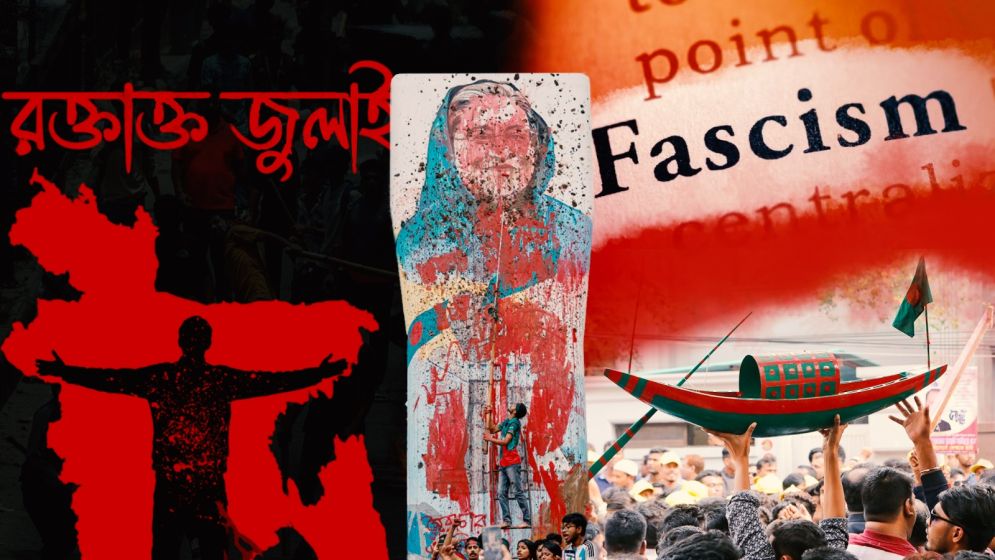

The practical path to dissolving a “fascist” party like Awami League

In Bangladesh, as in many parts of the world, there is a tendency among thinkers and political leaders to reinvent the wheel when it comes to addressing deep-rooted political challenges.

A case in point: the question of how to dissolve a fascist party.

The truth is, dismantling such a party is hardly a novel or complex undertaking. In fact, it’s not rocket science. Nor does it require the kind of extreme, genocidal violence that history has unfortunately seen.

At its core, the process is simple: You encourage the absorption of the party’s members and supporters into other, more democratic political movements. It’s just simple political pragmatism.

The real challenge, however, arises when dealing with the dangerous ideology that fuels a fascist party. While the operational mechanics of dissolving the party are straightforward, eradicating the ideology is a far trickier business.

By definition, a fascist party thrives on an ideology that resonates with a significant segment of the population.

The solution, then, is to ban the ideology itself, outlaw its symbols, and ensure that the public is educated in a way that facilitates the rehabilitation of those who may have been drawn to its poisonous doctrines.

It’s about helping people leave behind the fascist past they’ve been indoctrinated into and reintegrating them into a more inclusive society.

Of course, that doesn’t address the more pressing issue: the crimes committed by the party’s members and supporters.

Those crimes—whether they involve enforced disappearances, judicial killings, or outright massacres—cannot be swept under the rug.

There are courts to prosecute the guilty. Special tribunals could be established. Alternatively, a truth and reconciliation process might offer a pathway to healing.

But this latter option would be untenable without justice. Accountability is crucial, and those responsible for crimes against humanity must be brought to trial.

In sum, dissolving a fascist party involves a few simple steps: absorbing non-criminal members into other political organizations, outlawing the ideology and its symbols, and holding accountable those who have perpetrated crimes.

It’s not a question of eradicating an idea—fascist ideology, like any dangerous belief system, can evolve and adapt, finding new symbols and expressions.

But a party, with its leaders and structures, is a tangible entity. It can be destroyed.

-67a332413498c.png)

The key to dismantling fascism:

Absorbing, not exiling

Fascist parties are not ideas—they are organizations, and organizations can be dismantled.

The key is to remove the architects of violence, prosecute the criminal leaders, and dismantle the networks that sustain them. It may not be easy, but it is entirely feasible. What’s required is the political will to make it happen.

Banning the symbols and ideology of a fascist movement is not just a symbolic gesture—it’s a crucial step in preventing the ideology from rebranding itself.

Ideology and symbols gain power through a process of sedimentation, a gradual buildup of meaning over time.

That kind of sedimentation doesn’t happen overnight, and for fascism to reinvent its symbols, it would need to overcome significant obstacles.

In short, simply outlawing its symbols hampers any attempt to breathe new life into its dangerous doctrines.

But this alone isn’t enough. The real challenge lies in absorbing the rank-and-file supporters of fascism, those who aren’t directly complicit in criminal acts but have been swept up in the movement’s appeal.

If these individuals are reintegrated into society as equal and dignified members, they will have little incentive to return to the fascist cause. Rehabilitation, not exile, is the antidote to extremism.

Without this effort, a fascist party—no matter how many laws are passed—will never truly disappear. History teaches us that.

A party, after all, is only as powerful as the people who support it. And if you fail to offer an alternative to those people, they will find refuge in the very movement you’re trying to dismantle.

This is not just true of fascist parties, but of any political group: without absorption and rehabilitation, the roots of opposition remain firmly planted.

Bangladesh’s past offers a cautionary tale. The fascist Awami League government, for all its attempts to ban Jamaat-e-Islami and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), ultimately failed to crush these parties because it made no effort to absorb their members.

Instead, it created a political apartheid—criminalizing millions and closing the door on any meaningful integration.

Had the Awami regime embraced a more inclusive approach, welcoming people from all political backgrounds into the fold, it might have been able to neutralize its opposition more effectively.

Instead, the government under Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has failed precisely in this area. By focusing on marginalization and exclusion, Hasina's regime has inadvertently allowed the very parties it aims to dismantle to endure—thanks largely to the oppressive system of exclusion her government has put in place.

By denying people any meaningful place within the political ecosystem, it has forced many into the arms of BNP and Jamaat, keeping the opposition alive and kicking.

This system of apartheid, rather than snuffing out opposition, has helped perpetuate it.

-67a33266cb324.png)

The dynamics of dissolving a fascist

party: Interests over ideology

Too often, thinkers place too much emphasis on ideology as the primary driver of political movements. Yes, ideology matters—but it’s not the only factor.

People’s beliefs evolve, often dramatically, as they interact with others and as their personal circumstances shift. Ideology is fluid; it doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It changes based on context and the experiences people go through.

By offering a path of reintegration, we give people the chance to redefine their beliefs and align themselves with the broader community, making it far less likely they’ll return to the extremist ideologies they once embraced.

In the end, the key to dissolving any fascist party is not merely banning its symbols or outlawing its ideology.

It’s about building a more inclusive society—one where even those who once espoused hate can find a dignified place. Only then can we truly prevent the forces of extremism from reappearing.

Consider the coordinators of the July Revolution who distanced themselves from the terrorist student wing of Hasina’s party.

While they may still hold some ideological affinity with Hasina’s fascist agenda, the one thing we can be sure of is that they will never allow that kind of party to resurface. It simply isn’t in their interest anymore.

Branded as traitors by Hasina’s regime, they know full well that, should she make a political comeback, they would be the first targets of her revenge.

In this case, their shift in allegiance isn’t just ideological—it’s driven by pragmatic self-interest. Their survival now depends on distancing themselves from the very party they once supported, and this shift in interest has fundamentally reshaped their political views.

They have no desire to see the fascist party revived because doing so would put their own safety and political future at risk.

Dissolving a fascist party, in its simplest form, is about erasing the interests that sustain it. If people no longer have any stake in the survival or revival of the party, then the party itself will lose its foothold.

This dynamic is something the political opposition in Bangladesh needs to grapple with. BNP, Jamaat, and the emerging student-led party are under significant pressure—both from the public and from within their own ranks—not to absorb any members or supporters from Hasina’s party.

Yet, it is crucial for political parties and public intellectuals alike to help the public understand that refusing to integrate those who were once part of the fascist regime only strengthens the very forces they seek to dismantle.

In other words, failing to absorb ex-fascists, or at least offer them a dignified place within society, creates a vacuum of disenfranchised individuals who may one day turn back to the fascist party they know all too well.

The key to dismantling fascism lies not in exclusion, but in reintegration.

—

Md Ashraf Aziz Ishrak Fahim is a graduate student of Contemporary Islamic Studies at Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Qatar. Reach him at mdfa48907@hbku.edu.qa