Maulana Bhashani, his Farakka March and the lasting legacy

Harun Ur Rashid

Publish: 16 May 2024, 06:21 PM

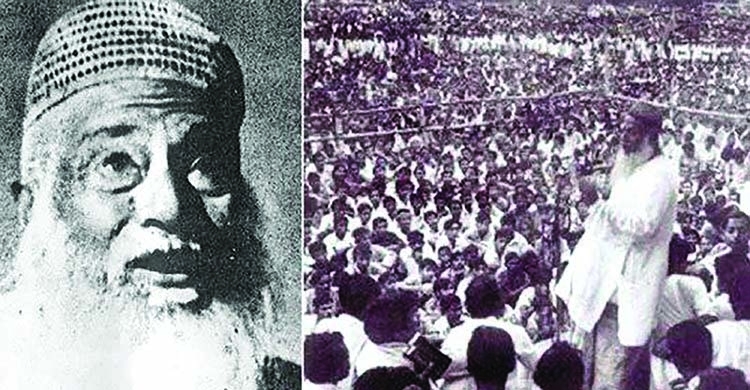

Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani wasn't your typical leader. Clad in his simple white punjabi and signature lungi and topi, he stood in stark contrast to the opulent figures of Bangladesh's ruling class. Hi life wasn't about power or privilege; it was about the land, the labor, and the very language of the poor.

Imagine a person – a champion for the sharecroppers, the fisherfolk, the rickshaw drivers, the jute and sugar producers, the factory workers, the farmhands. Bhashani was the voice of the "Wretched of the Earth," as Frantz Fanon called them – the urban poor, the shopkeepers, the primary school teachers, all those overlooked and neglected.

He wasn't just a firebrand orator; he was a constant presence, a tireless advocate for the oppressed. He became a legend, the "Majloom Jananeta," the leader of the oppressed, arguably the most popular revolutionary peasant leader Bangladesh has ever known.

Bhasani's revolutionary spirit wasn't born in a political rally; it sprouted from the fertile soil of shared struggle. He wasn't just a leader; he was one of them. This became clear when he organized and led poor peasants from East Bengal to a new life on Bhashan Char, a river island in colonial Assam.

There, the red Maulana, as he was lovingly called, lived amongst the people he championed, earning their love and the title "Bhashani" – a testament to his dedication, much like the way the Argentine revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara found a home and a moniker in Cuba.

Historic Farakka march

However, Bangladesh's fight for a better life extended beyond internal struggles. Soon after independence, India's construction of dams and barrages on shared rivers like the Ganges began to disrupt the natural water flow. These "hydro-developmental initiatives" had a profound impact on Bangladesh, a nation at the receiving end of the Himalayan river system.

The lifeblood of Bangladeshi agriculture, fisheries, and public health was threatened by this disruption. While water sharing disputes with India date back to the creation of both nations, a lasting solution has remained elusive, leaving countless Bangladeshis yearning for a future where their land and well-being are not compromised.

In today's interconnected world, it’s a known fact that environmental decline in one region can ripple outwards, impacting the entire planet. This is particularly true with shared resources like rivers. After colonization, newly formed nations often drew borders that divided these waterways, fostering a sense of individual ownership instead of a collective responsibility. Rivers, once seen as a unified system, became fragmented.

Upper riparian states, those located upstream, often prioritize their own needs when managing these shared waters. This can come at the expense of downstream nations, leading to tension and conflict. Bangladesh is a prime example. Many of its 54 rivers originate in India, and upstream dams and diversions have significantly disrupted the natural flow, impacting Bangladesh's ecology, agriculture, and public health.

The construction of the Farakka Barrage in 1975 drastically diverted Ganges water towards India, impacting Bangladesh's agriculture, industry, fisheries, and public health. This disruption to the natural flow has fundamentally altered the river system, impacting not just the hydraulics but the entire ecological balance.

The consequences were stark, particularly in the southwestern region of Bangladesh. Livelihoods are lost, and the very fabric of life in this densely populated river basin – one of the world's largest – is under threat.

Bhasani protested India’s unwarranted water shifting from Ganges river basin. His historic "Farakka Long March" remains a powerful symbol of his righteous fight. Bhasani's legacy is a reminder of the urgent need for cooperation. Riparian nations must move beyond national interests and recognize the Ganges as a shared lifeline. Only through collaboration can they ensure a sustainable future for this vital river basin.

The legacy of the Red Maulana

Maulana Bhasani's place in Bangladesh history is etched in stone. His leadership during the mass movement of 1969 that toppled Field Marshal Ayub Khan cemented his status as a public hero.

Students and citizens across the nation rose in a wave of protest. Their demands were clear: the withdrawal of the fabricated Agartala conspiracy case against Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and a return to democracy. Bhashani, with his unwavering spirit, became the catalyst that propelled the movement forward.

The Bengali population in East Pakistan, under Bhashani's guidance, consistently demanded the release of Mujib and his co-accused. They called for the regime's downfall. Bhashani even advised the imprisoned Mujib (not yet Bangabandhu) to reject Ayub Khan's offer of a conditional release to join a roundtable conference. Mujib, Bhashani argued, deserved unconditional freedom first.

In a bold move, Bhashani threatened the regime with a march on the Dhaka cantonment unless the Agartala case was dropped. This decisive action proved effective. On February 22nd, 1969, the regime bowed to pressure. By March, it was history.

The Red Maulama was an embodiment of restless inspiration. He never sought comfort in the trappings of power, a trait that shines through his entire political career. He remained a champion of the people, a reluctant hero.

However, Bhashani's legacy is complex. Despite being a champion of Bengali nationalism, his call for a "Muslim Bangla" raised concerns about stoking religious tensions in the newly formed secular state. A 1974 speech criticizing a Hindu food minister exposed a troubling inconsistency in his views.

Despite these contradictions, Bhasani remains a significant figure in Bangladesh history. His unwavering commitment to the cause during the Liberation War is undeniable. He never sought power, yet wielded immense moral influence.