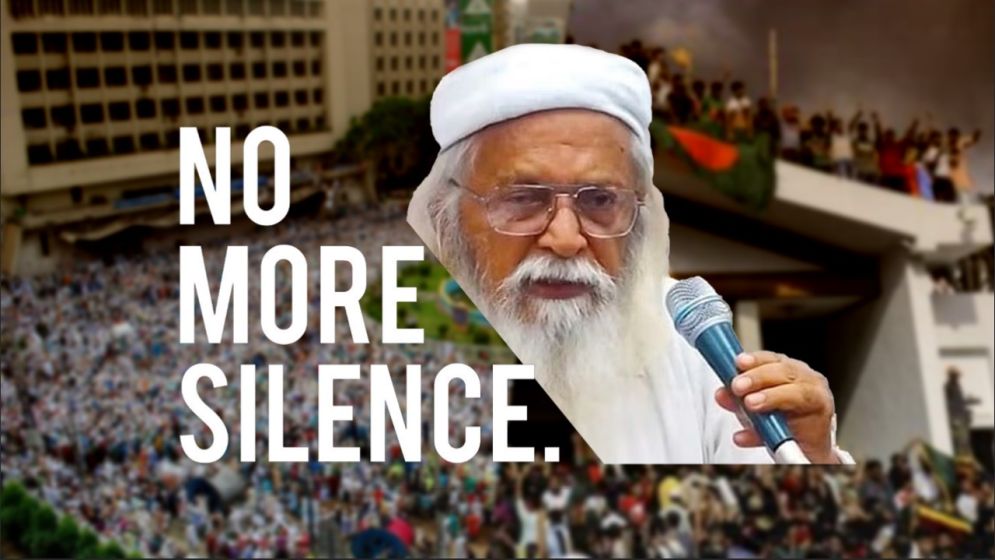

Farhad Mazher always refuses silence…but does his voice still resonate?

In the winter of 2007, when the military slipped into power under the euphemism of a “caretaker government,” a strange quiet blanketed Bangladesh’s political and intellectual elite.

Newspapers that once prided themselves on liberal dissent–Prothom Alo, The Daily Star–pivoted with stunning agility. Under the cover of fighting corruption, they lent their editorial power to a growing campaign to dismantle the very architecture of democratic life.

Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia, the twin poles of Bangladesh’s political landscape, were thrown behind bars. The BNP was splintered by force. Business leaders were dragged into jail cells. The markets tumbled. Prices surged. Fear took hold.

Amid this, public intellectual Farhad Mazhar vanished–from newspaper columns, at least.

His popular pieces, often teetering on the edge of the acceptable, had long made him a thorn in the side of the establishment. But in this climate of state-sanctioned silence, Prothom Alo cut him off entirely.

The intellectual class–so vocal in drawing-room debates–fell eerily mute.

A few of us decided that silence was no longer an option. We organized a public forum at Dhaka University to challenge the new orthodoxy–the military’s creeping control, and the media’s role in enabling it.

Mazhar was there. So was Mahmudur Rahman, later to become editor of Amar Desh. The event was chaotic, almost derailed by some on the left who dredged up the Phulbari issue in an attempt to shut down Rahman. But the meeting continued, defiantly.

It was the first public critique of the so-called “neutral” government–a fragile crack in the wall of fear.

Mahmudur Rahman soon took over Amar Desh and turned it into a rare platform for dissent. While most editors, columnists, and commentators remained cowed into submission, Mazhar and Rahman began a relentless campaign of critique.

The courage it took in those days cannot be overstated. Their words, in black and white, pierced through a nation paralyzed by political uncertainty.

As the military regime cozied up to New Delhi, the full picture became clearer. Tarique Rahman was beaten into exile. Khaleda Zia was pushed to the edge. Media outlets, instructed by invisible hands, began hammering the liberation war narrative like a drumbeat.

The BNP and Jamaat were painted in increasingly binary terms–fundamentalist, anti-liberation, enemies of the state. In the engineered election of 2008, the Awami League coasted to a historic landslide. The military’s redistricting worked as intended.

By 2009, with the mainstream media closed to him, Mazhar began writing for Naya Diganta and Amar Desh. There was no social media back then, no viral tweets, no Facebook lives. If you wanted to be heard, you needed paper and ink.

That Mazhar found refuge in conservative publications infuriated his critics. But those pages printed him without redaction. He never softened his ideas for the sake of palatability.

And here lies the reason Farhad Mazhar remains a problem–not for governments per se, but for the entire apparatus of counter-revolution in Bangladesh. He cannot be absorbed, co-opted, or silenced.

He speaks in a language too erratic for partisanship, too radical for liberal comfort, too defiant for authoritarian tolerance. Whether you agree with him or not is beside the point. The fact that he refuses to be erased is what makes him so dangerous to those who dream of a docile, depoliticized public.

Even today, when many who once claimed radical credentials now echo the narratives of the powerful, Mazhar remains where he has always been–out of step, out of line, and unwilling to fall in.

-6847df3ae931b.png)

Swimming against the

tide

By 2012, any remaining illusions about Sheikh Hasina’s democratic commitments were shattered. With the stroke of a parliamentary vote, the caretaker government system–a hard-won mechanism to ensure electoral neutrality–was abolished.

The message to the opposition was unmistakable: there would be no more fair elections in Bangladesh. Power would now be consolidated, maintained, and renewed under Hasina’s firm grip.

As opposition voices were cornered and the public grew restless over rising corruption, state repression, and administrative decay, protests began building on the streets. The Awami League didn’t respond with reform or dialogue. Instead, it reached for a familiar lever—nationalist hysteria.

The war crimes trials, long dormant, were resurrected and weaponized just in time to shift focus ahead of the contentious 2014 election. Senior leaders of Jamaat-e-Islami were arrested and paraded before tribunals whose verdicts appeared more theatrical than judicial.

The trials served a dual purpose: silencing a key opposition bloc and distracting the public from spiraling misrule.

When Jamaat and its student wing, Shibir, protested, the response was brutal and unambiguous. Police opened fire–no warnings, no crowd control. Just bullets. More than a hundred protesters were killed in a single day, according to even state-aligned media.

The killings were not condemned. Instead, the state and its media surrogates engineered a narrative in which these young men ceased to be citizens with rights. They were labeled “terrorists,” “razakars,” “religious fanatics”--anything to make their deaths politically palatable.

Even the BNP floundered in response. Khaleda Zia spoke up once or twice, but her party, caught between public fear and political expediency, mostly stayed silent.

Then came Shahbag.

On February 5, 2013, just hours after the sentencing of Jamaat leader Abdul Quader Molla, a spontaneous gathering of pro-Awami League bloggers and activists began in Shahbag Square.

Within hours, it became a state-sponsored spectacle. Television channels ran wall-to-wall coverage. Every newspaper fell in line. Within days, what was effectively a pro-government rally was rebranded as a “youth awakening.”

The country’s so-called progressive forces–leftist parties, liberal intellectuals, cultural elites–flocked to the square as if summoned. Suddenly, no one remembered inflation, state violence, or broken institutions. Only the ghosts of 1971 mattered.

India, dispensing with diplomatic decorum, endorsed the movement from its inception. The Shahbagh protests became a proxy theater of legitimacy–not just for the Awami League, but for a broader regional project of ideological control.

When Delwar Hossain Sayeedi’s verdict was announced, mass protests erupted across the country. The government responded with overwhelming force. On that single day alone, over 150 demonstrators were reportedly gunned down.

The message was clear: political dissent, especially if it came from the “wrong” community, would be met with lethal force.

From the start, it was obvious where this was heading. The rhetoric, the violence, the silencing of opposition–it all pointed toward civil war. A handful of us tried to resist this tide.

We condemned the extrajudicial killings. We warned against pitting citizens against one another in the name of history. We called it what it was: a path toward genocide. And then came the killing of blogger Thaba Baba.

He was one of the central online figures of Shahbag, known for his virulently anti-religious writings. When he was murdered in Mirpur, the prime minister immediately declared him Shahbag’s first “martyr” and blamed the Islamists.

But many suspected something else. With social media now widespread, questions emerged quickly–about his identity, his writings, and, most of all, about who stood to gain from his death.

What people found in his online posts–profanities aimed at the Prophet of Islam–sparked a different kind of outrage. When Amar Desh published excerpts, public sentiment turned sharply.

For many ordinary Bangladeshis, this was about a new elite, cloaked in secular virtue, declaring war on their faith.

The slogans at Shahbag had always been aimed at Jamaat-Shibir and “razakars.” But after Thaba Baba’s death, the Islamists seized the moment. They reframed the debate, rallied public anger, and gained political momentum.

The state's attempt to monopolize history had backfired. It had stirred ghosts far more volatile than it anticipated–and awakened a backlash it could no longer control.

-6847df5e72398.png)

Rise of Hefazat-e-Islam

Then, within just three months of the Shahbag spectacle, a very different kind of crowd surged into Dhaka.

On May 5, 2013, millions responded to the call of Hefazat-e-Islam, a coalition of Qawmi madrasa scholars and students. Their rallying cry was simple, but politically explosive: bring to justice those who insulted the Prophet.

For weeks, their demands had been mocked by the mainstream press and ignored by the political elite. But on that day, the capital witnessed a crowd so massive, so disciplined, and so resolute that the state visibly panicked.

By mid-morning, processions from every direction flooded toward Shapla Chattar in Motijheel, the city’s financial center. By noon, the area had become a sea of bodies–peaceful, seated, waiting.

The government, which had grown accustomed to choreographed spectacles like Shahbag, tried to disperse them. Water cannons. Tear gas. Disinformation. Nothing worked.

Even Khaleda Zia saw the writing on the wall. By late afternoon, she instructed her party to join the mass gathering. But the BNP leadership, either paralyzed by fear or mired in internal divisions, failed to act. Had they moved, 2013 might have rewritten the political map of Bangladesh.

Instead, as darkness fell, so did the mask of restraint. In the dead of night, under blackout conditions, security forces launched a coordinated assault on the sleeping protestors. The details of what happened in Shapla Chattar remain murky because the state ensured no footage survived.

Journalists were barred. Mobile networks went down. By morning, the square was empty–washed clean of bodies, blood, and memory. Official figures remain a fiction. But the silence of the grave lingered in the air.

While many turned away, one voice continued to break through the enforced forgetting: Farhad Mazhar. Unlike most of his peers in academia and the media, Mazhar refused to play along with the binary fiction–secular progressives versus irrational Islamists.

He recognized Shahbag for what it was: not a movement for justice, but a state-sponsored rehearsal for authoritarian consensus. And he saw in Hefazat a symptom of deeper fractures the elite refused to acknowledge.

In doing so, he shattered the manufactured consensus.

That defiance made him a pariah. For exposing the moral emptiness of Bangladesh’s self-proclaimed progressives and for standing against the state’s creeping fascism, Mazhar was branded a fundamentalist, a reactionary, a traitor. The hatred he drew was visceral–and lasting.

But the machinery didn’t stop at demonizing dissenters. In a cynical and chilling tactic, the government began orchestrating what can only be called intelligence-driven terror. Bloggers affiliated with Shahbag began turning up dead.

Each time, the narrative was ready before the bodies were cold: Islamists were to blame. No investigation, just declaration. This manufactured fear allowed the state to intensify its crackdown on Hefazat and madrasas.

Overnight, anyone wearing a beard or a skullcap became suspect. Madrasa students were painted as future militants. A climate of paranoia took hold.

And while the public was kept busy scanning for imaginary terrorists, the government got to work on something far more concrete–foreign loans. Mega-projects. Infrastructure schemes wrapped in nationalist rhetoric, but riddled with corruption. Concrete rose where accountability fell. The illusion of development became the regime’s armor.

-6847df7d7219a.png)

Going full-monty on

state-sponsored terror

By the time the 2018 election came around, the state had dispensed with pretense altogether. Ballots were stuffed the night before. Voting day was a formality. Democracy had not just been hollowed out–it had been embalmed.

After the farce of the 2018 election, even some of Sheikh Hasina’s loyal progressive allies began to falter in their convictions. Slowly, they came to the realization that Hasina’s endless invocations of the Liberation War were not about history, justice, or memory—but power.

Her politics of remembrance was a convenient disguise, a mask worn to smother dissent and mask dependency. By then, Bangladesh had effectively become a client state of India, its sovereignty mortgaged for regime survival.

The cracks began to show. The student quota reform protests of 2018 momentarily rattled Hasina’s grip. Young voices demanding fairness in public employment sparked something rare: hope. But it didn’t last.

The protest leaders, once emblems of defiance, faltered after forming their own political outfits. Their moral authority drained away the moment they entered the circus of official politics. Around the same time, the student-led road safety movement ignited across the country with unprecedented popular backing. But again, it was smothered before it could evolve.

Hasina’s regime, seasoned in the dark arts of suppression, deployed its full arsenal: false binaries, weaponized history, captive media, loyalist police, and bureaucrats fattened by corruption. And, of course, a foreign patron eager to keep the regime on life support.

Yet even this manufactured order has limits. In July 2024, the myths began to crack–and then collapse. The people, long suffocated by lies and false choices, rose up in a mass uprising that shattered the narrative architecture the regime had spent over a decade constructing.

The slogans of ‘71 no longer held power. The progressive-versus-fundamentalist dichotomy lost its sting. When the people surged forward, none of Hasina’s borrowed symbols could stop them. The dictatorship fell.

But long before that uprising took form, that one voice of Farhad Mazher always stood apart from the chorus—not echoing it, not flattering it, but warning it.

This is why Mazhar remains so dangerous. Not because he poses a threat to the state with violence or populism, but because he refuses to let the lie hold. He sees through the choreography, speaks the unspeakable, and reminds the nation that beneath all the slogans–liberation, progress, nationalism–there is still blood on the floor.

While most of the opposition was begging Hasina for a "fair election," still entrapped in the illusion that the regime could be reasoned with, Mazhar said plainly what others feared to admit: that the regime was fascist, and that only a mass uprising–not polite negotiation–could end it.

For saying so, he was vilified not only by the regime’s loyalists but also by the very opposition that would later be swept along by the uprising he had long predicted.

After the fall, as the dust began to settle, Mazhar urged the students–the real force behind the revolt–to claim their authority and establish a fully empowered people’s government. He warned against legitimizing the old order by swearing allegiance to a discredited constitution authored under authoritarian rule.

But his vision clashed with the ambitions of entrenched counter-revolutionaries. The old guards reemerged, eager to hijack the revolution they had neither fought for nor believed in.

And now, once again, Farhad Mazhar is their problem. Not because he holds office or commands an army–but because he continues to think, write, and speak without permission.

Because he refuses to submit to the cynicism that so easily corrupts revolutions. Because he still believes the people–not parties, not militaries, not foreign patrons–should be sovereign.

That belief makes him dangerous. It always has. And so, once again, they come for with smears, with threats, with the unhinged desperation of those who fear the truth. They want to bury him. Break him. Silence him. But they forget: they’ve tried before.

Hasina couldn’t silence Farhad Mazhar. And neither will you.

—

Mohammad Romel is a filmmaker and editor