Have we reached towards a point of no return?....Probably.

Photo Credit: Nazmul Islam

On my way to Shaheed Minar today, I deliberately stopped by the Dhanmondi office of the Awami League chairperson.

Female activists and leaders were gathered in a circle on plastic stools and chairs by the roadside, while groups of male activists and leaders roamed around Road No. 3A.

Some appeared confident, while others seemed anxious. The discussions on that road were a blend of nervousness, belligerence, and caution.

“We need to take strong action. The student and opposition movements are gaining momentum,” remarked a broad-shouldered, bearded young man in his late 30s. “Let’s wait and see what Quader bhai (Obaidul Quader) says,” responded an older man, who wore a brooch shaped like a boat on his shirt.

A battery of police officers was stationed at the road entrance, with three police cars parked nearby.

Aside from Road No. 3A, Dhanmondi appeared normal, possibly with lighter traffic. The Zhigatola intersection, directly across from the Awami League party office, was congested and chaotic as usual, with a lone traffic officer trying to manage the jam.

-66ae77fb69294.jpg)

A young couple, the girl in cargo pants and an olive T-shirt, and the boy in a black jumpsuit, were hailing a rickshaw. “Will you go to Dhaka University?” the girl asked. The rickshaw-puller nodded, and they climbed in.

The boy glanced at me and gave an odd smile. I returned the smile and boarded my rickshaw, heading in the same direction.

As a light drizzle began and the sky took on a gloomy hue, I noticed about 50-60 people, mostly young, marching towards Nilkhet from the Science Laboratory intersection.

They were chanting slogans: “Chi Chi Chi Hasina, Lojjai Bachina” (Shame on you Hasina; We are dying of shame) and “Amar Bhai Morlo Keno, Khuni Hasina Jobab De” (Why has my brother died, Killer Hasina, give us the answer).

I got out of the rickshaw and started following the group.

More people began joining the procession at Nilkhet intersection, causing the crowd to swell and the slogans to grow louder.

-66ae7841a35a7.jpg)

By the time we reached Palasi Bajar, two additional processions had merged with us, coming from BUET and Eden College.

With the increasing crowd, the slogans grew more fervent and the noise level rose.

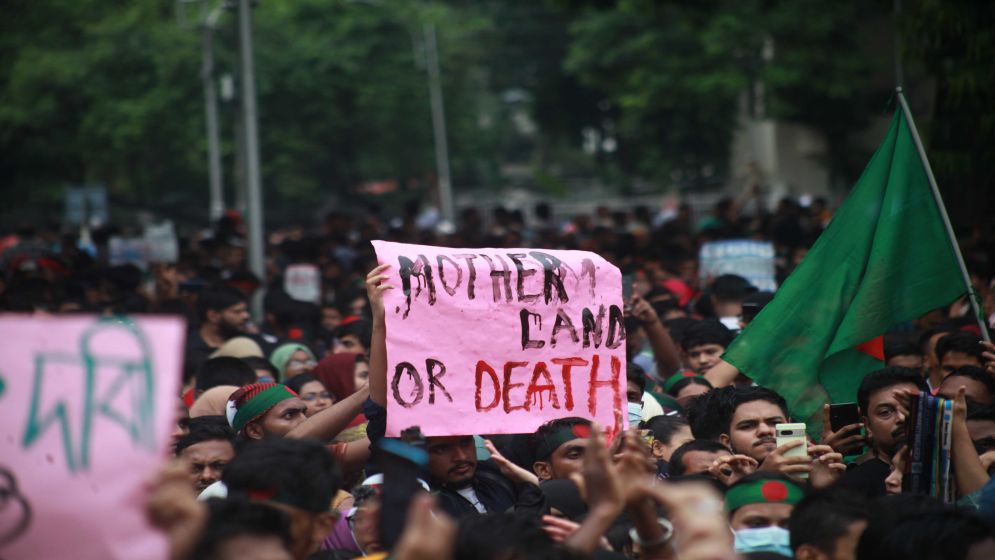

The protesters shouted with clenched fists and determined eyes. Some smiled, nodded to each other, and exchanged silent messages through their gazes. Their message was clear: they were on the streets with a single demand—the resignation of the government.

The four-way intersection near the Shaheed Minar was packed with people.

Several rickshaw drivers parked their vehicles in circles and climbed on top, using them as makeshift platforms to lead the chants. The elevated position gave their voices added prominence. Those on the rickshaw seats naturally took the lead in starting the slogans.

While the rhythmic second lines were chanted with enthusiasm, the collective noise from various groups of slogans created a general roar, making individual chants less distinct. Despite this, no one seemed to mind—the crowd was like a vast sea with many waves.

As I tried to navigate my way through the crowd to reach the central area of Shaheed Minar, where I had heard the main coordinators of the quota protest were gathered, I came across many familiar faces.

Among them were executives from major private firms, aspiring singers, Western-educated Hijabi university professors, and notable figures from the country’s often overlooked transgender community. We exchanged glances, nods, and smiles.

At the base of the Shaheed Minar stairs, a group of young boys, some in college uniforms and others in casual attire but all wearing their college ID cards around their necks, were engaged in a political discussion.

“There’s no way we’re leaving without securing our one-point demand today,” declared a young man with silver-framed glasses. “Absolutely,” agreed another.

Nearby, four striking women in their late 20s or early 30s were singing a beautiful Bangla song. Though I couldn’t catch all the lyrics, it was about breaking doors—not Nazrul’s famous “Karar Oi Louha Kopat.”

One woman in particular drew my attention: her face, slightly sunburned and adorned with the words “1 dofa (one point), 1 dabi (one demand),” looked especially captivating.

At the center, there were many familiar faces along with the coordinators of the student-led quota protest. Nahid Islam was the most recognizable figure among them.

-66ae78a1323f9.jpg)

Just a few days earlier, photos of his bruised thighs, marked with purple and red, had been circulating on social media. I wondered, “Has he fully recovered?” I speculated that perhaps he no longer felt the pain due to the adrenaline rush.

At some point—it's hard to recall exactly when, as time seemed to blur in the midst of the crowd—Nahid officially announced the one-point demand: The government must step down. The crowd responded with an enormous cheer.

I felt a mix of emotions: sorrow intertwined with apprehension, joy, and excitement. While the future remains uncertain, it was clear that this crowd was resolute and had reached a point of no return.

I couldn’t help but wonder if those sitting or wandering around Dhanmondi 3A, in front of the Awami League party office, were aware of what was unfolding.

—-