The fallacy of separating Mujib from Hasina reeks of fascist apologism

A well-known idiom would best summerize what I am about to say in this article. "The apple doesn't fall far from the tree," which essentially suggests that children often share traits with their parents.

Mahfuz Anam, the editor of the Daily Star, has recently penned a lengthy article addressing the recent cancellation of several national days, many of which are directly linked to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

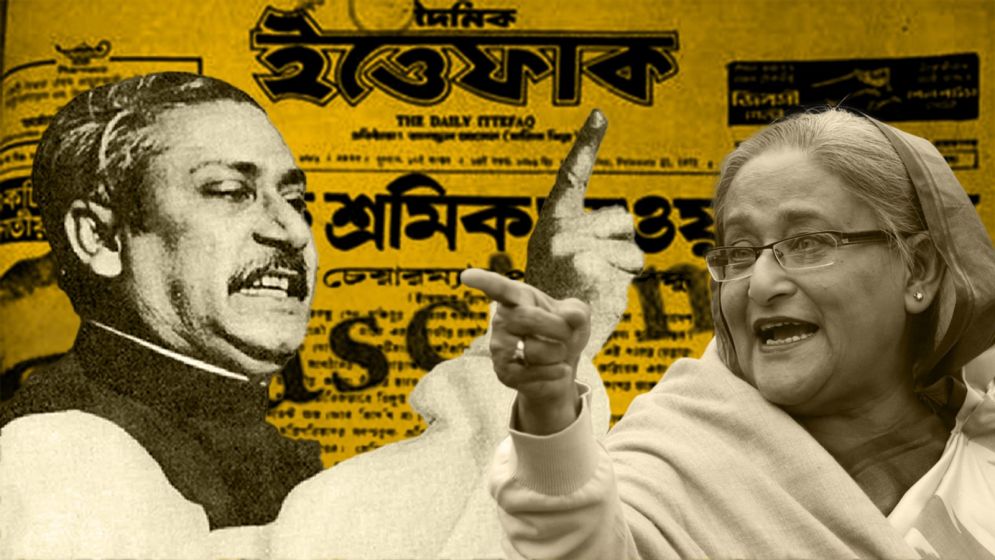

Titled "Don’t Judge Bangabandhu Through Hasina’s Misrule," the article emphasizes that we should not undermine Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s unique place in our history or project the negative aspects of his daughter’s authoritarian rule onto Mujib’s political career up until 1972.

Anam views the cancellation of significant dates like March 7 and August 15 as a direct attack on the history and legacy of our independence movement, which he believes is embodied by Mujib.

He acknowledges that Mujib’s legacy from 1971 to 1975 is controversial but argues for a clear distinction between the legacies of pre-1972 and post-1972 Mujib.

However, he does not explain how to hold post-1972 Mujib accountable without tarnishing his overall image, which remains unaddressed.

This appeal to restore Mujib’s prominence in our national calendar has understandably drawn significant criticism on social media and online opinion platforms, with many individuals offering strong rebuttals to Anam’s arguments.

Rather than reiterate those points, I would like to make two observations regarding the cancellation of national days associated with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

Canceling March 7 and August 15 as national holidays does not erase our nation’s history. Those dates will still exist, and people are free to celebrate or honor them in any way they choose, whether privately or publicly.

March 7 has only been recognized as a national holiday since 2021, so it is difficult to claim that it was erased from public memory for fifty years. Despite the tragedy of August 15, many Bangladeshis feel it does not warrant a national holiday.

Determining historical significance

Our national calendar cannot be dominated by the events of one individual’s life; we are not a one-man nation. There are significant differences among people regarding whether we should recognize a single Father of the Nation or acknowledge a group of historic figures as Founding Fathers.

History is a living process, particularly for a developing country like ours. We are continuously creating history, and sometimes recent events are as significant as those in our past. We cannot limit our historical remembrance to just 1971 and one individual’s life.

Notably, Badruddin Omar, one of our nation’s most respected historians, has stated that the July Uprising of 2024 was the most spontaneous and widely participated mass uprising in our history.

Given his extensive experience with various uprisings and movements, his perspective carries weight. We need to commemorate and celebrate the July Uprising, and new national days should naturally replace the old ones on our calendar.

Anam's primary argument is that Sheikh Mujib's legacy should not be overshadowed by Sheikh Hasina’s recent regime. To acknowledge the truly horrific nature of Hasina’s rule, he uses many strong and provocative descriptors.

He characterizes her regime as "fundamentally flawed, undemocratic, anti-people, corrupt, power-hungry, intolerant, and fascistic." In another instance, he states that the manipulated elections of 2014, 2018, and 2024 transformed the Awami League into a fascist party.

The frequent use of such adjectives suggests some curious mental gymnastics on Anam’s part.

If Sheikh Hasina's regime was indeed fascistic and the July Uprising was a genuine mass revolt, why would Anam expect those who overthrew such a regime to respect and uphold its main symbols?

When has this ever occurred in modern history? When have people freed from a fascist regime, after a bloody struggle, kept the icons, monuments, and symbols that the regime used to justify and sustain its undemocratic rule? We all know how symbols of fallen fascist regimes are typically treated.

Understanding the fascist route of

Awami regimes

Anam's acknowledgment of Hasina's regime as fascist brings us to a crucial point. All students of politics understand that fascist regimes and political parties do not emerge in isolation; they have historical roots within the nations where they arise. What is the historical background of Sheikh Hasina’s fascist regime?

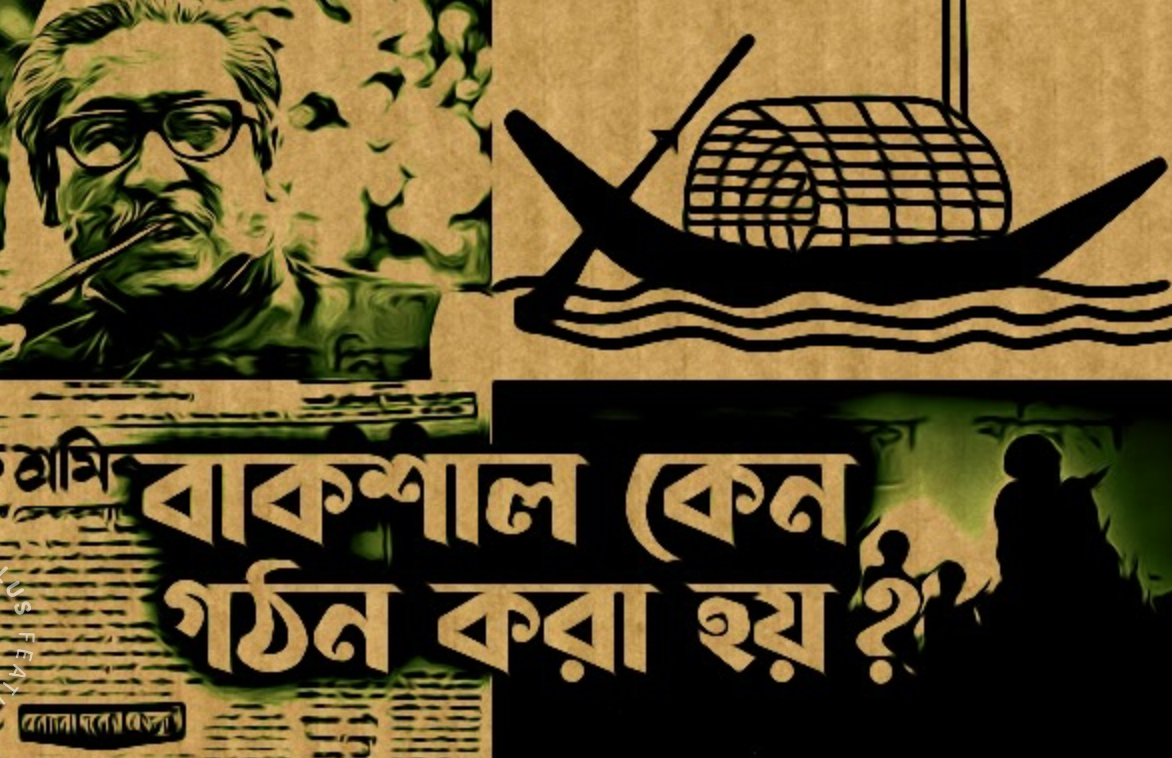

Many would argue that Hasina's regime is closely related to the Sheikh Mujib government of 1972-1975.

The elements of a “fundamentally flawed, undemocratic, anti-people, corrupt, power-hungry, intolerant, and fascistic” regime—terms Anam himself used to describe Hasina’s government—were all present during the post-independence era.

In the first national election of independent Bangladesh, held on March 7, 1973, the Awami League won 293 out of 300 seats. Given that there were no significant national opposition parties, the Awami League was virtually guaranteed an absolute majority.

Yet, despite this certainty, the ruling party resorted to blatant and extensive vote rigging in every constituency, unable to tolerate the possibility of any opposition expressing itself at the ballot box.

Sheikh Mujib was elected unopposed, as Awami thugs intimidated anyone who even considered running against him. The idea that someone could stand as an opposition candidate alongside Mujib was simply unthinkable.

The Mujib regime was marked by a highly centralized concentration of political power within a tight inner circle primarily composed of his relatives and close associates. Every detail of governance was managed by this select group, with parliament serving merely as a rubber stamp for policies and legislation.

Draconian laws, such as the Special Power Act, and partisan forces like the Rakkhi Bahini operated with impunity to suppress any opposition. By 1974, over 30,000 political prisoners filled the jails to capacity.

Do these elements sound strikingly familiar and disturbingly close to our current reality? All of this transpired even before BAKSAL was declared. When examining the personal and political conduct of both Mujib and his daughter, it's evident that she has not strayed far from her father’s legacy.

Numerous anecdotes and accounts from that era highlight the delusions of grandeur and the God complex that Mujib developed after 1972.

Interviews conducted by both foreign and domestic journalists reveal that Mujib viewed himself as the embodiment of the nation. He echoed Louis XIV's famous declaration, "L'État, c'est moi" (the state, it’s me).

Stories about Tajuddin Ahmed, who was our true national leader during the 1971 war and Mujib’s nominal second-in-command from 1972 to 1975, illustrate how Mujib treated governance as his personal domain, imposing his temperament on the administration.

He often threatened to resign, but Tajuddin, well-acquainted with Mujib’s personality, dismissed these outbursts with ease.

When BAKSAL was announced, Tajuddin famously cautioned Mujib that he was permanently closing the door on a peaceful resolution to his regime.

In August 1975, just before the tragic events of the 15th, there were political maneuvers underway to declare Mujib a president for life.

Given these historical echoes, it’s surprising that Anam claims we shouldn’t judge "Bangabandhu through Hasina’s misrule."

Sheikh Hasina has merely sought to restore the family legacy, which has consistently aimed to turn the nation of Bangladesh into the personal property of the Sheikh family.

—--

Shafiqur Rahman is a part-time Political Economist and a full-time writer-activist. He divides his months in the year between Vancouver, Canada, and Dhaka, Bangladesh