Railway racket: How Max Group's political ties secured billions in doctored contracts

In the years following Sheikh Hasina's rise to power, Max Infrastructure Limited became one of the most prolific contractors in Bangladesh’s railway sector.

Under the Hasina government’s apparent patronage, the company secured some of the largest government contracts ever seen in the country.

What sets Max apart from other local contractors is its ability to consistently land project after project, despite having minimal experience and a history of questionable practices.

In 2011, Max Infrastructure was a relatively small player in the industry, doing modest construction jobs that barely exceeded 5 to 10 crore taka.

The company, heavily reliant on bank loans, had little to show in terms of major completed projects. Max’s lone accomplishment at that point was a 16.70 crore taka railway line project, one plagued by subpar workmanship. But that year, everything changed.

Max's turnaround came with the intervention of two influential figures in the ruling Awami League: Obaidul Quader and Mirza Azam.

With their backing, Max Infrastructure—a company once limited to small-scale jobs—suddenly found itself at the helm of much larger projects, securing tenders that no one thought possible.

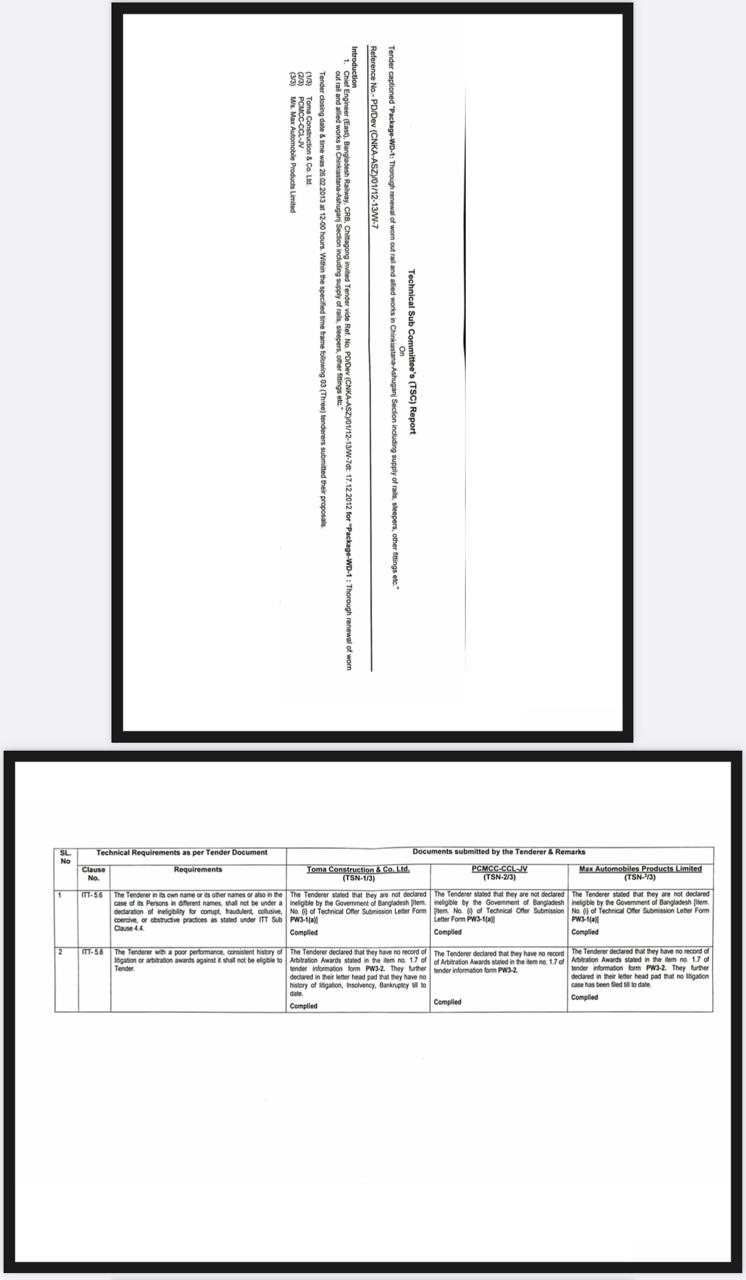

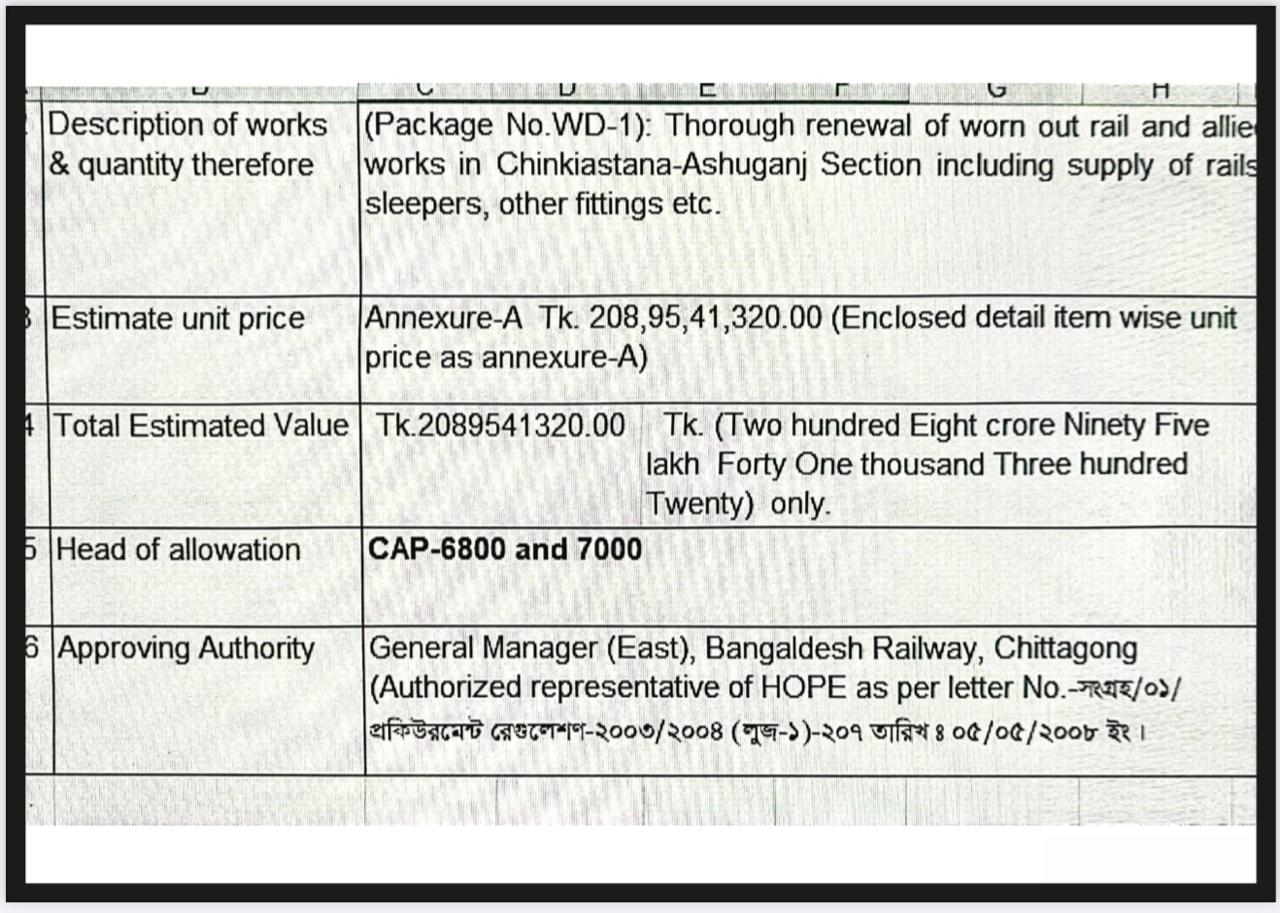

In a move that raised eyebrows, Max secured the Chinki Astana to Ashuganj Renewal Railway Project, valued at 209 crore taka, despite ranking 15th in the tender process.

Max’s rise wasn’t based on merit alone—there were whispers of political influence and fraud. By combining the eligibility of its modest 16 crore taka project with the scope of two other ongoing works worth 50 crore and 96 crore taka, Max essentially inflated its credentials. A written recommendation from the ministers sealed the deal.

It was at this moment that Max Infrastructure began to build its empire. What followed was nothing short of a monopoly.

With the steady backing of Quader and Azam—two men whose ties to the construction sector made them central to the so-called "railway syndicate"—Max quickly began to corner the market.

The rise of Max group

Over the past 15 years, Max has executed projects worth at least 60,000 crore taka, dominating the development sector in ways previously unheard of.

But the intrigue doesn’t stop there. Even as political landscapes shifted, Max Infrastructure continued to control significant portions of the railway sector.

The company retained its position, securing major contracts like the Kashiayani-Gopalganj Railway Project and working on the monumental 18,000 crore taka Dohazari-Cox's Bazar railway project, all while still under the shadow of political favoritism.

What remains a mystery to many is how a company with so little experience in large-scale projects managed to secure some of the most lucrative railway deals in the country.

How did Max, a Grade-4 contractor with no major railway background, secure contracts like the 209 crore Tikka Shikni Lost Railway Project, the 1,800 crore Laksam-Chinki Shikni Railway Project, and the 6,000 crore Akhaura Laksam Railway Project?

The answer, many argue, lies in the unshakeable influence of Quader and Azam—two politicians whose grip on the construction sector has allowed them to reshape the landscape of Bangladesh’s railway industry.

The company’s success story, laced with questions of political meddling and fraudulent tendering practices, highlights the darker side of infrastructure development in a country where the lines between business and politics often blur.

Investigations into Max’s meteoric rise have since peeled back the layers of fraud and political manipulation that underpinned its success.

At the center of it all is Golam Mohammad Alamgir, the chairman of Max Infrastructure.

Once a self-proclaimed major donor to the Awami League, Alamgir’s rise was fast-tracked through his close ties to influential party figures.

His connection to the Awami League government grew stronger with time, and even after the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s administration, he was imprisoned on charges of corruption.

Yet, despite his legal troubles, Alamgir’s hold on lucrative contracts remained unshaken. Under his leadership, Max won contracts not only in the railway sector but also in other major infrastructure projects, including the Dhaka-Sylhet highway improvement project, worth 2,320 crore.

A growing monopoly

In this project, Max worked in joint ventures with Chinese contractors—another sign of the company’s growing monopoly.

Max’s rise wasn’t without competition, though. Toma Construction, another major player in the railway sector, has worked on projects like the Dohazari-Cox's Bazar and Akhaura-Laksam railways in joint ventures totaling 6,161 crore.

The owner of Toma, Ataur Rahman Bhuiyan, is closely linked to the Awami League, having served as vice president of the Noakhali district chapter.

While Toma’s ties to the Awami League’s organizing secretary Mirza Azam were well-known, Max’s unrivaled success in securing high-value railway projects was driven by its deep connections to Obaidul Quader, the former Minister of Road Transport and Bridges.

But perhaps the most significant connection of all was between Alamgir and Mirza Azam. Through this relationship, Alamgir and Max Infrastructure gained an unassailable grip on the railway sector, the investigation by Bangla Outlook found out.

Despite ranking 10th in terms of tender eligibility, Max consistently won project after project, securing as much as 90 percent of the contracts, often without any competition.

Sources close to the railway sector have suggested that these projects came with a steep price: a 30 percent commission paid to the right people in exchange for awarding Max the contracts.

Further investigation revealed the extent of Azam’s control. Over the past 15 years, Azam has managed railway projects worth a staggering 70,000 crore, earning him a reputation as the head of what insiders called the "Sheikh Rehana Syndicate."

These projects were often awarded to third-tier contractors, who, in exchange for the work, funneled large commissions to Azam and other key figures in the network.

The money, sources say, ultimately found its way to Sheikh Rehana, the younger sister of Sheikh Hasina. Alamgir, too, had personal connections with Sheikh Rehana, which further cemented his influence in the railway sector.

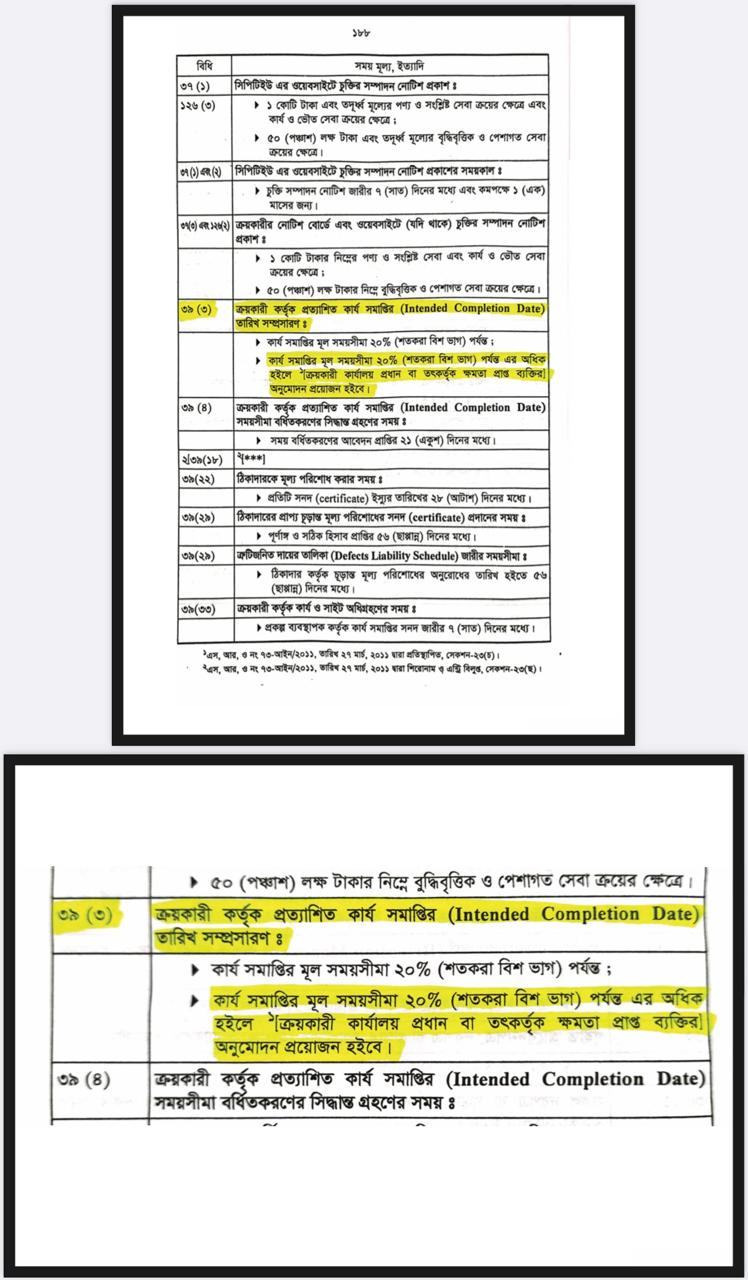

Contracting experts assert that according to the terms of international tenders for joint ventures, a company must demonstrate past experience on projects worth at least 26 percent of the total project value to qualify as a partner.

Yet, Max Infrastructure had no experience even remotely close to this threshold—less than 2 percent of the required project value.

Contracts without proper assessment

An investigation has uncovered that, in the tender process for the construction of the Cox's Bazar railway line, Max submitted fraudulent and ambiguous legal documents, along with overstated past experience.

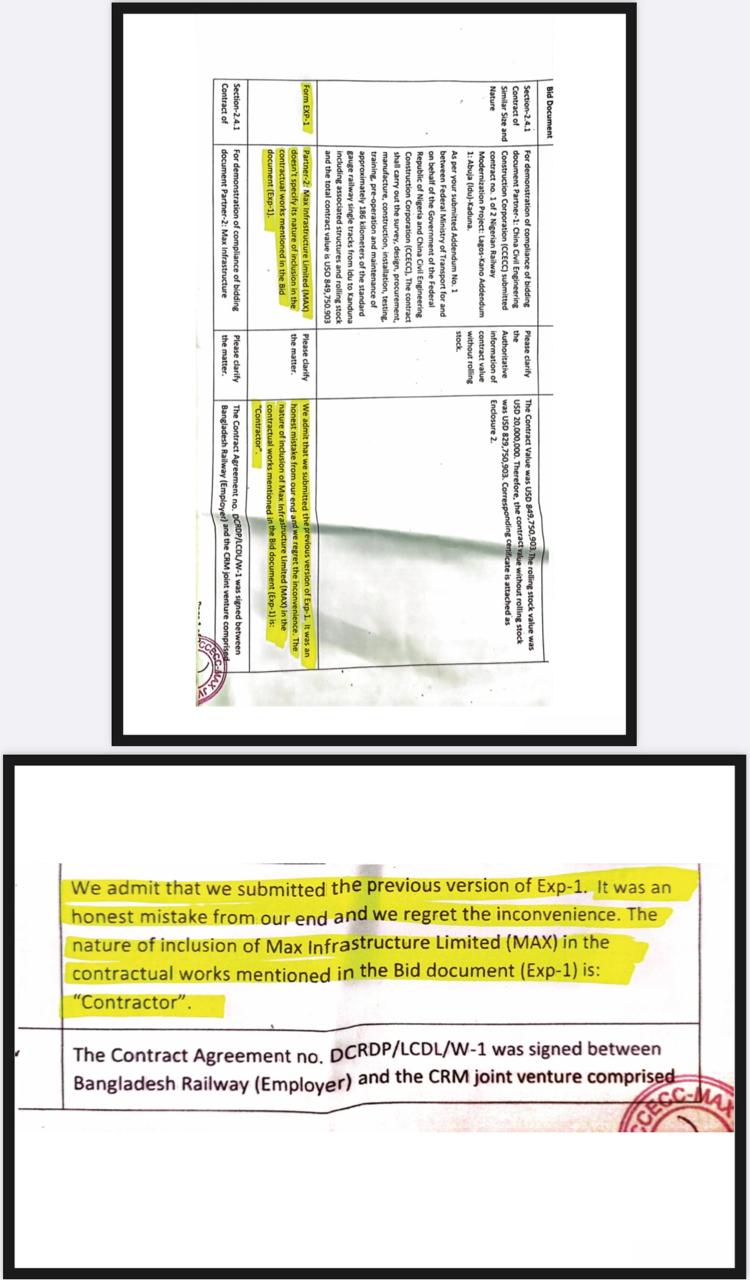

Specifically, they cited their involvement in the Laksam-Chinki Shikni double railway construction project as evidence of their capabilities.

Max initially leveraged the experience of their foreign lead partner, China Railway Material Import and Export Company Limited, to gain entry into the tender.

But they soon falsely claimed full experience in the project, a critical deception that exemplified the scale of fraud in Bangladesh’s railway sector.

A railway official, speaking on condition of anonymity, revealed how the construction of the Dohazari-Cox's Bazar railway line was initially part of a single task in the main project document (DPP) and its subsequent revision (RDP).

In an effort to facilitate Max’s involvement, then-project director Mofizur Rahman and the CEO, Amjad Hossain, split the work into two packages, labeled Lot-1 and Lot-2. Max took on the Lot-2 package in a joint venture with a Chinese contractor, bypassing the usual qualifications and regulations.

The rampant corruption tied to Max and Toma Construction’s involvement in the railway sector led to widespread environmental destruction.

Through their work on these projects, they violated protected forests, devastated hills, and endangered biodiversity.

The government-backed syndicates led by these companies orchestrated what many described as the largest corruption spree in the railway sector.

It was only when Professor Hasib Mohammad Ahsan, a member of the evaluation team from Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET), witnessed the depth of the irregularities, that he withdrew from the project, refusing to sign the evaluation report.

Despite his objections, the projects moved forward with the encouragement of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the complicity of corrupt Bangladesh Railways officials.

A massive web of embezzlement, involving billions of taka in loans, was set in motion through a partnership between Toma, Max, and some key officials within the railway system.

Among the corrupt officials named in the 2011-2016 procurement contracts were Director General Amjad Hossain, Sagar Krishna Chakraborty, Naznina Ara Keya, Liakat Ali Khan, Mofizur Rahman, and Abul Kalam Chowdhury.

In addition, another major contract for the 72-kilometer-long Akhaura-Laksam double line railway, worth 6,504 crore taka, was signed on June 15, 2015. Partners CTM China Railway Group, Toma Construction Company, and Max Limited executed the project jointly.

Notably, the China Railway Group was also involved in the Cox’s Bazar project with Toma.

In cahoot with the bureaucracy

Sagar Krishna Chakraborty, the project director for Akhaura-Laksam, played a pivotal role in the syndicate, further solidifying the corruption network’s grip on the railway sector.

The project director for the Cox’s Bazar railway, Mofizur Rahman, forwarded the project for approval to the ADB without proper verification, bypassing required procedures and excluding TIBER members from the review process.

This set the stage for another round of massive corruption.

Through these deceitful practices, a tightly-knit group of railway officials, two underqualified contractors, and the active involvement of the ADB contributed to the ongoing looting of public funds, ushering in a new era of systemic corruption and mismanagement in Bangladesh’s railway sector.

To qualify for the tender on this project, contractors were required to demonstrate at least one project in the last decade worth $270 million (approximately 2,268 crore taka), with a proven track record in track, bridge, embankment, station construction, signaling, and telecommunications.

In a joint venture, the lead partner needed to meet these qualifications fully, while the other partners were only required to show 25 percent of the total project value in similar experience—around 567 crore taka for a project valued at 2,208 crore taka.

So, the crucial question remains: how valid was the work experience certificate Max Infrastructure submitted, and how did the opinions of the Technical Steering Committee (TSC) bypass the Technical Bid Evaluation Report through Project Director Mofizur Rahman?

And how was the previously incomplete status suddenly deemed compliant?

As the investigation reveals, once the report reached the ADB, Rahman gave full validation to Max's submissions, recommending them for approval.

This marked a key moment in the cycle of corruption that would set Max on its path to securing this lucrative project.

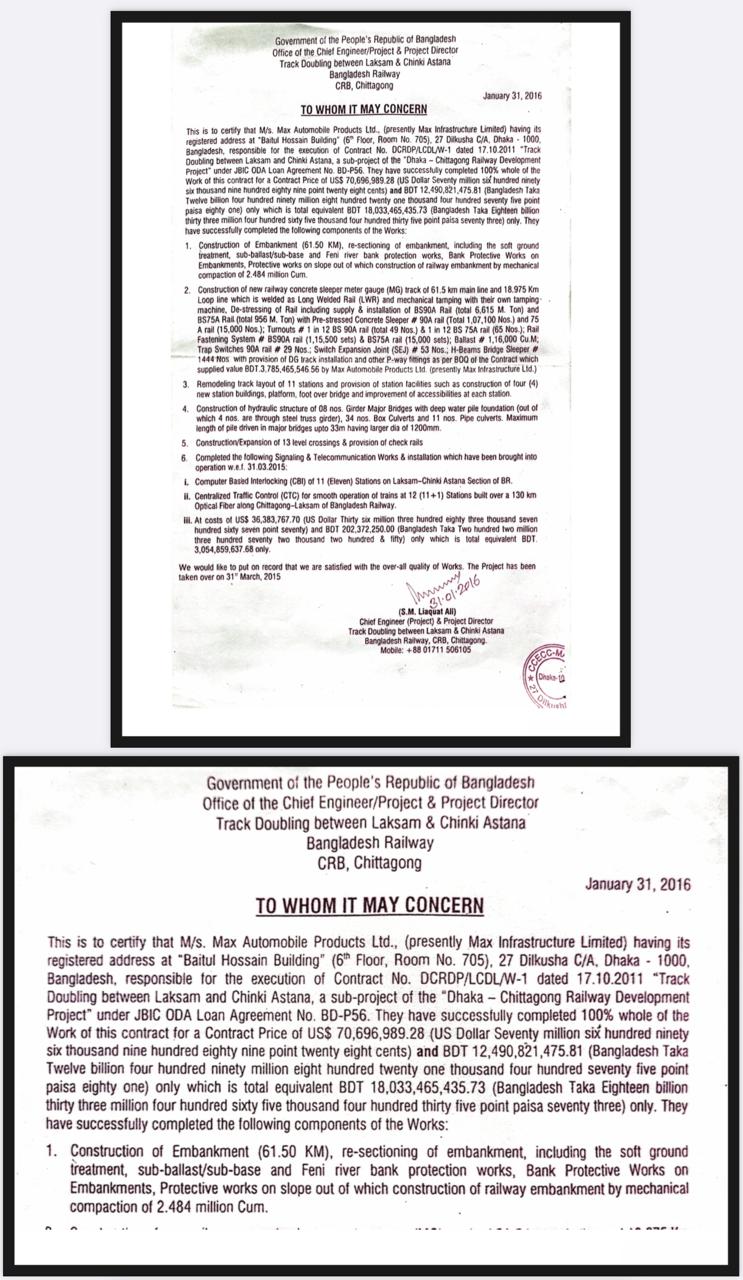

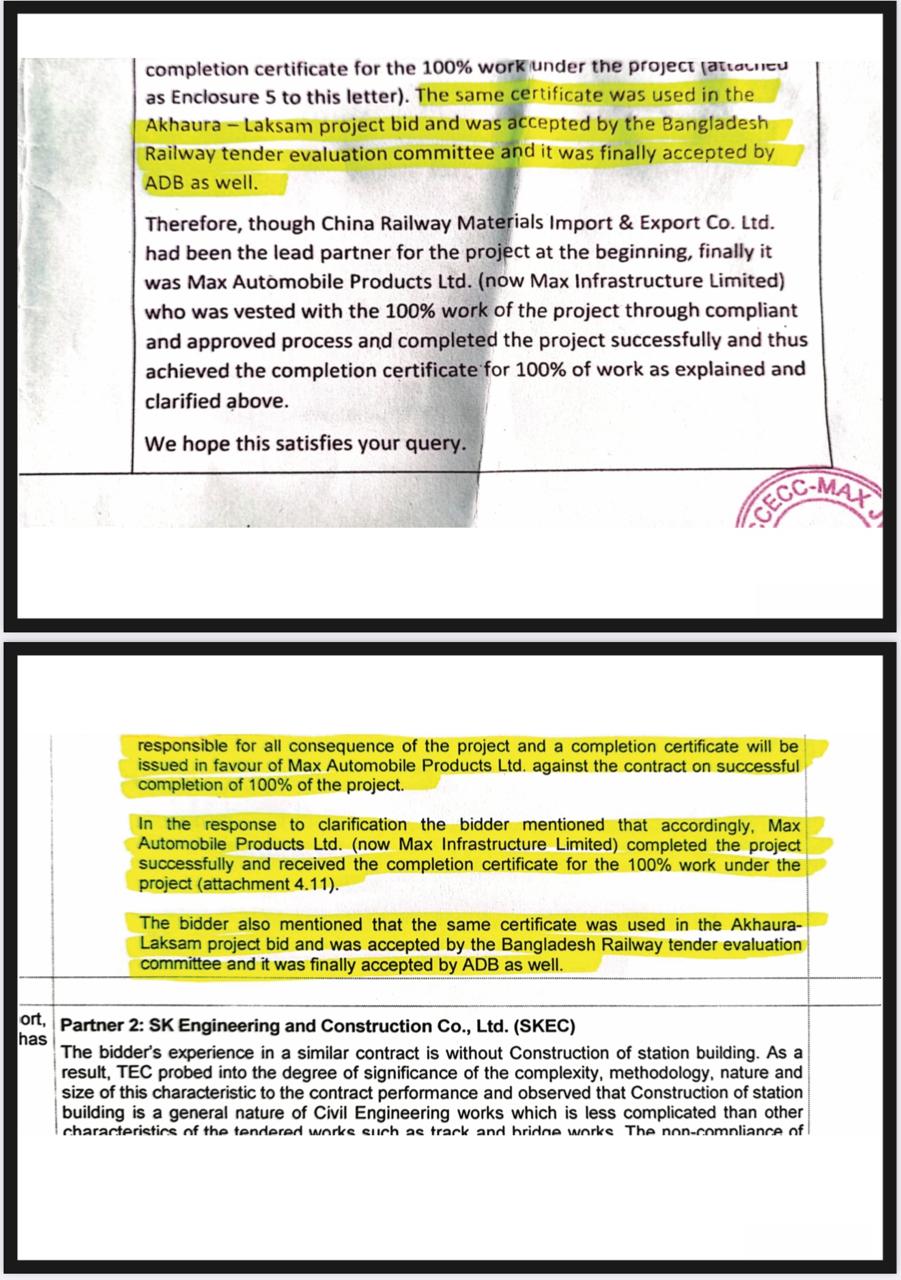

Max’s involvement in the Laksam-Chinki Shikni dual railway construction project began under the CRM Joint Venture Association.

Though they were only a partner in this project, Max stood to gain considerably. Upon completion, the lead partner, China Railway Material Import and Export (CRM), was to receive an experience certificate from Bangladesh Railways.

This certificate would acknowledge Max’s role as a partner, reflecting their share in the joint venture’s work.

A contract for the project was signed on October 17, 2011, between Bangladesh Railways and the CRM Joint Venture Association.

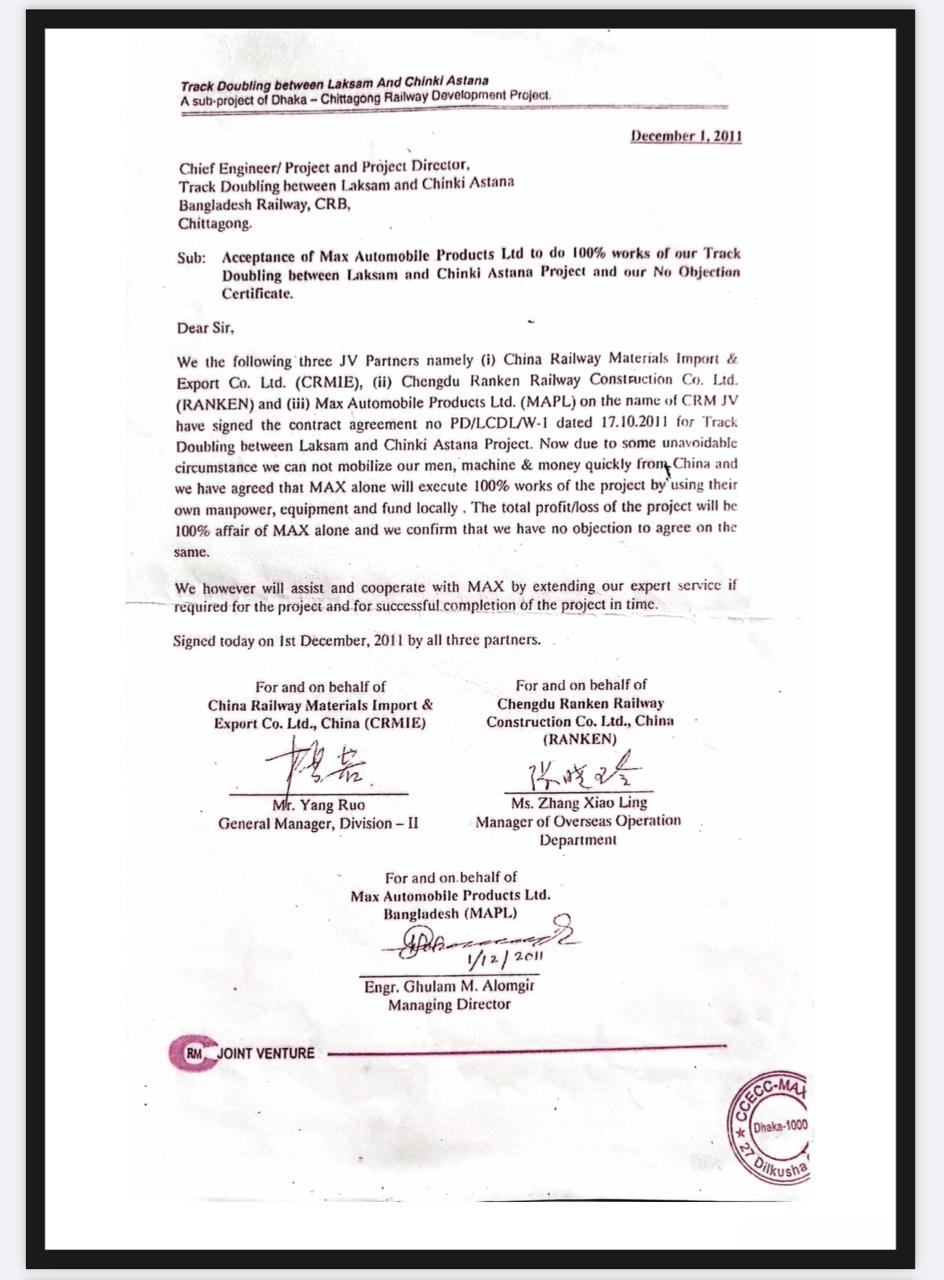

However, just over a month after the agreement, a joint letter from the three companies in the association was sent to the project's chief engineer.

Violating contract and evading

practiced norms

The letter revealed that the two Chinese companies, CRM and Chengdu Railway Construction Company, would be unable to bring in the necessary equipment, personnel, and funds due to unavoidable circumstances.

Consequently, they informed the engineer that Max would take on 100 percent of the project’s responsibilities and would receive the qualification certificate alone.

This decision was later reinforced in December 2011, when Max proactively sent another letter to the chief engineer, requesting an expedited start to the project.

The letter explained that the lead partners would not be able to bring the required resources on time, and thus, Max was again tasked with completing the project independently, according to their internal understanding within the joint venture.

Under the terms of the contract, the companies were jointly and individually responsible for the project. If one partner failed to fulfill their duties, the remaining partner would assume full responsibility.

Max, therefore, found itself tasked with completing the project on behalf of the joint venture—a responsibility it took on despite the apparent lack of necessary experience or resources.

This marked the beginning of Max’s rapid rise within the railway sector, facilitated by questionable arrangements and dubious practices that would allow the company to dominate future projects.

Max Infrastructure had already deposited a 10% performance guarantee on behalf of the CRM joint venture, which included China Railway Material Import and Export as the lead partner and Chengdu Railway Construction as a partner.

However, the parties reached an agreement for Max to take on the entire project, using its own machinery and equipment—a decision that raised serious ethical and legal concerns.

This unilateral move contradicted the terms of the procurement contract and violated procurement laws. It also created an opaque and troubling situation: Max now claimed that it needed a large bank loan to fund the project but could only secure the loan if Bangladesh Railway allowed them to complete 100% of the work.

Following this, Max made a formal request to Bangladesh Railway for permission to carry out the project alone and demanded a 100% competition certificate in its name upon completion.

Through this strategy, Max, with a mere 16.7 crore taka worth of previous work experience, was suddenly positioned to qualify for a 1,800 crore taka project.

The fraudulent maneuver didn’t stop there; it paved the way for Max to ultimately secure the 18,000 crore taka Cox’s Bazar railway project.

Max’s distorted truth

However, there are critical questions surrounding this development: Despite the presence of two well-established Chinese companies—China Railway Material Import and Export and Chengdu Railway Construction—why did Max suddenly plan to exclude them from the project?

Why was such a drastic, contract-violating proposal made immediately after the contract had been signed, particularly when the joint venture had been approved based on the qualifications of China Railway as the lead partner?

Was this proposal part of a premeditated strategy? And why, after the technical evaluation committee’s review before the project award, did they attempt to remove the lead partner from the project altogether?

Such a move seems to defy not only the terms of the procurement contract but also basic procurement laws, which require that the combined experience of all joint venture participants be evaluated before a contract is awarded.

Given that the Chinese companies were initially included based on their extensive experience, how did Max, with its minimal background, get the opportunity to carry out the entire project?

Moreover, can a company receive a certificate of experience solely under such terms, when the work was awarded as part of a joint venture?

Max’s qualification for the 1,800 crore taka project, with only 16 crore taka worth of previous work, seems impossible under the standard rules.

Was the real goal to set the stage for securing even larger projects—specifically the 18,000 crore taka Cox’s Bazar railway project?

Max's claim that its Chinese partners could not supply the necessary equipment or materials was also dubious.

In reality, China Railway Material Import and Export—the lead partner—had already provided the essential construction materials on time, as confirmed by the project’s chief engineer and project director.

They issued a certificate on Bangladesh Railway’s official letterhead, stating that the lead partner had adhered to technical instructions and provided the necessary resources as required.

This raises further questions: What was the true purpose behind the request to exclude the Chinese companies?

How did Max manage to leverage its limited experience and connections to manipulate the system, securing massive projects that should have been well beyond its capacity?

The unanswered questions

The answers point to a broader pattern of corruption and exploitation within the sector, one that allowed Max to ascend in the railway construction industry through questionable practices and powerful political ties.

The evidence clearly reveals that Max’s claims were false. The two Chinese companies—China Railway Material Import and Export and Chengdu Railway Construction Company Limited—were directly involved in the project.

Yet, they purportedly excluded themselves from the process and issued an experience certificate solely in favor of Max.

This assertion is deeply misleading, as the most crucial component of the project—the 7,000 tons of railway tracks—had been supplied by these very companies.

The question arises: How did these two companies, who were actively involved in the project, support the decision to issue a 100% experience certificate for Max, despite their own integral role in supplying the materials?

Equally troubling is the fact that the project’s chief engineer (PD) and the director general (DG) of Bangladesh Railway approved this dubious arrangement.

This approval suggests that the primary intention was to pave the way for Max to qualify for the Cox’s Bazar railway project.

In the case of the Laksam-Chinki Astana double railway construction project, the work had been awarded primarily to the two Chinese companies, who completed it jointly according to the contract.

As such, the experience certificate should have listed all three companies—Max, China Railway Material Import and Export, and Chengdu Railway Construction—not just Max alone.

However, during the certificate issuance process, the project’s chief engineer and director engaged in deception to ensure that only Max would benefit. This manipulation has been documented and preserved by Bangla Outlook.

The procurement contracts between 2011 and 2016, which involved several key officials, including then-Director General Amjad Hossain, Sagar Krishna Chakraborty, Nazina Ara Keya, Liaquat Ali Khan, Mofizur Rahman, and Abul Kalam Chowdhury, were central to this fraudulent arrangement.

When contacted for a statement, Max Infrastructure’s media and communication manager, Ibrahim Khalid Palash, indicated that a detailed written response would be provided. However, despite repeated attempts to follow up, no further response was received from Max’s side.

—-