Democracy is not a temple of order. It’s a marketplace of uncertainty–and at its healthiest, it’s chaotic.

No matter how often we dress it up in the language of ideals, democracy remains, at its core, a high-stakes popularity contest. The electorate–often passionate, frequently inconsistent, and rarely rational–holds the power to steer a nation’s future.

That power is both a gift and a gamble. We entrust it to the masses not because they always choose wisely, but because the alternative is far worse.

Let’s not kid ourselves: democracies don’t always yield efficient or responsive governments. They frustrate. They delay. They often elevate the loudest voices over the most qualified ones.

Yes, the will of the people is not always synonymous with good governance. But it remains the only system where, if everyone plays by the rules, those in power can be peacefully replaced.

That one mechanism–the ability to fire your leaders without bloodshed–is what makes democracy worth the noise.

And yet, in so many political conversations today–particularly in countries teetering between autocracy and reform–there’s a misplaced obsession with “stability.” A yearning for predictable outcomes. As if the presence of electoral turbulence is some fatal flaw in the system.

It isn’t. That turbulence is the system working.

You cannot have democratic outcomes and permanent stability. Those are competing ideals. Uncertainty is not a bug–it’s a design feature. And ironically, the form of government that guarantees the most stability is not a democracy at all. It’s an autocracy in disguise.

That’s the trade-off too many seem unwilling to acknowledge. A stable democracy is, by definition, a contradiction in terms.

What we get instead is a system in constant flux: governments rise and fall, mandates are earned and revoked, and political coalitions shift in ways that can unsettle even the most seasoned observer.

This is democracy in motion.

Fear of uncertainty

But instead of embracing that motion, we fear it.

Political reform discourse often skirts around the system’s built-in volatility, clinging to fantasies of orderly transitions and smooth governance, as though democracy were a conveyor belt, not a contested battleground.

Here’s the truth: we need to stop pretending every election is sacred, that each resulting government must be treated as the final product of national destiny. We have to understand that democracy is a recurring process of accountability and correction–of collective trial and inevitable error.

If anything, the obsession with “protecting” governments or turning every election into an existential showdown only infantilizes the electorate. It suggests they cannot be trusted with disappointment–or with change.

We must grow out of that mindset. Democracy is not here to give us comfort. It is here to give us choice, and with choice comes unpredictability. The sooner we accept that, the closer we get to becoming a mature political society.

The fact is, the next election isn’t the last one that matters. And the government it produces isn’t the one that needs protecting. What needs protecting–and embracing–is the messy, imperfect, beautifully unstable process itself.

Let’s however first dispense with the fantasy that stability guarantees success.

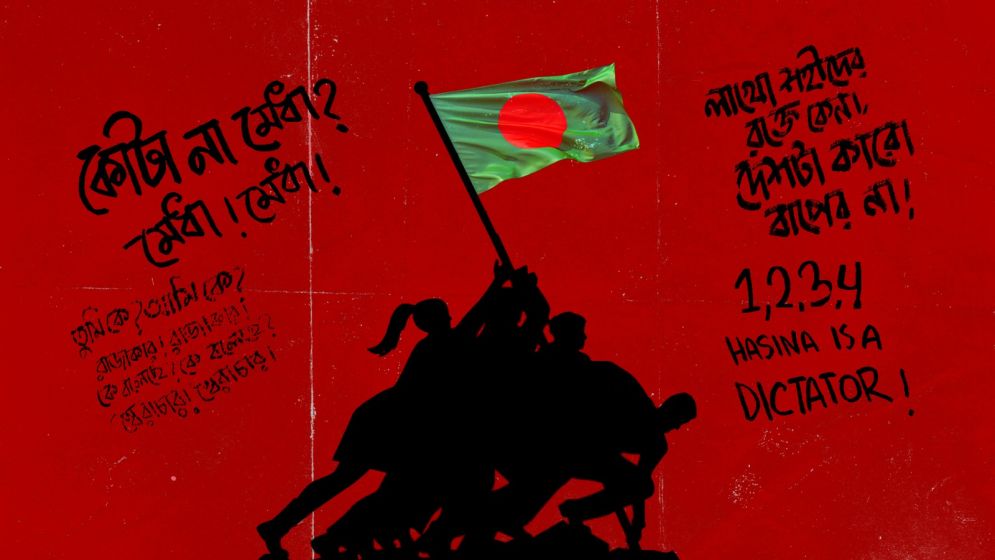

Bangladesh has had its fair share of “stable” governments–administrations with overwhelming parliamentary majorities, little opposition, and all the structural power they could ask for.

At least twice–three times if you count 1973, and six if you count Sheikh Hasina’s last three engineered landslides–the government enjoyed two-thirds control.

And yet, for all that stability, what did we get? Unchecked power. Corrosion of institutions. A deepening democratic deficit.

Because stability without accountability is

just authoritarianism with better branding.

Understanding the beauty of democracy

What the “stability-first” crowd continues to ignore is that legitimacy in a democracy isn’t something you inherit through a rigged mandate or secure through suppression–it’s something you earn through performance.

If you want stable governance, deliver good governance. Full stop.

The real challenge before us is how to construct a political system in which power is meaningfully distributed and restrained.

Power that flows through a functioning legislature. Through an empowered judiciary. Through a media that can report without fear. Through voters who know they can change the game, not just watch it.

Stability, when it exists, should be a byproduct of that balance–not a precondition enforced by silencing dissent or gaming the system.

And if the resulting government looks “unstable”? If it struggles to pass legislation, or keep a coalition together, or respond to crises without imploding? Then maybe–just maybe–that instability is revealing something worth paying attention to.

The burden, in that case, doesn’t fall on the democratic framework. It falls on the political actors operating within it. If a ruling coalition can’t govern, the problem isn’t the system–it’s the players.

Democracy is supposed to test them. Their ability to make deals, build consensus, and navigate complexity should not be bypassed in the name of smooth sailing.

That’s the whole point of a representative system: to force negotiation, not to rubber-stamp domination.

If our politicians are rattled by a little friction, maybe they’re in the wrong business. Because in a democracy worth the name, power is earned, not installed, and stability is never guaranteed, only deserved.

—

Nayel Rahman is a political analyst