July 2024 is not the antithesis of December 1971 but its continuation

In the wake of the July Uprising, a fierce ideological battle has erupted among the victors of the movement, each vying to claim the spirit and direction of the national revolt against the Hasina regime.

From the opposition BNP and Jamaat to student activists, radical leftists, and vocal YouTube commentators, competing factions are jockeying to define the uprising on their own terms.

Amidst this cacophony of voices, one narrative is gaining traction: that the July Uprising represents a fundamental repudiation of the values and goals of Bangladesh’s 1971 Liberation War.

This argument is predominantly championed by a faction that remains deeply aggrieved by the country’s separation from Pakistan in 1971.

These voices, many of whom have gained a significant presence online, are often labeled "East Pakistanis" by their critics.

Though their influence appears formidable in the virtual world, their actual political strength—particularly in the realm of traditional, offline politics—remains uncertain, and may only be fully understood through the lens of a free and fair election.

The “East Pakistani” contingent found its initial affirmation in the July Uprising when students at Dhaka University, responding to Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s dismissal of the quota movement activists as descendants of 1971 collaborators, raised the slogan: “Tumi ke? Ami ke? Rajakar! Rajakar!” (Who are you? Who am I? Collaborator! Collaborator!).

For many, this moment was an unequivocal symbol of the failure of the Hasina regime’s decades-long effort to reshape the collective memory of the nation’s founding. Yet, for the “East Pakistanis,” it signaled the younger generation’s deliberate rejection of the 1971 legacy.

Their sense of vindication deepened as the social ostracism of regime apologists, such as the celebrated writer Zafar Iqbal, gained traction during the movement.

For “East Pakistanis,” this growing boycott reflected a broader disavowal of the nation’s foundational narrative—one that tied the country’s identity and legitimacy to the 1971 war and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s leadership.

The culmination of this feeling came on the afternoon of August 5, when statues of Sheikh Mujib were torn down across the country and his Dhanmondi 32 residence was set ablaze.

The significance of these actions is hotly contested. Many see them as a natural, cathartic release after fifteen years of forced veneration of Mujib by the state—an inevitable consequence of any mass uprising in history, which often includes the dismantling of symbols associated with a fallen regime.

However, for the “East Pakistanis,” the destruction of Mujib’s statues was not just a rejection of the political elite that had upheld his legacy, but a symbolic denouncement of everything the late leader represented, including Bangladesh’s war for independence.

The final twist in this narrative comes from the growing hostility of the Indian government and media towards the post-Awami regime in Bangladesh.

India, as Bangladesh’s principal ally during the Liberation War, played a decisive role in the nation’s birth in 1971.

For the “East Pakistanis,” India’s apparent antipathy toward the uprisings and the new Bangladesh government is nothing short of confirmation that the events of July 2024 stand in direct opposition to the spirit of December 1971.

As Bangladesh continues to navigate its post-uprising trajectory, the battle over its historical identity is far from settled.

While the “East Pakistanis” may see the events of July as a repudiation of the nation’s founding, many others view it as the inevitable clash of generations—one that reflects a growing disillusionment with the state’s narrative.

Only time will tell which of these competing visions will come to define the future of Bangladesh.

Is the divide between 2024

and 1971 as stark as it seems?

Do the contrasts between 2024 and 1971 truly place these two moments in opposition within our national history?

The answer, quite definitively, is no. In fact, there exists a deep and fundamental continuity between 1971, 2024, and, I would argue, even 1947.

These pivotal events are not isolated chapters, but part of a unified narrative, with 2024 simply representing a continuation of the struggle that began in 1971.

Ironically, the supporters of the fallen regime view the July Uprising through a lens similar to that of the "East Pakistanis," seeing it as a rejection of the 1971 struggle.

Before the seismic events of August 5th turned their world upside down, the Awami League was vociferous in condemning the uprising as a naked power grab by anti-liberation forces.

Since that day of upheaval, the Awami camp has largely retreated into internal circles, seeking solace among themselves.

Yet, occasional leaks suggest that they continue to cling to this narrative—one where the uprising is seen as a betrayal of 1971. It’s a curious case of the "Horseshoe Theory," where ideologically opposing factions find themselves meeting at the same point, united by a shared narrative of the past.

There's no denying that the narrative of 1971 was, for much of Hasina's tenure, used as a primary ideological support for her authoritarian regime.

Alongside the cult of Mujib and the mantra of "development over democracy," this narrative became one of the key pillars of the regime’s legitimacy.

An entire state-sponsored industry, costing the nation billions of takas annually, was built to propagate these ideological tenets—not just within Bangladesh but across the globe.

As with any form of pure propaganda, these tools often relied on distortions, exaggerations, and outright falsehoods. The 1971 narrative was no exception.

We are all familiar with the many excesses surrounding the portrayal of 1971. The roles of key figures from that time were either downplayed, inflated, or outright slandered.

The list of "freedom fighters" grew exponentially, creating a partisan force within the government through quotas.

The number of deaths during the war became a sacred, untouchable figure, while the massacres of Bihari people—before, during, and after the war—were systematically erased from public discourse.

Every December 14th, the ritual lamentation over the intellectuals lost in the war became a routine affair, accompanied by hollow promises to compile a list of these martyrs—a task that, despite fifteen years of commemorations, never materialized, likely because the truth was too inconvenient to face.

It is essential that we confront how the Awami League exploited 1971 and Mujib as ideological tools to justify its rule.

This is a necessary part of our reckoning. The regime, in effect, imposed a quasi-religious ideology upon the nation, rooted in 1971 and the figure of Mujib.

And like any religion, this political system left no room for dissent. Questions about the legacy of 1971 and Mujib were not tolerated; only hagiographies and state-sponsored propaganda found a place in the public sphere.

The regime actively suppressed academic inquiry and public debate on these subjects through draconian laws, physical intimidation, and societal pressure.

Yet, as the July Uprising and the subsequent opening of public space have clearly shown, the fifteen years of state-sponsored ideological indoctrination around 1971 and Mujib have failed spectacularly.

The carefully constructed mythos of the past has crumbled under the weight of genuine public discourse, revealing the fragile nature of the regime’s power.

The July Uprising was not just a political revolt; it was a repudiation of the false narrative that has held sway over Bangladesh for decades.

The failed cause of

indoctrination

The reasons behind the failure of this decade-and-a-half-long, multi-billion-dollar national indoctrination remain unclear.

While social and anthropological research may offer some insight, we can reasonably speculate that a significant part of the mystery lies in the cognitive dissonance caused by the Awami League’s propaganda and the reality of its governance.

The gap between the regime’s idealized narrative of 1971 and Mujib and its public behavior was simply too wide to be ignored, even by those with the dimmest awareness.

The regime’s brazen acts of looting, murder, deceit, domination, and corruption stood in stark contrast to the sanctified version of 1971 and Mujib they sought to promote.

People instinctively recognized that such dishonesty could not align with the true spirit of either the 1971 Liberation War or Mujib’s legacy.

For over fifty years, the Awami League has distorted the historical record to suit its own ends, offering a self-serving interpretation of the 1971 struggle.

Free and open research and debate might eventually offer important revelations, but interpretations of monumental historical events can never be fully objective.

The sheer scale, complexity, and long-lasting impact of these events make it impossible to arrive at a singular, universally accepted narrative. Even events thousands of years old continue to be debated.

The same is true for 1971. Some see it as the negation of the Two-Nation Theory; others view it as a triumph of Bengali nationalism, or the result of India's meticulous political maneuvering; still others interpret it as a victory of Bengali Muslims over Pakistani Muslims.

Each interpretation contains elements of truth, but none are entirely correct or completely wrong.

Most patriotic Bangladeshis would likely agree that the core of the 1971 Liberation War was the people’s desire to be free from the domination of West Pakistan.

The Six-Point Movement of 1966 also centered on freedom from political and economic oppression, and 1971 can be understood as the continuation of that struggle.

The people of this land were deeply aggrieved by the overt racism and chauvinism they suffered at the hands of the West Pakistani military and political elite.

The speeches, songs, poems, and testimonies from 1971 overwhelmingly reflect a single, unifying theme: the desire to end West Pakistani domination.

Even in 1947, when the partition of Bengal was widely supported, the central motivation was freedom from the dominance of Calcutta-based political, business, and cultural elites.

The 1947 partition laid the territorial foundation for modern Bangladesh, and our national identity has remained deeply rooted in that territory ever since.

The fight for freedom in July

2024

The July Uprising of 2024 will, undoubtedly, have many interpretations. However, one central theme seems clear: the people’s desire to be free from domestic domination.

The Hasina regime stands as the most oppressive and tyrannical in Bangladesh’s history.

Politically, it exceeded even the Pakistani military dictatorship of the 1960s and the British colonial rule of the 1920s and 1930s, a period when local democratic movements in India were allowed to emerge and take their initial steps.

As revealed in one of her leaked phone calls from July, Sheikh Hasina referred to the country as her "baper desh" (family property), making it clear that she felt entitled to do as she pleased without anyone standing in her way.

This sense of entitlement, coupled with the regime’s unchecked corruption and authoritarian rule, has provoked a deep and growing resistance.

The July 2024 Uprising was, above all, a fight for freedom from the grip of a domestic, occupation-like regime.

It began with the first student protests at Dhaka University and was later marked by the iconic martyrdom of heroes such as Abu Sayeed, Mir Mugdho, and Wasim.

The brave students and youth from private universities, schools, colleges, and madrassahs who took to the streets—defying bullets and machetes—were fueled by a singular vision: freedom from oppression and domination.

Ordinary people from every neighborhood joined the protests, adding their voices to the growing movement. Throughout it all, the rallying cry was clear: resistance to tyranny.

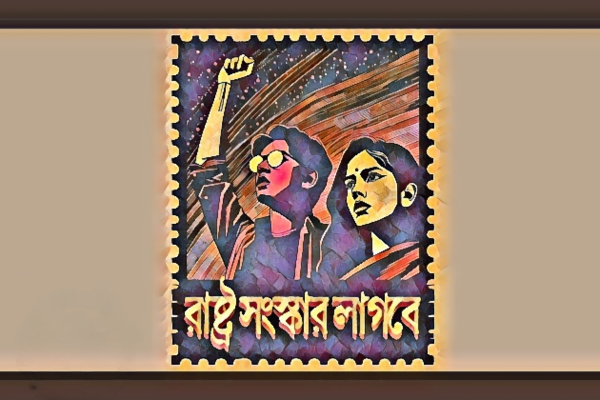

A striking feature of the July Uprising was the way many of its slogans, graffiti, songs, and social media memes drew direct inspiration from the 1971 Liberation War.

The youth of the movement saw themselves as heirs to the freedom fighters of 1971, continuing the struggle for a sovereign and just Bangladesh.

Since 1947, Bangladeshis have forged a distinct sense of nationhood, and nearly eighty years later, that identity remains firmly defined.

Ethnicity, religion, language, and civic values all play a role in shaping our national character. While ethnicity and religion can sometimes create divisions, especially in the modern era, language and civic values such as democracy, freedom, and social welfare serve as more inclusive forces.

These values bind us together, creating a cohesive sense of community across our diverse society.

For the past eight decades, the collective struggle of Bangladesh’s people has been driven by the desire to free themselves from various forms of domination—whether it came from Calcutta, West Pakistan, domestic powers like the Awami League, or even external influences like India.

Each time, our people have risen in resistance, driven by the fundamental civic value of freedom.

The events of 1947, 1971, and 2024 are all monumental milestones in our nation’s history. However, 1971 remains the defining moment, as it was the year Bangladesh was born.

As long as Bangladesh remains a sovereign nation, the glory of 1971 will continue to shine as our foundational triumph.

—-

Shafiqur Rahman is a part-time political economist and a full time writer-activist. He divides his months in the year between vancouver, Canada, and Dhaka, Bangladesh.