Morgue, journalist Priyo's body, and the memories of the long July

Asif Bin Anwar

Publish: 14 Sep 2024, 08:23 PM

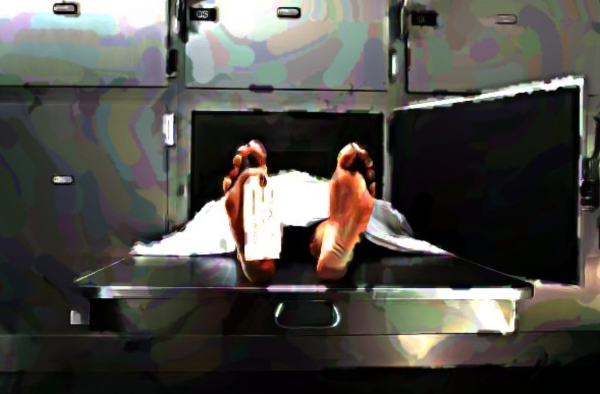

A solitary, single-story building stands, marked only by a chilling sign that reads 'Morgue'.

Just beside it, a smaller structure draws a jostling crowd - the morgue's office. Three or four security guards struggle to maintain order amidst the throng.

Inside, a glimpse reveals a cramped space. A narrow table occupies the front, where two or three employees sit on a bench, engulfed by a sea of around twenty people.

Everyone leans forward intently, refusing to yield space, creating a palpable sense of disorder. Yet, instead of the anticipated cacophony, an eerie, slow silence hangs heavy in the air.

On the morning of July 20, around 11:30 am, we arrived there–at the Dhaka Medical College Hospital morgue office– searching for Priyo.

Tahir Zaman Priyo, my wife's nephew, was the son of her cousin Koli Apu. He was around 28 or 29 years old and worked as a journalist for an online news portal.

Priyo was slender, always with a shy smile, and had recently finished his student life. Throughout his student life, he was involved in various movements.

The night before, around 10 o'clock, fragmented reports suggested Priyo might have been shot. Later, it was confirmed that he was dead, and the police had taken his bullet-riddled body. The incident reportedly happened in front of Lab Aid in Dhanmondi.

We were advised to check Central, Lab Aid, and Popular hospitals, as the police often take bodies to the nearest hospitals first.

Curfew started at midnight on July 19. The

internet had been shut down for two days, and no news came from the hospitals.

We inquired with police acquaintances about any bodies matching Priyo's

description at Dhanmondi or Kalabagan stations, but they had no information.

In the morning, we received reliable information that Priyo was at the Dhaka Medical College Morgue. The curfew would lift from 11 o'clock for two hours, so my father-in-law and I rushed to get an ambulance. We picked up Mitul Apu, a friend of Priyo's mother, on the way.

Upon arrival, we found Shreshtha, our other nephew and Priyo's cousin, already there. One of Priyo's aunts had also been there earlier. We couldn't find Priyo's name in the register, so I suggested checking the unidentified list.

The list described about ten bodies, identified only by serial numbers and corresponding counter labels attached to each body. Shreshtha shortlisted two based on age, time, etc., and went to identify them.

After about 40 minutes, he returned, confirming he had found Priyo. My father-in-law focused on completing the formalities quickly. Shreshtha quietly told me about the disturbing conditions: around 25 bodies were left on the floor in a small, closed room without even a fan. The bodies were uncovered and scattered, with limbs intertwined and blood stains everywhere.

I questioned how there could still be fresh blood from bullet wounds inflicted the previous evening. Shreshtha couldn't say for sure, as there was so much blood it was impossible to tell which belonged to whom.

By then, Priyo's friends had arrived. I spoke to a few who were with him during the incident.

They had been at a procession and were walking Medha, another friend, back to her house on Central Road. As they turned from Science Lab onto Green Road and reached the end of Central Road, they heard gunshots. They ran into Central Road, with Priyo at the back of the group.

Suddenly, they looked back and saw Priyo had fallen. The gunfire continued from behind, with the police firing from a corner further back from Lab Aid. When the shooting stopped, they went back and saw that the police had taken Priyo away.

He had been shot in the lower left side of the

back of his head, and there was blood on the pavement at the entrance to

Central Road.

The police had left Priyo's body at the morgue, issuing only an unidentified death certificate citing "gunshot injury." The next steps were to have the body examined by the police from the station where the incident occurred and then sent for autopsy.

However, there was uncertainty about which police station was responsible. It could have been Kalabagan, Dhanmondi, or New Market. Since we hadn't received any news from Dhanmondi or Kalabagan the previous night, I suggested contacting New Market Police Station.

By that time, the curfew had resumed, so Priyo's friends rushed to New Market Police Station with the ambulance.

At the morgue, more bullet-ridden bodies arrived. People filled out registry forms, leaving the stretchers with the bodies under the open sky. Most were young men between 20 and 35 years old.

Their clothes had been removed, likely for examination during the death certificate process. Most wore pants, except for one in a lungi.

I froze when I saw a young boy's body. Fardeen. My school friend. We used to explore the old abandoned building together, searching for mysteries. A moment later, I regained my composure, realizing that after so many years, Fardeen wouldn't look like this teenager. This boy was shorter and thinner than I remembered Fardeen being.

A woman behind me suddenly said, "Can't they shoot at the legs? They're shooting everyone in the chest and stomach." Many people looked at her, but no one answered. I thought of adding, "And in the head too," but decided against it.

The SI arrived, examined the body, and left for a spot inspection to confirm if the case fell under his station's jurisdiction. After confirming, he prepared the report and sent the body for autopsy. It was almost six o'clock by then.

Outside the morgue, there was a shortage of

stretchers. Bodies were brought in and left haphazardly on the floor, covered

only with sheets. Blood stained the floor and walls. The overwhelming stench of

blood, flesh, and phenyl forced me outside, where I stood under a mango tree.

Someone mentioned coffins were available there, and it was best to buy one now before they ran out. Mr. Asgar Ali from Narayanganj was negotiating the price of a coffin. He told me his brother-in-law had been shot in the stomach and died. He ran a chicken shop in Narayanganj and was closing up when a stray bullet pierced his stomach and exited through his chest.

A teenage girl wandered around, holding a form, searching for her father who had disappeared during curfew after going out for a cigarette.

We tried to expedite our post-mortem serial, as we needed to transport the body to Rangpur. The heat was stifling. The mortuary worker, overwhelmed, exclaimed, "Are you crazy? We've had 55 bodies since last night. We're human too."

Finally, the autopsy was done around 10:30 pm. After preparing the body, we left in the ambulance a little after 11. On the way, we stopped to see the blood-stained road in front of Central Road. The marks were stark and disturbing.

The curfew was still on, so we had to hurry back to the vehicle. Everyone got in, except Priyo's friends. They showed no fear or tears, only a quiet determination. They seemed like dispassionate avengers.

Writing this has been difficult. I've struggled to confront this nightmare again. But ultimately, I realized this story is part of our collective memory of this movement. It needs to be documented.

Priyo leaves behind a three-year-old daughter.

She doesn't just call him "dad," she says "my Priyo-dad." It's a tender phrase, as if she's writing love letters to her father with every word.

—-

Translated from Bangla by Faisal Mahmud