In a turbulent Bangladesh, Yunus still remains the lone stabilizing force…. here’s why

By any measure, it's an extraordinary claim: that the fate of a nation– its international legitimacy, its economic survival, even its fragile civil peace– rests on a single figure.

But to understand why Bangladesh may be spiraling toward a political legitimacy crisis, one must confront an uncomfortable truth: we still need Professor Muhammad Yunus.

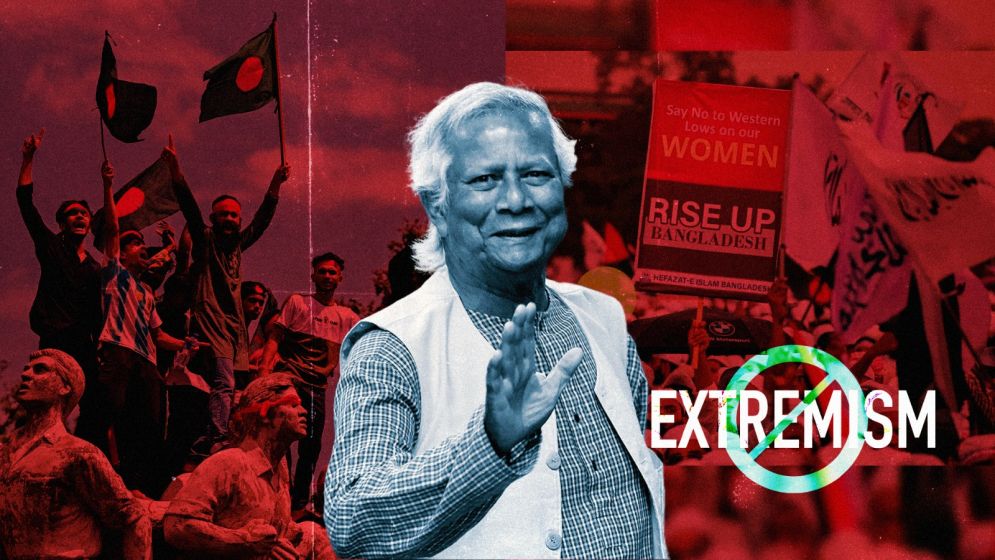

We need him because, in the eyes of the global order, he is the last acceptable face of a country otherwise typecast as a potential breeding ground for extremism.

This isn’t hyperbole. It is the tragic political geometry of the post-9/11 world– a world where Muslim-majority nations are often seen as security threats-in-waiting. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the sunset of the Eisenhower Doctrine, Islam has been steadily othered into a global boogeyman.

And in the years since 2001, the stereotype has ossified: every Muslim child is seen, implicitly or explicitly, as a future radical. Bangladesh is no exception.

The Bangladeshi Nationalist Party (BNP), through its bungled response to Islamist militancy during its 2001–06 tenure– and a faction’s naked opportunism in flirting with extremists– helped cement that image. In the vacuum of global trust that followed, the Awami League seized the reins, buoyed by a simple but potent promise to the West: we will keep the terrorists at bay.

But that promise came with a price. It required a guarantor– and India willingly stepped in.

Delhi offered the world its assurance that Sheikh Hasina’s regime would keep Bangladesh stable, secular, and open for business. In return, India extracted its pound of flesh: lopsided trade deals, strategic concessions, and the carte blanche imposition of its geopolitical will.

Inside Bangladesh, the Awami League fused the machinery of the military, bureaucracy, crony capitalism, and its student wing into a kleptocratic engine. State institutions were gutted, the banking system hollowed out, and a sprawling apparatus of phantom finance shackled future generations to debts they never incurred.

Behind this plunder was the ironclad shield of India’s legitimacy.

That shield is now cracking. In the post-July political landscape, India is attempting to reassert its central role– but the West is skeptical. Which brings us back to Professor Yunus.

Yunus, the architect of microfinance and the global darling of neoliberal aid models, now serves as Bangladesh’s last passport to Western credibility. He represents everything the post-9/11 global order demands from a Muslim-majority nation: pacifism, capitalism, and a strong disinterest in theology.

His continued presence, even as a symbolic figure, reassures donors and diplomats alike that Bangladesh will not veer off into radicalism.

And the irony is almost too much to bear: Islamists, who long derided Yunus as a secular stooge, are now lining up to endorse him. Even firebrand Salafi figures, who once viewed him as the embodiment of Western infiltration, have begun cautiously supporting his role.

Why? Because in a country perennially one narrative shift away from being labeled a pariah state, Yunus grants immunity– not just to secular liberals, but now, bizarrely, to the Islamists themselves.

A surreal reality

It is a surreal coalition held together by desperation, not ideology.

The very factions that once dismissed Yunus are now banking on his international brand to shield them from scrutiny. And in that strange, precarious alliance, we see the true tragedy of Bangladesh's politics: a nation whose sovereignty now hinges not on its institutions or constitution, but on the reputation of one man in the eyes of Washington, Brussels, and Delhi.

If that doesn’t terrify you, it should.

Inside the current regime, governance has devolved into a farce. A cohort of petty opportunists–more interested in skimming profits off cattle markets like Gabtoli than managing a functional state–now sets the tone for national policy.

They are racketeers in bureaucrats’ clothing. Elections, for them, represent a threat, not a civic duty. And so, predictably, they resist any timeline that might bring accountability to their doorstep.

On the other side, Islamist factions like Jamaat, fully aware of their diminishing electoral relevance, have shifted strategy. They are no longer trying to win at the ballot box. They are embedding operatives, flexing muscle, and scrambling for strategic spoils–bureaucratic posts, contracts, informal tax regimes–that can sustain their networks regardless of who nominally rules.

India, meanwhile, sees an opening. New Delhi wants a swift election, but only on its terms–and those terms include the removal of Dr Yunus. The calculation is coldly transactional: no one in the BNP can offer the anti-terrorism assurances that keep Western donors calm and foreign investors docile.

Once Yunus is gone, India assumes the international community will have no choice but to restore its previous role as Bangladesh’s de facto external guarantor. The BNP knows this and is quietly building an anti-Yunus narrative to preemptively shape the battlefield.

But here’s the trap: should the BNP take power, it will walk into a buzzsaw. India, along with its loyal nodes inside Bangladesh’s media and intelligence apparatus, will begin the slow, methodical erosion of the BNP’s credibility.

Not because the BNP is uniquely corrupt or incompetent–but because, unlike the Awami League, it cannot operate the machinery of extraction with the same ruthless efficiency.

Let’s be clear. The Awami League has perfected a model of governance that transforms state terror into capital. Through systematic fear, it has turned the sweat and muscle of migrant laborers and garment workers into fungible profit, melting their bodies down into global supply chains like so much economic jelly.

India knows it. The military knows it. The bureaucracy knows it. They’re all hooked on Awami League-style state capitalism, even as they grumble about the decay it breeds.

The truth is, even those inside the state who whisper about change can’t quit the Awami League. Like Kalidas’s exiled lover in Meghdoot, they pine for the monsoon of stolen prosperity, even as the system they defend hollows out before their eyes.

And in the middle of this chaos stands Professor Yunus–a Nobel laureate turned reluctant firewall. For all the speculation, it’s hard to detect any selfish motive driving him.

Legal relief, tax leniency, regulatory adjustments–these are crumbs he could have easily negotiated under a different government. If he remains, it’s not because it profits him. It’s because he still believes, against all reason, in the idea of Bangladesh.

But belief alone is no longer enough. Like a nuclear deterrent in a Cold War farce, Yunus’s position has become paradoxical.

In Yes, Prime Minister, there's an episode on the absurdity of deterrence: when your only weapon is a doomsday device, you can’t use it for minor threats. If you bomb Russia for entering France, you end the world. If you don’t bomb, your deterrent is exposed as useless.

Yunus faces the same conundrum. His only weapon is resignation. But once you threaten to resign, and then don’t, the threat begins to erode. His presence was supposed to reassure. Now, the overuse of his symbolic power is starting to show diminishing returns.

He was placed atop the state as a scarecrow—to deter, not to decide. But even scarecrows stop scaring once the crows realize they're just straw.

And the crows are circling.

The way out

And yet, for all the dysfunction, there remains a narrow path out. Professor Yunus and the BNP–unlikely allies in a fractured landscape–still have the means to pull Bangladesh back from the brink.

Yunus, for his part, must come to terms with a basic fact: this regime, despite the puffed-up bravado of its cronies, is running on borrowed time. The clock is ticking. The more constructive move now is negotiation.

If Yunus truly believes in the idea of a democratic Bangladesh, he must recognize that brokering a peaceful transfer of power is not just desirable, it is necessary.

But the BNP, too, must undergo a political reckoning. Bangladesh is not the same country it was in 2006. Sixteen years of Sheikh Hasina’s authoritarian consolidation have rewired the political circuitry. There is no longer a single hegemonic narrative.

What now exists is something closer to a chaotic marketplace of power–a place where ideology, muscle, and media compete in a near-deregulated political economy.

In this new environment, the old tools are obsolete. You can no longer stabilize politics by simply rounding up "40 goons and 400 thugs." Nor can the public be pacified with theatrical mayoral trials or symbolic crackdowns.

The binary has sharpened: either Bangladesh slides into a fully militarized authoritarian state in the Awami League mold–a path the BNP cannot walk, even if it tried–or it must begin building a functional, pluralistic democracy.

And the BNP cannot copy the Awami League’s playbook. It lacks the ideological extremism required to demonize the majority of the population into submission. It cannot afford to alienate global powers with reckless overreach, nor can it blindly trust–or confront–India without consequence.

The party must learn to govern with restraint, to navigate both domestic sentiment and international expectations. In this recalibration, Yunus and his network–globally respected, institutionally savvy, and ideologically moderate–could be valuable allies, if not indispensable ones.

But this goes beyond political maneuvering. There is a deeper sickness that must be confronted: the international dehumanization of Bangladeshis.

The very concept of secular "guarantors" is rooted in a grim global assumption–that Muslim-majority countries cannot be trusted unless someone respectable stands between them and the world.

To dismantle this colonial logic, the country must first fix what gives that narrative fuel: mob violence, misogynistic extremism, and systemic impunity. These aren’t just law enforcement issues. They are existential threats to our sovereignty.

None of this will matter, however, if our politics remains trapped in the tyranny of the short term.

The country’s leaders–on all sides–must learn to think in decades, not cycles. Bangladesh’s survival will not be secured by the next verdict, election, or press conference, but by a strategic vision that outlasts the news cycle.

It will require courage. Restraint. Imagination. And above all, a rare thing in our politics: goodwill.

We could use an awakening of that right now.

—

Mikail Hossain is a researcher and analyst