‘New boys in town’ are disrupting Bangladesh’s criminal equilibrium

I stumbled across a Facebook reel the other day, a scene from a Mosharraf Karim drama whose title I can’t recall, but whose premise refuses to leave me.

In it, two muggers, armed with nothing more than a hammer and a knife, stop Karim on the street and strip him of all his cash and valuables.

The punchline isn’t the robbery itself. It’s Karim’s astonishment that the weapon of choice was a hammer– an everyday tool he himself owns at home. He can’t shake the thought: I have a hammer, too. So why am I not out mugging people?

Sometimes, that question stops being a joke. After grinding through marathon shifts, juggling odd jobs, and still falling short of meeting my family’s basic needs, the idea of money–any money, legal or otherwise–takes on a certain grim appeal.

Which leads to the uncomfortable question: those of us who still cling to a work ethic in this country–what exactly is this ethic worth? Why aren’t we all simply thieves?

The short answer: in Bangladesh, even the criminal economy is overcrowded. Thievery is not an open market; it’s a closed shop. You can’t just grab your household hammer and start robbing strangers on the corner.

Not because the police would stop you, but because the existing muggers already have an arrangement with the police–protection fees, bribes, mutual understanding. The real barrier to entry isn’t the law. It’s the old muggers.

Corruption here is an institution. The same logic applies to bribery. You can’t just start pocketing extra cash in your office. You need to negotiate your place within the “ecosystem”--the network of officials who have been perfecting the racket long before you arrived.

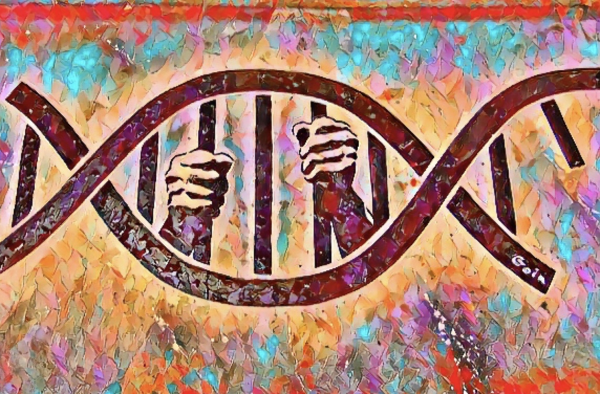

This is because in a country where laws are more performance than practice, a kind of jungle equilibrium emerges–a patron–client system masquerading as functional governance.

The old criminals act as gatekeepers, ensuring that the spoils remain in the hands of an established syndicate. They maintain their “village of thieves” because unregulated plunder would collapse the system entirely.

The result is perverse: a portion of the population remains honest because of the lack of access. The looters live off these honest citizens like parasites, preserving the illusion of “no opportunity” to ensure the survival of their own criminal order.

So, in Bangladesh, integrity is not a choice. It is, for most, simply a failure to get admitted into the guild.

A ‘sustainable’ system of cronyism

The old order of Bangladesh’s underworld relied on a peculiar stabilizer: the idea of “lack of opportunity.”

Crime was the preserve of a select fraternity of seasoned operators. The rest of us–especially the middle-class youth–could rationalize our honesty as the natural outcome of being locked out of that closed shop.

But that equilibrium is breaking. A new generation of young thieves, swindlers, and extortionists–hailing from the very middle and lower-middle-class neighborhoods that once fed the country’s work ethic–are taking matters into their own hands.

They are not inheritors of syndicate power, nor the flamboyant gangster-businessmen like GK Shamim or Zakir Khan, whose wealth was so garish and their political protection so entrenched that no ordinary graduate could imagine replicating their careers.

This new breed comes from hostels and cheap mess halls, from a life of lentils and rice–and within a year, they’re strolling into Gulshan in T-shirts and sandals, walking out with millions in extortion money.

They do not disguise their past; they weaponize it. Their credibility comes from being recognizably ordinary. And that is precisely why they’re dangerous.

When such transformations are visible to every college canteen and tea stall, the message is corrosive: opportunity isn’t scarce–you just have to take it. The moral barrier that kept most young people from imagining themselves as criminals collapses.

Cynicism takes root. Ambition warps. Even those who don’t join political muscle gangs may adopt the same opportunistic adventurism, bending their own positions toward the machinery of graft.

The result will not be a democratization of corruption, but a suffocation of what little breathing space remains outside it.

Entry pressure into the underworld will rise; the delicate “functioning anarchy” that has, perversely, kept the system from imploding will fray. The patchwork order will tear apart faster than the architects of this racket ever intended.

Whether that collapse births a new political order or simply hardens into a more brutal, more inclusive normal for the working class is an open question.

But one thing is certain: when the middle-class youth begin to see crime not as a privilege of the powerful but as a career option for the ordinary, the country’s last moral firewall is gone.

—

Mikail Hossain is a writer and analyst