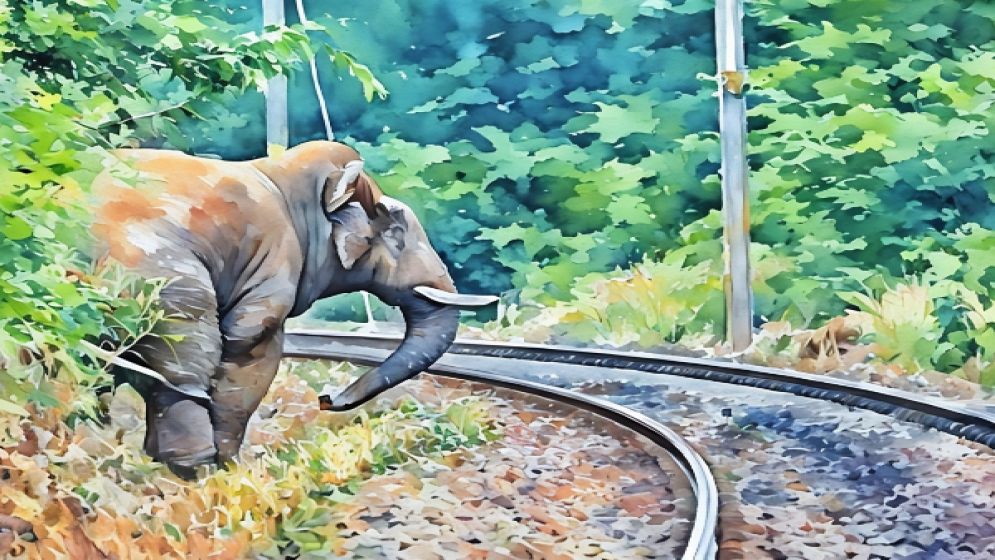

Deadly tracks: How a train line becomes a fatal threat to elephants

The morning mist clung to the trees in the Chunati Wildlife Sanctuary, a veil over the vibrant green canopy.

It was October 13, just after 9:30 am. A herd of elephants, led by their matriarch, emerged from the dense foliage.

Among them, a playful five-year-old calf, full of life and joy, trumpeted softly to its mother.

For generations, this herd had traversed these ancient paths, their route etched into their collective memory. They had no reason to fear the man-made scar that cut through their domain – the railway line.

But that morning, fate had a cruel twist in store.

Suddenly, the tranquility was shattered. A speeding train tore through the forest's silence. In a horrifying instant, it struck the young calf, the impact crushing its delicate spine.

The herd scattered in panic, their cries echoing through the trees, leaving behind their fallen member, the first casualty of a tragedy foretold.

This wasn't just an accident. It was the inevitable consequence of a disastrous decision made back in 2014 – to build a railway line that sliced through three protected forests, including Chunati.

This ill-conceived project, driven by short-sighted development goals, ignored the dire warnings of wildlife experts.

From the very onset, the experts believed that the construction of this railway line was a death sentence for the forest's inhabitants.

It blocked 16 crucial elephant corridors, vital for their movement and survival. Over 720,000 trees were felled, their silent sentinels replaced by cold steel.

The delicate balance of the ecosystem was irrevocably disrupted.

Then that tragic death of that young elephant calf in Chunati Wildlife Sanctuary had happened and exposed the blatant disregard for environmental safeguards in the pursuit of cost-cutting measures.

Lackluster cost-cutting approach

Despite promises and recommendations, Bangladesh Railway (BR) failed to implement critical mitigation measures designed to protect wildlife along the newly constructed railway line.

Nine months after its inauguration, the 27-kilometer stretch cutting through the Chunati forest remained devoid of sound barriers, motion sensors, and green fencing – all crucial for preventing wildlife accidents, especially for elephants.

This negligence flies in the face of the biodiversity baseline survey conducted by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), a major financier of the project.

The survey clearly outlined the need for these measures to minimize the impact on the forest's fragile ecosystem.

Even before construction began, warning bells were sounded.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) conducted a study in 2014, identifying 16 elephant crossing points along the railway line and recommending overpasses at 13 of these locations.

However, in a bid to reduce project costs, BR ignored these expert recommendations. Instead, they commissioned another survey by ADB's international consultant, Norris L. Dodd, who suggested only one overpass and two underpasses.

Adding insult to injury, BR further compromised safety by altering the design of the overpass, making it even more difficult for elephants to navigate.

The Forest Department repeatedly voiced concerns about the underpasses, stating that their height and width were inadequate for elephants to pass through safely.

These warnings, too, were disregarded.

Blatant disregard for wildlife

Professor Kamal Hossen, a renowned expert from the Institute of Forestry and Environmental Science at Chattogram University, condemns the current safeguards as woefully insufficient.

"Two underpasses and one overpass simply cannot ensure safe passage for elephants when there are 16 identified corridors," he argues, citing the IUCN's comprehensive study.

With only 40 to 45 elephants remaining in Chunati Forest, Professor Hossen stresses the urgency of the situation.

"Immediate measures must be taken to slow down trains in the forest vicinity if we want to save these magnificent giants from obliteration," he told Bangla Outlook.

Attempts to reach Md Shuboktagin, project director of the Dohazari-Cox's Bazar Rail Project, for comment were unsuccessful.

Asif Imran, ADB's local environmental consultant, admits to the shortcomings of the current mitigation efforts.

He reveals that the motion sensors, designed for Australian conditions, are malfunctioning in the Bangladesh environment, producing false results.

"We are exploring alternative devices," Imran explains, "and in the meantime, we have urged BR to reduce train speeds within the forest area."

This reactive approach, however, offers little comfort.

The reliance on temporary solutions and the failure to address the root cause of the problem – the inadequate number of crossing structures – paints a grim picture for Chunati's elephants.

—