. So, this is a failure on the part of the police. We believe we haven’t been able to reactivate the police force as we should. There are also other factors at play. A significant portion of the police were aligned with the Awami League.

AD: Are they still there?

MA: Yes, they are. We haven’t removed them directly because doing so could cause problems. However, we’ve removed those who were directly against the public or involved in criminal activities. The rest, we may try to identify and address gradually.

AD: How long will it take to reactivate the police?

MA: It’s a process. For example, the mob lynchings are very unfortunate, but they’re not a new phenomenon in Bangladesh. This kind of thing has happened before, even prior to the uprising. In some areas, if there’s a robbery, people might kill someone, accusing them of being a thief.

But these incidents aren’t always politically or communally motivated. While I don’t see it as a widespread communal issue, there have been a couple of isolated incidents. As for political mob lynchings, they might have happened up until around the 5th, 6th, or 8th of August, targeting people from the student league or attacking their offices.

However, mob lynching as a culture is condemnable. It’s a practice that’s becoming more ingrained. People beat someone, claiming they’re a thief, and after the beating, the person might die in the hospital.

Such incidents aren’t just happening now; they’ve been happening regularly. Why? Because I can’t reactivate the local police administration. People have some respect for the army’s presence, but maintaining law and order is not the army’s responsibility. The army cannot control law and order.

AD: So, in a way, the army is an outsider?

MA: Yes, the army doesn’t know how to operate within a village. They are stationed in police stations, but if an incident happens 15 km away from the station, they won’t be familiar with the area. Let’s say an attack occurs at night. How would they get there? They don’t have local networks or associations.

The police, on the other hand, have strong networks. They have a system for gathering information quickly. Because of this system, they can respond to incidents in about 30 minutes. But the army hasn’t developed this capability in the last six months. The idea that the army could develop such a capability is unrealistic. The police and the army have different roles to play.

AD: You are an advisor without a ministry. Does this mean you have responsibility without power, or power without responsibility? What exactly are your areas of responsibility?

MA: When this government was formed, two students were given ministries. The rest of the ministers include former political activists, social workers, human rights advocates, technocrats, ex-bureaucrats, and former military personnel. My role is to focus on political issues.

The government carries certain political responsibilities, and for the past four to five months, I’ve been overseeing whether those responsibilities are being fulfilled. I communicate on behalf of Professor Yunus. I started as a special assistant, and now I’m an advisor.

As a minister without a portfolio, the issue of having a specific ministry never arose. This setup has been in place since November, which allows me to attend cabinet meetings and at least voice my opinions on the policies being formed.

AD: There are accusations that your government doesn’t go to the districts. What do you have to say about this?

MA: There are both positive and negative aspects to this. If we go to the districts, some will say that we are engaging in politics or trying to divide the party. On the other hand, if we don’t go, that’s criticized too. When a minister visits a district, the local administration tends to get energized.

For a week or two, there’s a certain level of enthusiasm. However, this doesn’t happen with us because the government operates from the top down—from ward-level leadership to the ministers and prime minister. But there are only 24 of us in total. For example, the mayor of Chittagong is one of us, but he doesn’t even have a ward councilor. He’s managing everything. Our primary focus is electoral reform—advancing the justice process, organizing elections, and then moving forward.

AD: Isn’t maintaining law and order

and controlling commodity prices part of your responsibility?

MA: Yes, maintaining law and order and controlling prices are definitely our responsibilities. But to manage these effectively nationwide, we need to have the capacity to do so. We don’t have businessmen on our side. Businessmen are connected to certain parties. They follow those party lines. Teachers are also aligned with certain parties.

People don’t listen to us as much because we lack those connections. The Awami League has these connections, the BNP has them, and Jamaat has them. If any of these parties were in power, they could use their connections to influence these sectors. I don’t have that advantage.

Our approach is more about managing things from the top with good intentions. People see me as acting with good intentions. They will say the Yunus government is doing well, but we (the people) aren’t allowing them to work. People blame us personally, but not the Yunus government.

The government is responsive—if something happens, we act immediately. If an issue is trending on social media, we address it the next day. People know that the 24-25 advisors in this government are motivated by good intentions. However, simply having good intentions isn’t enough to run a state, and that’s where our challenge lies.

AD: What action has been taken so far regarding the attacks on religious shrines?

MA: Several cases have been filed regarding the attacks on religious shrines, arrests have been made, and we are working to ensure these incidents fall under the purview of the law. Where vandalism has occurred, we are identifying the damages and looking into whether restoration is possible.

We are also recording statements from those involved in the vandalism. For the incident in Savar, the Police Bureau of Investigation has conducted a high-level investigation. We are not letting this issue go. At the same time, Hefazat-e-Islam has issued a statement, although it came somewhat late, but we believe this matter will be largely resolved. We don’t anticipate this happening again, and we hope that such incidents will decrease in the coming days.

AD: People are saying that part of the government doesn’t want elections to happen, and Jamaat also doesn’t want elections. How do you respond to this comparison?

MA: That’s an oversimplification. The party and the people are two different things. This government has no intention of staying in power for an extended period. The government is set to remain in power for a limited time.

Based on the reports from the Reform Commission, it will stay only for a specific period. Two timelines have already been set: one in December and one in June. Beyond that, there are no plans to extend the government’s tenure. This is very clear. As for Jamaat, it’s going through a transition.

For the past 15 years, it has been unable to access many areas, but now it’s trying to assert itself in those regions. It aims to challenge the BNP, that’s all. Jamaat definitely has an interest here. If the election is held on the 28th, Jamaat might gain 10 more seats.

But is it our responsibility to increase Jamaat’s seats? That’s not our job. My responsibility is to create a roadmap, and within that framework, political discussions will take place. The BNP, its allies, and all other parties are part of that. If they believe the election should be in December, then it will be. If they think it should be in June, then that’s when it will be.

AD: How will you proceed with the election process if the police remain inactive?

MA: This is the biggest challenge we are facing right now. Everyone wants the elections to happen quickly, but if elections occur in this environment, it will only lead to more conflict and violence. The report from the Police Reform Commission has come through.

We plan to work on that and make efforts to reactivate the police force. We’re planning to create local connections between the police and the public, including students. We will identify members within the police force who are involved in criminal activities (if any) and offer amnesty to the rest.

This way, no one will be able to discredit the police. Another important measure is changing the police uniform. The blue police uniform itself can be traumatic. It has personally affected me. The sound of helicopters still makes me uneasy. During the curfew, helicopters would fly overhead, and that sound would signal shootings, which left lasting trauma.

Many people might dismiss changing the uniform, but it does matter. I personally feel uncomfortable when I see that color. It’s a psychological issue. Before I came to power, I was afraid of the police. Wouldn’t I still feel that fear? I understand the psychological distance that needs to be bridged.

Changing the uniform is crucial for that reason. A color change would reassure people. At the same time, we need to identify the perpetrators as quickly as possible.

We also need to revitalize our institutions to make these processes faster. We are doing our best, but we may not succeed immediately—it will take time. Eventually, we’ll reach that point, and then the problems will be resolved.

Providing immediate financial assistance to the families of martyrs and the injured is also critical. Once that’s done, no one will be able to make an issue out of it. We have about 8-10 key issues to resolve. If we can address those, the public will feel reassured and will want to return to a peaceful life.

AD: A large section of Indian legacy

media is claiming that Bangladesh has fallen into the hands of extremists.

Additionally, there are those who campaign for votes under the Hindutva banner

and carry the legacy of Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League—these groups seem to be

part of the same ecosystem. Meanwhile, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s house is being

destroyed, and people are seen wandering around all day with flags bearing the

kalima. How do you challenge this visual and the narrative associated with it?

MA: We’ve addressed this before. In September, there was a surge in the display of black flags. At that time, we took strict measures, and the issue was halted. It’s clear sabotage.

There is a betrayal of our movements happening. If you look at the protests at 32 Dhanmondi, you’ll see non-hijabi girls, girls in pants and shirts, and even girls wearing tops—participating in the protests.

AD: But the TRP is with the flags bearing the kalima!

MA: Yes, they are leveraging this, and those carrying these flags are allowing it to happen. They are pursuing this based on a very specific agenda. Why were we able to stop it at that time? We identified two or three individuals. What did they do?

They joined student processions and inserted these flags into the mix. They would hide the flags in their pockets. We identified and removed these individuals. In large movements, various flags can appear, like red or black flags. Flags can come in many forms.

There’s no issue with a flag bearing the kalima—anyone can put it on a flag if they wish. But their flag style is distinct; it’s the same style used by ISIS or Al-Qaeda. They’re trying to create that association. They want to project the image that this crowd is aligned with them.

They even raise funds by portraying these images. It’s deception, with no truth behind it. Bangladesh’s movement has been progressive, non-binary. Left-wing and right-wing individuals both participate, but neither side has taken over.

That’s our success. We can say it’s neither strictly left nor right—it's a centrist position. We aim to maintain that. Sure, we’ll face challenges, but we’re working toward it.

AD: How involved are you with the new party? Theoretically, ideologically?

MA: Theoretically, I may hold many viewpoints, and some of those may be followed, but I am not personally going out to participate.

AD: If you do participate, people might say you're following in Ziaur Rahman's footsteps by taking the party out of the government...

MA: No, we won’t do that. Those outside the government or those who leave the government will make those moves. Thought is a flow; you can’t stop people from thinking.

If we think about something here, it might influence a political party. We won’t engage in activism, but everyone has the freedom to think. Even government representatives have their political affiliations, whether with the BNP or Jamaat, and there's no issue with that.

AD: After the election, what will your next profession be?

MA: I might go into politics.

AD: So, you plan to join a new party?

MA: I might join a new party, or I might pursue something else.

AD: Will you join BNP?

MA: No, I mean...

AD: You won't join BNP. It seems unlikely that you'll join Jamaat either. There's no possibility of you joining the Awami League either. So, where will you go? Will you join a new party, the one whose ideological structure you're currently building?

MA: I'm not saying anything right now. However, a new party is definitely an inspiration. We need inspiration. We're all giving our blood, and we are united in a shared possibility. And we're fresh blood—no one has corrupted us yet. We want to keep this potential alive. It's essential for us.

AD: There is someone in the government who has Chanakya’s wisdom. Many people rely on his intellect. He exchanges ideas. But would you call the party a kings' party?

MA: Our government has many advisors who are directly aligned with BNP or Jamaat. They’ve written in their favor at different times and may still be offering advice, sharing ideas. I can’t just create a party based on intellect alone—that's actually impossible. There are countless tasks in the field.

There are stories of hardship in the field. You have to go to the ground, talk to everyone, manage money, handle leadership. A kings' party uses the state's resources. I won’t let anyone use the state's resources for that purpose.

A kings' party uses state funds. We won’t allow that either. If we’re talking about intellect, it’s a flowing thing. It can go anywhere. I might write, and they might find inspiration from that writing. But beyond that, I won’t finance it in any way. We won’t offer government auditoriums or other privileges. That’s our policy.

AD: I read in a report from Prothom Alo that many journalists' press ID accreditations have been canceled. You all seem unwilling to accept this.

MA: The press accreditation has been canceled only for entry into the Secretariat. Apart from that, everything remains the same. They can still practice journalism. When you hear "press accreditation," you might think that they can no longer do journalism, but that's not true.

It’s only the card required to enter the Secretariat that has been revoked. Let me explain what was happening at the Secretariat. Under the name of press accreditation, many Awami League and student league workers were given these cards.

As a result, we find that the number of journalists in our media—combining electronics, TV, and others—could be around 150, but do you know how many press accreditation cards there are? Three thousand! How did that happen?

For example, "Noakhali Prabhat" is a newspaper name. Someone could open a newspaper, pose as a reporter, and maybe engage in brokerage or secure tenders. Those who have been identified can no longer enter the Secretariat and question the ministers. But beyond that, they are free to ask questions anywhere else in Bangladesh. That’s all.

AD: Let me mention a few more names: Editor of TV Today, Manjurul Ahasan Bulbul; Editor of Daily Kaler Kantho, Imdadul Haq Milon; Head of News at News 24 Television, Rahul Raha; Chief of News at ATN News, Nurul Amin Prabhas; Deputy Editor of Daily Destiny, Sohel Haider Chowdhury; Chief Editor of DBC News, Manjurul Islam; Senior Reporter of News 24, Joydeb Chandra Das—are they all part of the Awami League?

MA: A part of them, a large part, is from the Awami League.

AD: Can't this be reconsidered?

MA: They were involved in the previous government's propaganda. Now, unless something is proven against them, why should we arrest them? A large portion of them hasn't even been arrested. They're still practicing journalism. The issue of accreditation being canceled only applies to entering the Secretariat.

AD: But Prothom Alo didn’t report this. So, are you suggesting that Prothom Alo spread a false narrative?

MA: They didn't provide the full context. I'm not the Information Minister, but the explanation we have is that the accreditation card was required for entering the Secretariat. The Secretariat is a highly sensitive area for us.

Other than that, they are free to continue practicing journalism in Bangladesh, and there’s no issue with their reporting. Perhaps 4-5 journalists have been arrested, and there are specific allegations against them that will be addressed. There hasn't been a widespread attack on journalists—just isolated incidents.

After August 5-7, many attempts to attack were thwarted by our intervention. When the attack occurred in front of Prothom Alo, the new, changed Bangladesh saw the police take action for the first time.

People used to despise the police, but they were the ones to carry out the first baton charge. You can watch the video of that baton charge. We are doing everything we can to ensure no attacks on Prothom Alo or any media outlet.

AD: So, is there an invisible boxing ring between you two, with two boxers on either side? One named Hasnat, the other Mahfuz Alam?

MA: (Laughs) No, it's about mindset. I am in the government, so I have to provide a responsible statement or have a clear line of thinking. Our perspectives are different. His perspective is rooted in the field, driven by the immediate excitement of the ground. He has to lead from there.

But

we don’t have to lead from the field. Our responsibility is to lead the

government. And that’s what I’m focused on. Our lines of thinking differ. I

focus on the long-term, prioritizing long-term gains over immediate ones.

AD: But won't people draw comparisons between this war-like mentality and the history of Mujib's Rakshi Bahini (Guardian Force)?

MA: We've already addressed this issue over the past six months. There have been proposals and attempts to stir up a warlike mentality, but we have prevented that from happening. We've learned from the experiences of JASAD and the Rakshi Bahini. We don’t want to repeat those experiences.

Our goal is a democratic transition, and that’s why I’ve said our thinking is different. Some might want to lead the people, and that’s possible, but our approach is to work democratically. Whatever we do, we’ll do it openly and democratically, without any secrecy.

We will tell the people exactly how we want to approach politics, and what our potential is. We don't want to repeat the mistakes of JASAD, Rakshi Bahini, or Gonobahini. Our situation is different because we are victorious. We have succeeded within this revolution.

We don't face the same crisis as before. There's no Sheikh Mujib here. We have advisors like Faruk-e-Azam, a freedom fighter who used to organize Bijoy Mela (Victory Fair) in Chittagong. He says that in 1974, they were called Razakars (collaborators).

The Rakshi Bahini chased them, beat them, and left marks on their bodies. They had to flee. They were labeled as Razakars. He was also part of Operation Jackpot, which was against the Pakistani Navy. You won’t see such clashes here. We never had Mujib's force, JASAD, Rakshi Bahini, or Gonobahini, and that is a huge success for us.

AD: What does the future hold for the leftists in Bangladesh?

MA: The future of the leftists will be determined by the reformists. They’ve become somewhat apologetic in their approach after 15-20 years of experience. They once had an inclination toward the Awami League.

A faction of the CPB (Communist Party of Bangladesh) and the Student Union have split. They’re trying to become revisionists, attempting to revive Maulana Bhashani’s legacy. The CPB had erased his legacy before.

There was also a political line from the NAP (National Awami Party)—one faction followed Mujib and another followed Bhashani. Now, a faction of CPB and the Student Union is trying to reclaim Maulana Bhashani’s legacy, but they’re weak within the CPB. For now, they’re more of a resisting force.

AD: But won’t their ideas be useful in the future?

MA: Whether their ideas will be useful depends on their position. When you try to reform within an ideological sphere, you end up cornered. It’s like a flock of sheep—you start to think that sticking to old ideologies might have been a better choice.

Like Jamaat, part of them wants to distance themselves from the 1971 stain. They have a dark history, and they want to move beyond it. But another faction within Jamaat warns them, saying, "You’ll break away, but Awami League will still come after you. You can’t escape the stain of 1971."

Similarly, when some in the CPB and the left try to break away, others tell them, "No matter how much you try to be 'left' or align with Jamaat or the Islamists, it’s futile. They’ll still label you as atheists and persecute you." It’s a very complicated equation in Bangladesh.

Before any possibility arises, it’s often extinguished. For instance, the Shahbagh-Shapla issue. I thought it was resolved in my speech, but now I see it resurfacing. Everyone is once again playing the old politics of division. This isn't what we wanted. We hoped for a resolution.

The people’s uprising was seen as a new beginning. But Jamaat hasn’t admitted its mistakes, and those involved in Shahbagh haven’t taken an apologetic stance either. The new radical Islamists couldn’t create a space where Shahbagh and Shapla could come together.

No one is giving an inch. The old game has resumed, and the debate over 1971 is back. People are either for or against Shahbagh. The crisis has become painful for us.

AD: If BNP wins 250 seats and comes to power, will Bangladesh move toward a one-party system?

MA: We should work to prevent that from happening. If that is avoided, it will be due to the political leadership of the students.

AD: Will the new party be able to

fight against the big powers? How will the funding come?

MA: There are financial realities to consider, and public opinion also plays a role. In urban areas, BNP will get fewer votes. Jamaat might get votes in some grassroots areas, but in urban areas, they won’t have much support.

Jamaat has some votes in certain districts or sub-districts, but they don’t have a national vote bank. On the other hand, BNP has a national vote bank, though they tend to get fewer votes in urban areas. In urban spaces, secularism is more prominent. In urban areas, we’ve actually won. This is an urban movement, though it hasn’t spread much to rural areas. The new party will do well in urban areas.

AD: What is the state of the people's mindset now?

MA: When people live under fascist rule, they carry a deep trauma inside them, a sense of repulsion. We can already see the symptoms of this, and these will persist for the next 20 years.

People couldn't speak out; this suppression will eventually surface in various forms. It could manifest as religious fundamentalism or in other ways, politically, through terrorism, murder, or robbery.

They have destroyed individuals, shattered their spirits. Their dignity is stripped away, and they feel like they are not human. It’s a life of humiliation. Everyone, except those aligned with the Awami League, lives under constant fear.

They could be killed at any moment. It’s a bare existence. All the institutions have been destroyed, and there’s no accountability. Money from the grassroots level has been siphoned all the way to Hasina’s family, which has looted it.

AD: Why have your relations with India become more strained? We're neighbors, and good relations should be desirable, right?

MA: This isn't a new issue—it has been ongoing. India has supported the suppression of anti-Hasina protests, but the state of Bangladesh will remain unchanged. Bangladesh will never be able to dominate India.

AD: Do you think India wants to occupy Bangladesh? No responsible leadership of the state has ever suggested such a thing. Why bring up the views of pro-government media when addressing such an important issue?

MA: No, I don't think India would want to do that, and for good reasons. The people of Bangladesh have always had a rebellious spirit. They are quick to show dissatisfaction, which is why events like ’52, ’69, and ’90 happened, and they have a history of overthrowing governments.

They were once called Boulgakpur. There’s a deep-rooted independent spirit in the riverine villages. As Akbar Ali Khan explains, "I became a Muslim. If you expel me from the Hindu community, I can go across the river and start a new life. I can cultivate land there."

This idea of starting anew doesn’t exist in northern India. It’s a theoretical explanation for why Islam spread in East Bengal. It’s about creating a new identity, a new community, which was a huge struggle. Landlords, 95% of whom were Hindu, had to forge an alternative identity. They were Hindus, landlords, Brahmins, and they wanted to influence people. So, where could I meet them?

AD: Is Islam being integrated here?

MA: Yes, Islam is being integrated, but it's not the same Islam as that of the current Muslims. That’s a long conversation.

AD: Is Bangladesh becoming pro-Pakistan?

MA: If you deny allegiance to India, such narratives will emerge. When Sheikh Mujibur Rahman asked the Indian army to leave, it was because the liberation war linked us with India, but the state didn’t have any allegiance to it.

Yes, we share some affinity with India—it’s normal. We want to be close to the people of Kolkata, Hindus and Muslims alike, and to the people of India as a whole. India has such a large and rich cultural space, why wouldn’t I want to benefit from it?

But I feel trapped by barbed wire, unable to go to India. I don’t want that. I also don’t want to be under India’s control. A friendship with India is crucial for me. My goal is to be friends with the people of India.

This is essential for the freedom struggle of South Asian people. It saddens me that we can’t even go to the Kolkata book fair. Why can’t we go? We should be able to go. I believe Kolkata wouldn't exist without the contributions of East Bengal. The British built Kolkata with the hard work of the people and farmers from East Bengal.

Why can’t we go there? Are we claiming we want to settle in Kolkata, live there, and consume their resources? Can't we just benefit from it? Why shouldn't Kolkata benefit from Dhaka? There has been a deliberate effort to create division. Who benefits from this? Can't Dhaka and Kolkata coexist as separate centers?

During

colonial times, it was Kolkata that introduced modernity to the whole of India.

It holds its own significance, and Dhaka has its own too. Similarly, Chittagong

is different from Dhaka. Shouldn’t we think about how to maintain these

relationships? There are Urdu-speaking people here, with deep roots in Muslim

culture.

But does that mean we are Pakistanis? We’ve rejected Pakistan. In my speech at First Light, I said that Pakistan’s Islam is different from Bangladesh’s Islam. A historian named Abu Mohammad Habibullah, along with Abdul Karim, constructed the theory in the 1960s that Delhi and Dhaka are separate.

We’ve always rebelled against Delhi, against northern India. We don’t accept Delhi’s culture, nor do we accept Pakistan’s. We won’t accept Pakistan’s version of Islam, and we won’t accept the subjugation of northern India. We won’t accept India’s political hegemony, nor Pakistan’s cultural hegemony.

AD: The headline could be that a new Bangladesh rejects the dominance of both India and Pakistan.

MA: Yes, that's right. This is crucial. We don't want to accept either Delhi or Pindi. We want to establish Dhaka as the center. Dhaka will be the hub, the center of civilizational convergence. Many religions have developed in East Bengal, from Nathism and Vaishnavism to a variety of other sects.

AD: Are you referring to Farhad Majhar's theory?

MA: Not exactly. While we might agree on some points, I don’t align with his Marxist ideology. Our politics is more pragmatic. He follows a revolutionary political stance, influenced by Maoist-Leninist thought.

While there may be times we strategically follow similar paths, particularly during uprisings, we don't adhere to that line. Similarly, we also reject Islamist politics. What I mean is, we don’t want an Islamic state in Bangladesh. We envision a democratic state where people from all religions and communities coexist, and where we protect the cultural integrity of each community.

AD: So, you don’t want a religious state?

MA: No, that’s out of the question. Bangladesh has developed its own path. Jamaat-e-Islami will never establish a state here, and an Islamic state will never be possible.

The way Bangladeshis perceive Islam is unique—it might take centuries to change this. This development has been ongoing for 700-800 years. The Arabs came in one way, Persian culture arrived in another, and Turkish culture came in yet another.

Many cultures have converged here. This is the last frontier. If you look around, there are mountain ranges, and below them is the Bay of Bengal. The rivers stop here. This is where cultures finally converge, where debates and discussions happen. Turkish, Bengali, Arabic, Persian, and Urdu cultures are all blending here.

Kolkata, on the other hand, is moving away from Islam. We, however, continue to engage with Hindu culture in many ways. I even practiced Sanskrit at one point. I believe this should remain. Why shouldn’t it? It’s significant to me. Buddhist culture is also important to me.

These are all essential because I need to stand my ground. For the state to stand, this is crucial. A state can never be built solely on one religion. In the context of Bangladesh, a religious or Islamic state is simply not feasible.

—-